Catching the Chameleon: 4 Bodies In Barrels, A Mystery Kidnap Victim, A Serial Killer With Multiple Identities & Three Decades of Questions

March 16 2021, Updated 6:01 a.m. ET

October 2018 and Rebekah Heath gasped audibly when she read the message on the screen. She felt like she had been punched in the gut. It was the name that grabbed her attention. Rasmussen. With that one word, an obsession that had gripped her for years finally reached its denouement. Rebecca had discovered the key piece that unlocked a grisly decades-old mystery.

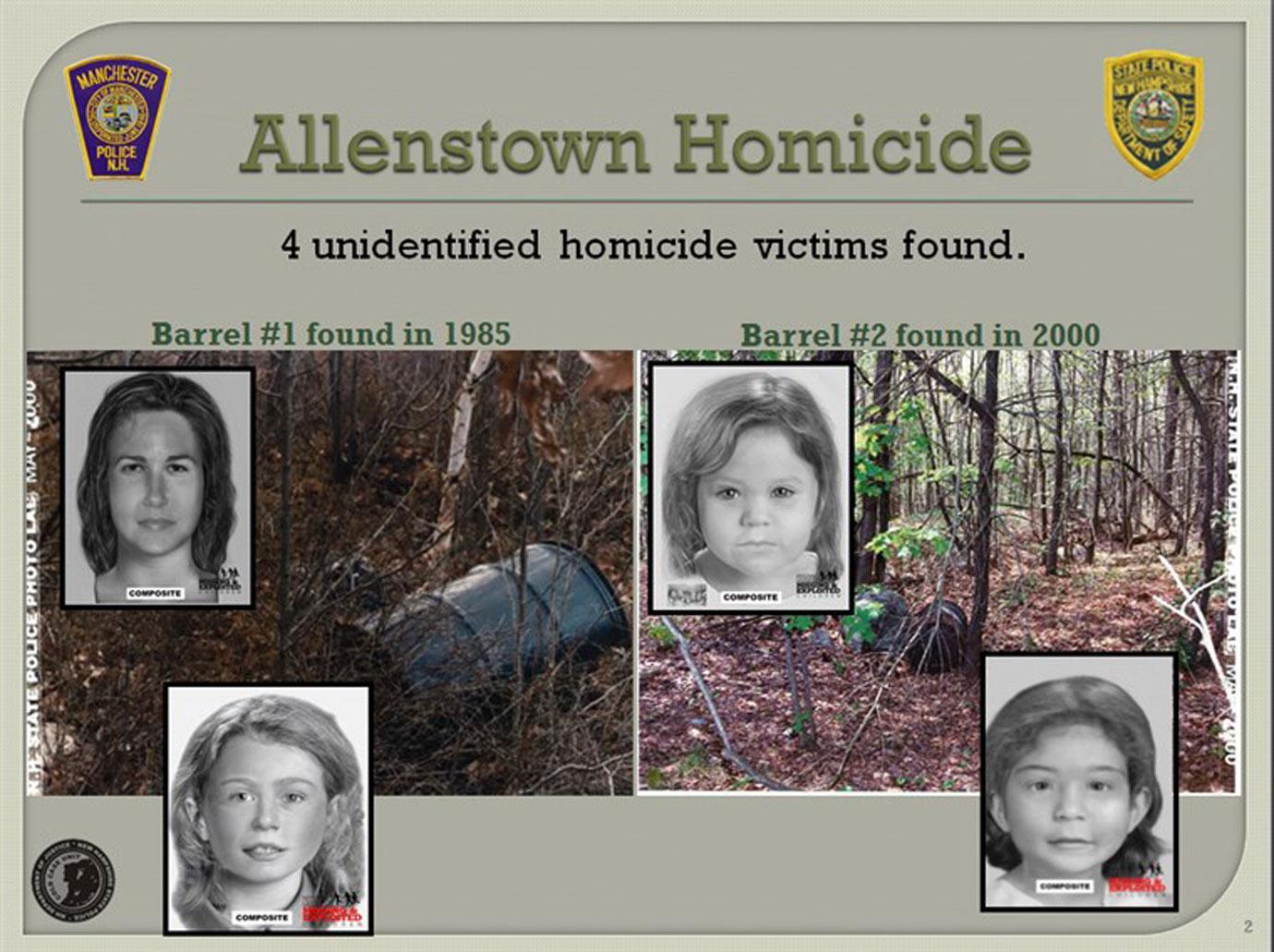

The meticulous librarian, 34, had been on an obsessive quest to find the identities of four murder victims found dumped in two 55-gallon oil drums on the site of an abandoned, burnt-out general store near a trailer park in Allenstown in Bear Brook State Park, N.H. The bodies were discovered two to a barrel, 15 years apart, just yards from each other.

First barrel found in 1985 containing two bodies near Bear Brook State Park in Allenstown, New Hampshire.

In the fall of 1985 two brothers were out hunting when they stumbled across the first drum. One of them noticed a foot protruding from the top of it. He later said he was so traumatized by the discovery that it was 10 years before he was able to go back into the woods.

The drum contained the decomposed, skeletonized remains of a young woman in her early twenties and a girl, aged around eleven. Both had been dismembered and wrapped in plastic sheets.

At the time, New Hampshire did not have its own Medical Examiner’s office, so the remains were flown to Maine. It was assumed the victims were a mother and daughter. By their best estimates, ME's surmised the females had died sometime between 1977 and 1985. Both had been killed by "blunt force" trauma to the head.

Composite sketches were made and released to the media, which reported on the macabre find. The crime scene was searched but offered up no clues. It consisted of the shell of the store, which had burned down in July 1983, and the surrounding area, on which there was a derelict mobile home, camper, and various rusted vehicles, barrels and appliances.

Dark Seas: The 10 Most Horrifying True Crimes Committed On Cruise Ships

Shockingly, it seems likely that cops combing the area missed the second barrel, which was just 100 yards away from the first – although there has since been unfounded speculation that the killer or an associate returned to dump the second set of bodies at a later date.

Composite of the first two victims

Eventually, the first two victims were buried at Saint Jean Baptiste Cemetery in Allenstown. The lead detective in the case organized a graveside service presided over by the town's Catholic priest and a Methodist minister.

The remains were placed together in a steel casket in case evidence arose later and they needed to be exhumed for more tests.

The headstone above the grave read: “Here lies the mortal remains known only to God of a woman age 23-33 and a girl child age 8-10. Their slain bodies were found on November 10, 1985 in Bear Brook State Park. May their souls find peace in God’s loving care.”

The case went cold. People forgot. People moved away.

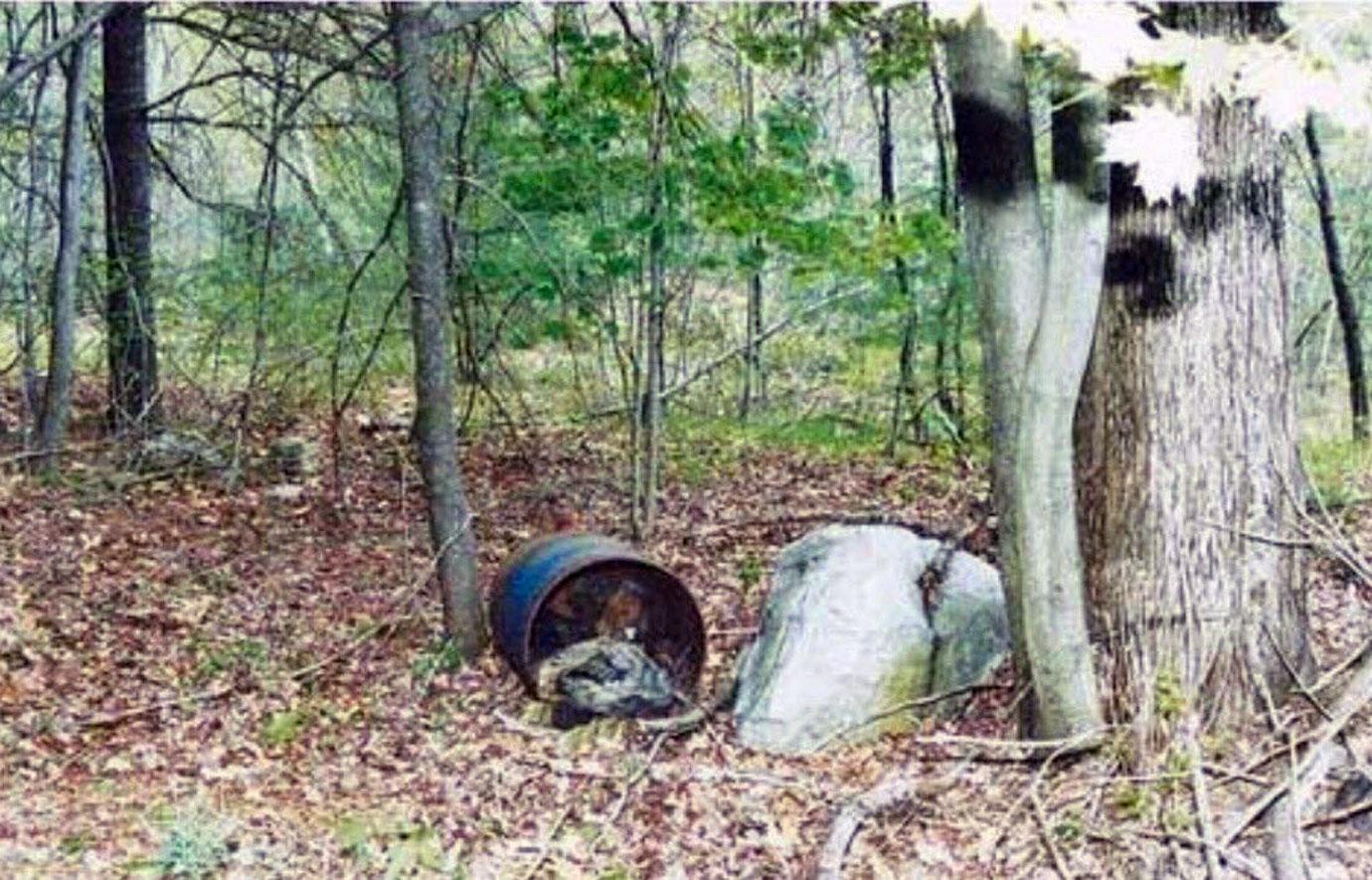

In 1997, town officials planned to clear the Bear Brook Store site and started a survey. An assessment card listed the junk strewn there. It included an "uninhabitable," "vacant" and "vandalized" mobile home, an abandoned, rusty Chrysler four-door sedan, wires, pipes, construction debris and old machines. Chillingly, the report also listed "several 55-gallon drums, some with trash in them."

Three years later, in 2000, the stalled investigation was assigned to a cold case detective and those drums were examined.

One was found to have human legs sticking out of it. It contained the remains of two little girls. As was the case previously, the bodies had been wrapped in plastic sheeting and both victims had died of head injuries.

The girls were estimated to be around two to three years old and a year old, respectively. The 1985 victims were exhumed. In the intervening 15 years, forensic science had evolved and examiners were able to ascertain from DNA taken from all three victims that the adult was related to the oldest and youngest child, but not the middle one.

A second barrel was found in 2000 containing two more bodies near Bear Brook State Park in Allenstown.

Around a decade later, Rebekah Heath recalls reading about the Bear Brook murders in an archived newspaper report. The details immediately aroused her interest. The first bodies had been found three days before she was born, and she was astounded to discover that there had been no resolution.

“It shocked me,” she says. “How could a whole family go missing. It just seemed to me that it was solvable.”

She often scanned old newspapers for unsolved crimes because she had an unorthodox hobby. Rebekah looked for missing girls.

Her modus operandi was always the same. She picked a case, researched it thoroughly and then searched genealogy website message boards dating back decades for posts from people searching for long lost relatives who fitted the profile of her "misper." She created lists of leads and worked through them, checking public records to determine whether people had resurfaced or died. She passed any tidbits she uncovered to police.

Prior to her involvement with the Bear Brook murders, she had never solved a case but found the process engrossing; therapeutic even.

She could easily get lost in research and was driven by deep empathy because, as she explains it, she could have a been a victim herself.

Rebekah grew up in a secluded Bible-believing religious cult. There were round 300 members in the community, which she describes as similar to Mennonites or modern Amish. They refused to name themselves. Rebekah walked out on it when she was 19, cutting all ties to family and everything she had known.

Rebekah Heath at the scene of the Bear Brook State Park

"My interest in Jane Does comes specifically because of my upbringing,” she says.

“When I walked away from the cult and started my life over, I was alone. I look back now and see how completely naive and impressionable I was. I could easily have meet someone who meant me harm without realising it. I could have gone down a path that took me to someone like the guy who killed the Bear Brook victims. I was estranged from my family. I could have disappeared, and no one would have known. It could have been me laying in a morgue without a name.

"At some point searching for the identities of Jane Does became a way for me to process my past. It allowed me to give a voice to the voiceless. I wanted to know why we have so many.

Someone knows who they are, someone has the answers, but who’s looking for them?”

Initially, she was intrigued by the bodies in the barrels case. She often talked about it to work colleagues. Increasingly, her spare time was taken up with research. She did not set out to find the killer. Her aim was to identify the victims. And to do this, she took a step back in the investigative process.

“My starting point was not ‘who are these people,’ it was ‘how do I find the people that are looking for them,' because I figured there must be someone. I tried to put myself in the place of the victim’s family using the scenario that they were not assuming the worst had happened but had just lost touch over the years and wanted to check back in. Where do you go to trace relatives?”

The answer was message boards on genealogy websites such as Ancestry.com and 23andme.

Assassinations, Plane Crashes & Overdoses: Inside The Kennedy Family Curse

Rebekah started compiling lists of posts that fitted the into the right timeframe, location and description of the victims. She explains: “I would scour them night after night and spend hours going through the list of leads I built trying to find records to determine whether the individual identified in the lead was dead, alive or accounted for. I slowly worked through the list crossing off resolved cases. There were hundreds of leads to check.”

In 2017, Rebekah learned two new pieces of information that bought her closer to the true identities of the victims. One came from a true crime podcast released that year, which explained how cutting-edge isotope tests had revealed where the victims had lived.

Isotopes are atoms with either too few or too many neutrons. The isotopes in different regions have different profiles. Geologists use a technique called radio isotope testing to determine details of rock samples based on their environmental isotope profiles. But the technique also offers surprising details about organic life, as plants and animals absorb isotopes through their diet, which are then stored in tissue such as bones, hair and teeth.

Using this technique, scientists were able to ascertain that the related victims – the adult, oldest and youngest child — were raised in and had been living in a swath of territory that covered all of New England and stretched down as far as West Virginia. It also included parts of the upper Midwest and West Coast.

The same tests showed the unrelated child had spent most of her life further inland, and likely further North in two different regions in upstate New York, one on the border between northern Vermont and New Hampshire and one in northern Maine.

She had also spent time in the Midwest and West Coast but was not from the immediate area around Bear Brook State Park.

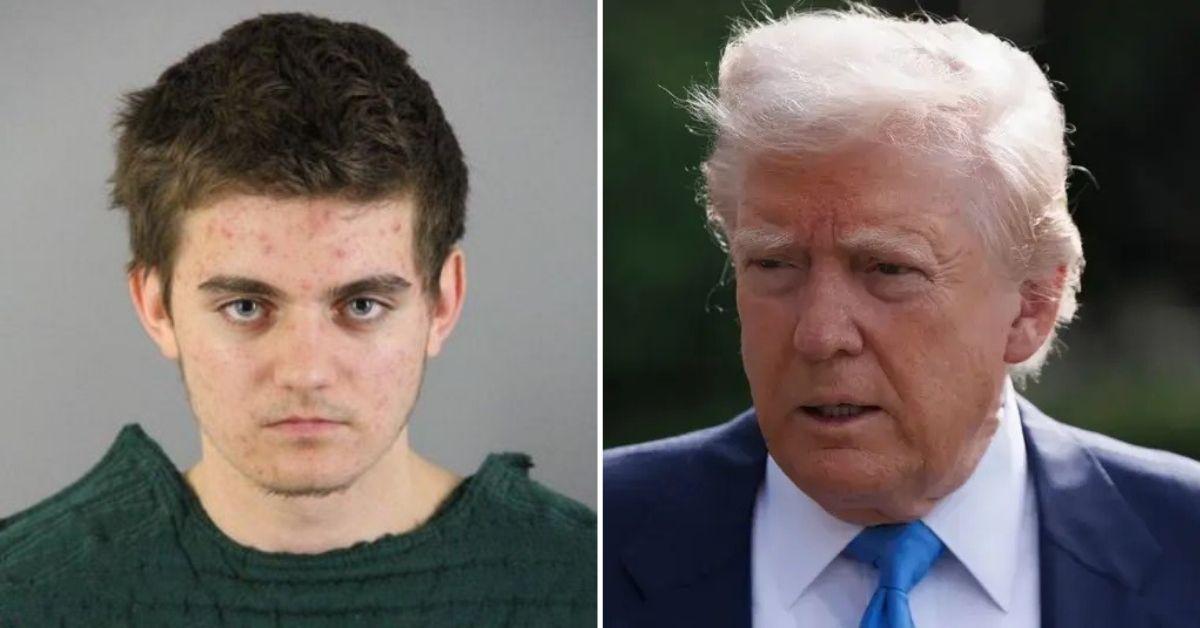

The other vital piece of information was the name of the killer, because in the Bear Brook murder case, cops knew the killer before they knew the identities of his victims. In October 2016, DNA evidence proved that a man who had been jailed for a murder in California and had died in jail in 2010 was the father of the unrelated middle child in the case. He had lived under numerous aliases, and at the time, his true identity was unknown. He had been labeled "The Chameleon."

Terry Rasmussen was arrested in California in 2001 as Curtis Kimball, for killing his common-law wife.

But a year later, in July 2017, he was unmasked, thanks to the pioneering work of another amateur sleuth who discovered his real name was Terry Rasmussen.

Armed with these vital clues, Rebekah revisited a post she’d uncovered earlier in her research.

Serial Killer Showdown! Charles Manson Claimed Greatest Murderer Title Over Ted Bundy

“It was a listing I’d found from a 1999 Ancestry.com message board. It had always stood out. It was from a woman looking for her husband’s half-sister who had disappeared in the late seventies when she was just a toddler. After a year of research, I still couldn’t rule it out,” she explains. “When I heard the podcast, the timeframe and the locations added up.”

Rebekah pulled up the original message from her file. The missing girl was Sarah McWaters. Her mother, Marlyse Honeychurch, had two daughters from two different fathers. Sarah was the youngest, her half-sister Marie Vaughn, was the oldest. No one from Sarah’s paternal family had seen or heard from her since Marlyse left California in 1978 after an argument at a family thanksgiving meal. After so many years, the contact address given on the post was discontinued, so Rebekah used social media to trace the female writer.

Victims Marlyse Honeychurch, Marie Vaughn and Sarah McWaters.

“I sent her a message asking if she was still looking for the girl and she replied within minutes and said yes, she was still looking for Sarah. She sent me more details. Then she mentioned that Marlyse left town in 1978 with a guy. His last name was Rasmussen.”

Rebekah pauses.

“Everything just stopped. That feeling will stay with me for a long time. There they were. Finally, I’d found their identities.”

In that email exchange in October 2018, Rasmussen’s name was the link Rebekah needed to confirm that the family her contact was searching for were three of the victims in the barrels. She went to the police with her findings and they began the process of DNA testing to match Sarah’s living relatives with the remains and so confirm the identities of three of the victims. It took agonizing months.

“By that point, I was in touch with several members of the family and we were all talking, just waiting it out,” she continues. “It seemed to take forever. All the while the family wanted answers: how did he do it, why did he do it?”

To understand that, you need to understand Terry Rasmussen’s chaotic life.

Terry Rasmussen circa late 1950's, early 1960's.

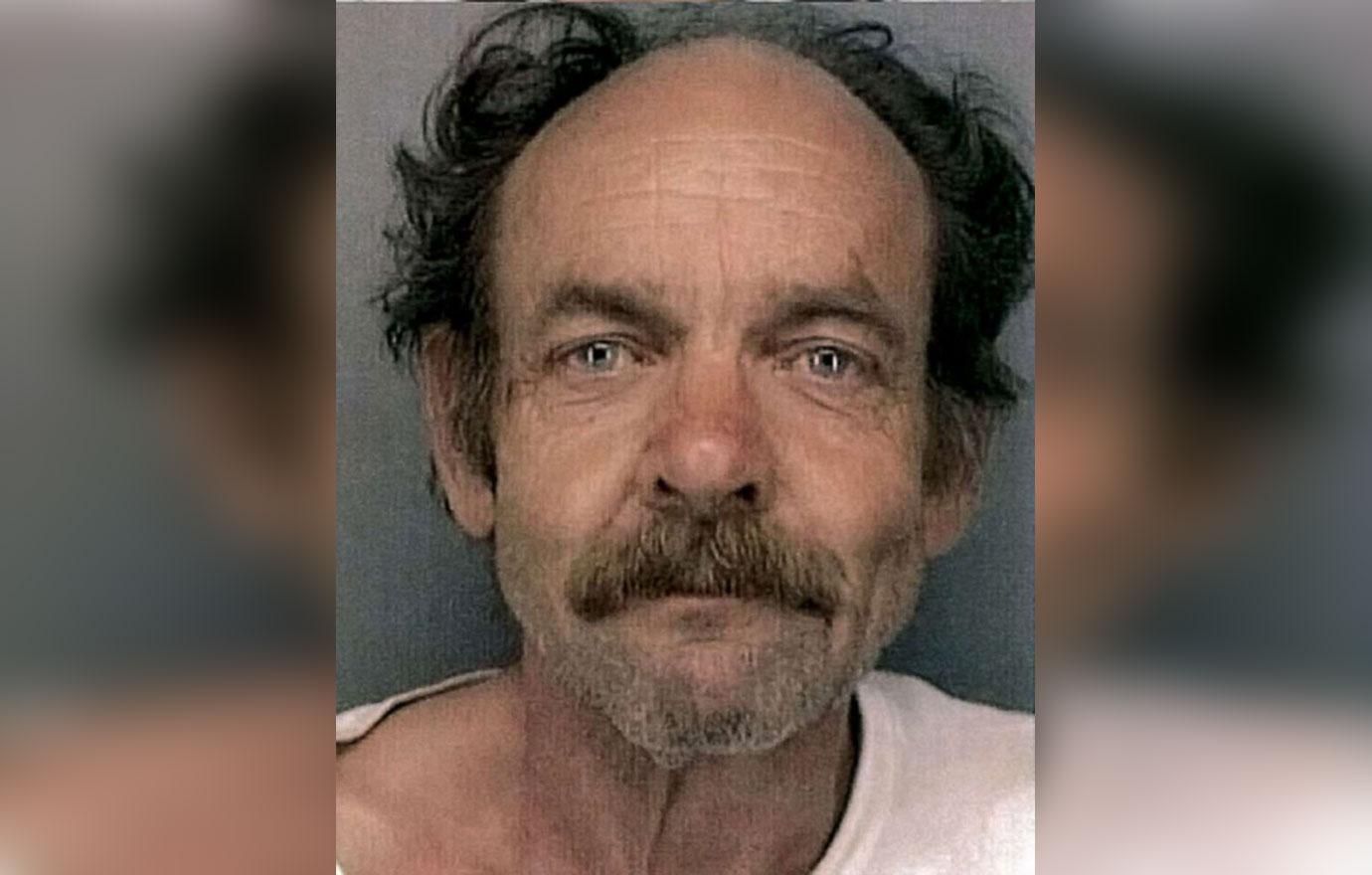

Terry Peder Rasmussen was born in Colorado in 1943. He married in 1968 and had four children with his wife, living in Arizona and California. But in 1975, his wife left him and took their children after Rasmussen was arrested for aggravated assault. Years later his son Eric, a former soldier, recounted how, as a child he was burned with cigarettes by his father – who had a “dead-man” look in his eyes. His daughter Andrea also revealed a family history of addiction and mental illness.

It’s not known how Rasmussen met Marlyse Honeychurch and her two daughters, but in 1978 after the fateful Thanksgiving argument with her mother, the four of them left California and traveled to New Hampshire, where they lived in the town of Manchester and Terry adopted the alias Bob Evans. He worked as an electrician at the general store in Allenstown – where the bodies in the barrels were found – near Bear Brook Gardens trailer park.

Marlyse appears to have been with him for a time in New England and living under the alias Elizabeth, which was her middle name. Documents uncovered later showed she had signed for mail under the name.

It is not known how Rasmussen’s biological daughter fits into this time frame or when she died, but it is assumed Marlyse, Sarah and Marie died after May 1980.

By 1981, Rasmussen, still using his Bob Evans pseudonym, had started dating 23-year-old Denise Beaudin, who had a 6-month-old daughter called Dawn. The mother and daughter disappeared later that year – they were last seen on November 26, 1981, when Denise and Rasmussen went to eat Thanksgiving dinner with her family. As the couple had been having financial problems, her family assumed they had fled town and did not report them as missing.

Denise Beaudin

Although Denise was never seen again, Rasmussen resurfaced in California four years later – under the alias Curtis Kimball – with Dawn, who he now claimed was his own daughter and called Lisa. He was arrested for drunk driving and child endangerment, but after skipping court, abandoned the child with an elderly couple at a trailer park in California where he’d been working.

Lisa – who authorities did not yet know was really Dawn Beaudin – was taken into care. It was not until Rasmussen was arrested for driving a stolen vehicle two years later in 1987 that fingerprints linked him back to Dawn. He received a three-year prison sentence for child abandonment, but when he was paroled the following year, he disappeared again. By this time, Lisa had been adopted.

His movements over the next decade are unknown, but in December 1999, Rasmussen resurfaced in California, using the new alias Larry Vanner. He was in a new relationship with chemist Eunsoon Jun, 42.

Casey Anthony's Parents Facing Foreclosure Again Of Infamous Florida Death Home

When Eunsoon then disappeared in June 2001, police took Rasmussen’s fingerprints – which identified him as Curtis Kimball from the child abandonment case. They searched his home and found Eunsoon’s dismembered body hidden under a large pile of cat litter. Rasmussen was arrested, pleaded guilty to murder and was sentenced to 15 years to life in jail in 2003, still under the name Kimball.

Eunsoon Jun

Authorities then had his DNA tested to discover if Lisa was his biological daughter. But when the tests came back proving she was not, Rasmussen refused to tell detectives who she really was. In 2003, San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department opened a case to find her biological family – but without Rasmussen’s cooperation, it proved fruitless until Detective Peter Headley eventually came up with a new way to solve the puzzle many years later.

In the meantime, Rasmussen lived out his days in jail, still under the name Kimball. He died of lung cancer in 2010, never having faced justice for all the lives he took. Meanwhile in New Hampshire, a decade after the second two victims had been discovered, the Bear Brook murder case had gone cold again. It took another tenacious investigator to breathe new life into it.

Ronda Randall grew up in the Granite State, one hour away from Allenstown. Now living in Maine, she had an interest in online family research and had been informally helping people with adoption research and genealogy for two decades. But by 2011, she was looking for a new challenge and started to research cold cases that she could apply her skill set, too. She knew that, at the time, New Hampshire had no dedicated cold case unit and surmised that the state would be a good place to start, as there was more of a likelihood that she could make an impact.

Ronda, 55, and a mother-of-three grown up children, was a children’s counselor when she first heard about the bodies in the barrels from an old newspaper report. She was surprised that she had never heard of the case and that so little had seemingly been done to solve it.

Knowing the region well, she has her own theories about why the crime faded into obscurity and why there was little effort to publicize it over the years.

“The State Park is a popular leisure area full of beauty and a place for vacations, so maybe they didn’t want to tarnish its reputation,” she speculates. And there is also something about the character of Granite State residents. “Having grown up there I know that people are reticent to talk. They are not curious folk. They mind their own business. They shy away from controversy. I think perhaps people felt uncomfortable about it.”

Brother and sister team, Scott Maxwell and Ronda Randall

The more Ronda thought about the victims, the more she felt compelled to act.

“I wanted to give these girls a voice. There were relatives out there somewhere who didn’t know they were dead.

“As a genealogist, it bothered me that these girls had no identity. The killer had not only taken their lives, he’d stripped them of their identities, and that made me angry. They were skeletonised remains and composite pictures, instead of little girls with real names. It was a robbery.”

Together with her brother, Scott Maxwell, Ronda began a painstaking investigation that spanned almost a decade and became all-consuming.

In the early days, on her first visit the site where the bodies were discovered, she took four stones from the scene, one for each victim, and vowed to one day write their names on them.

The siblings began knocking on doors and asking questions in Allenstown and Bear Brook Gardens. Residents were suspicious. It took time to build trust and one of the most surprising revelations to arise from those early inquiries was that very few people in the area knew there had been four victims.

Ronda continues: “I wanted to get a sense of what was happening in the area at the time and was flabbergasted when hardly anyone we spoke to realized two more bodies had been found in 2000. I had to pull up news reports to show them.”

She played scenarios out in her mind.

“Our assumption in the early days was that an individual had killed this lady and killed the girls and then likely killed himself. We didn’t want to think he was out there, we felt he had come to some kind of end. Family annihilators generally go on to kill themselves.”

Ronda also believed the killer was familiar with the area. She began to trace residents who lived in the trailer park around the time of the murders to build a comprehensive plan who lived where and when on the 155 lots. She scoured official records, searched the internet, pored over registers and formed a Facebook group where 80 former residents helped to re-create a plan of the park. Ronda and Scott investigated each new name and tried to trace them.

Months turned into years and Ronda’s resolve hardened.

“For the first few years I’d wake up wondering about the killer and ask my husband, ‘Do you think he was a child rapist, or a guy who just snapped one day and wiped out his family?’ He would say, 'It’s 2am. Can’t you just go back to sleep’. I became completely consumed. I talked of nothing else. Family and friends became consumed too.

“For a long time the only gifts I wanted at birthdays and Christmas were subscriptions to research sites, archive systems and genealogy databases.”

Ronda and Scott publicized the case to attract more leads.

She flew to Florida to interview the cop in charge of the original case. She flew to Huston to talk to the family of a missing girl she thought might be connected to the case. She turned information over to the police. Cooperation with the authorities varied.

“Some helped and used every tool at their disposal, others kept it all to themselves. The good old boys. We would give them tips and they would never tell us whether they followed them up,” she continues.

She became a constant thorn in the police’s side, making sure the case never went too cold.

And she came tantalisingly close to finding Rasmussen. The siblings interviewed the owner of the General store site several times. He was Ed Gallagher, and initially he was unforthcoming. But having worn him down for several years, in July 2014, he suddenly admitted that he had a suspicion that the person who dumped the bodies was a man who did some work for him in the late seventies and early eighties. His name was Bob Evans (one of Rasmussen’s aliases). Gallagher described him as odd and aloof and said that when asked, he refused to discuss his past. Gallagher confirmed that Evans lived in Manchester and drove a blue VW camper van. He had once been introduced to his pregnant girlfriend.

Overview of the area in Bear Brook State Park and the second barrel, 2000.

“We pursued the lead,” explains Ronda. “I checked for electrician licenses in that name but records didn’t go back that far. We interviewed several people who remembered Evans. One person who had worked with him speculated that he had come from a warmer climate as he wore a winter jacket in New Hampshire year-round. After several months of searching, I turned the theory over to the State Police in December of 2014.”

Jayme Closs' Crime Scene Photos Revealed: Inside Murder-Kidnapping House of Horrors

It was a missed opportunity. Indeed often Ronda felt she was working against the authorities, rather than with them, and still wonders how they could have missed the second barrel for so long.

“To this day my brother and I question whether it was there all that time,” she reveals. “We don’t feel police could have missed it. It was completely visible, not covered by brush. We spoke to a man and who kept pigs there and he couldn’t believe that a barrel with legs sticking out of it would be unnoticed for so many years because his pigs were constantly getting out of their enclosure and would have gone straight to it. It was literally 30 ft from them.

“New Hampshire is a very conservative state, so people don’t change and the whole burgeoning interest in cold cases and true crime didn’t take off there as much as in other areas. Other states made great inroads and used new techniques to solve cases in the time we were involved in the Bear Brook murders, but New Hampshire was slow to move in that direction.”

The years dragged on. Every so often there would be a new tantalizing lead.

In 2012, they flew to Florida to interview the chief officer in the case when the first bodies were first found. He mentioned that all his old case notes might provide clues and that they had been left in a safe in Allenstown police office, but when they inquired, they were told the safe had been removed and there was no record of where the notes had gone.

They discovered a suspect who had a history as a molester and lived in the trailer park. They traced him to an address in Manchester and spoke to a neighbor who said there was a suspicious steel drum buried on the border of their properties. Police were notified. They dug it up but there was nothing in it.

In the course of their work, Ronda and Scott helped solve two other missing persons cases while a third case is still being investigated in Texas.

But the Bear Brook victims were always the focus and, like Rebekah, Ronda’s obsession with the case stemmed from a deeply personal connection.

“In 2007 my niece, Paige, died from leukemia, aged two. We were very close. It made the plight of these unidentified little girls resonate even more. Here were these girls and nobody seemed to be caring for them. It was righteous indignation, compelled in part by our own loss,” she reflects.

So, she kept working on the case. Weekends and evenings. Thankfully, she says, her family was supportive and became as engaged with the case as she was. She attended anniversary memorials for the victims and kept the four blank stones at home as a reminder, unaware that a faltering investigation on the other side of the country, and another genealogist, held the other keys that eventually unlocked the mystery.

In California, cops were still trying to find out who Lisa – the child Rasmussen abandoned — really was. After years of fruitlessly searching a persistent detective Peter Headley theorized a new way to solve the puzzle and, in 2015, contacted Barbara Rae-Venter, a retired attorney who worked as a volunteer "adoption angel," helping adoptees find their birth relatives using genealogy website databases.

Barbara, 72, from Monterrey, Calif., had been retired for 10 years. She was playing a little tennis, traveling and working on her own family history research. In the coursed of that, when she started to get matches from people who were adopted, she started to think about techniques to help them. It was a puzzle, and Barbara liked puzzles.

Genetic genealogist Barbara Rae-Venter

Headley asked her a question. Could the technique she used to trace the biological families of adoptees be used to trace the biological family of someone with no knowledge of who their family was? Theoretically, Barbara replied, yes, it was possible, although Lisa was a complete blank slate and lurking in the background was the possibility that something may have happened to her parents. In a criminal investigation first, Barbara took DNA that Lisa provided and then ran it through popular ancestry websites such as Ancestry.com, 23andme and the aggregate site GEDmatch, to try and find matches.

“It’s a pretty straight forward technique,” she explains. “You take the person who is unknown and find who they share DNA with to figure out who they are. You submit their DNA profile and then you take the people who shares DNA with them and look at how they are related based on the amount of matching DNA. The more matching DNA you have, the more closely they are related.”

While the technique was straight-forward, the task was mammoth, akin to building a vast reverse family tree. At one stage, Barbara identified 94 of Lisa’s distant cousins, all of which then had to be researched to find common links.

“When we hit a brick wall and couldn’t get any further forward with results from databases we had to do target testing, where we asked people we identified to provide a sample that we could then upload and use as a fresh data point to work forward from again,” she explains. “We had enormous numbers of descendants. It was quite the puzzle.”

The project evolved to require 20,000 hours of work and over 100 volunteers, all focused on finding the family of a woman – by now in her twenties – who had been kidnapped by a man who died in jail in 2010.

“It became consuming, you know that the answer is there somewhere. With Lisa we had to do so target testing because we just didn’t have the information. And as it wasn’t known until she was 20 that she had been abducted there had been no press about it, so when police called people and asked if they’d take a DNA test, they Googled it, didn’t see anything and thought it was some kind of scam. Eventually we convinced the San Bernardino Police Department to put out some press releases so there was a record of the kidnapping and the project.”

The system worked. In 2016, Barbara discovered that Lisa was Dawn Baudin, daughter of Denise, from New Hampshire. Along with her team, Barbara traced one of Dawn’s birth grandfathers to the state. He provided the DNA, which proved the biological link and told San Bernardino Investigators that his daughter, Denise, had left town back in 1981 — with a man who called himself Bob Evans. At that point, cops on the Lisa investigation did not know about the link to the Bear Brook case ,but as they liaised with their counterparts in New Hampshire, cops there realized a possible link and arranged to test the DNA taken from Rasmussen (still only know as Kimble) in jail. From that they discovered, he was the father of the middle child. Meanwhile, Barbara used the same technique to reveal his true name – a fact which, when publicized, allowed Rebekah to identify the other three victims.

Barbara’s work was proof of concept for a whole new arm of investigation. The success of her work led to more requests from other police agencies looking to solve cold cases. Her retirement is now on hold and, along with a newly formed team of colleagues, she is working on 50 active cases. Just months after identifying Rasmussen, she used the same genealogy DNA process to help crack the infamous Golden State Killer case. She made Time Magazine’s 100 List in 2019.

Her work has sparked debate about the legality of using genealogy sites for purposes other than family research. Civil liberties and privacy campaigners argue that using DNA data placed on ancestry websites for law enforcement investigation contravenes rights. It is an argument she vehemently rejects.

“We are doing law enforcement or trying to identify someone from remains, suddenly that’s a privacy violation? I don’t see it. It makes no sense. What people don’t understand is that when you upload to GEDmatch you are not uploading your DNA, that stays wherever you tested. You are uploading a text file.”

Initially, for many months, she worked in secret and remained anonymous. The work is not without risks. As the first person involved in this new line of investigation, cops warned her she could potentially be a target for "any wingnut out there who had left his DNA somewhere he shouldn’t have."

The point was bought starkly into focus earlier this year after her work led to the arrest in California of a suspect in a series of brutal rapes. In press briefings the District Attorney’s office revealed that investigative genealogy has been used in the case. Barbara’s name was not mentioned.

At a hearing, the suspect’s lawyer convinced the judge to release his client on bail with an electronic tag. A privacy advocate, who believed Barbara’s work was unethical, posted on Facebook that Barbara had been the person who identified the suspect and revealed that he was in the community under licence. The post compromised Barbara’s safety.

“OK, he was wearing an ankle bracelet, but he was a couple hours drive from where I live. If he decided to pay me a visit, how long would it have been until the authorities realized he’d breached his bail condition?” asks Barbara. “I went ballistic and had the woman pull the thread from Facebook. Her response was, now you know what it’s like to have your privacy violated. It was unbelievable.”

The incident forced Barbara to re-examine her involvement in investigative work. Consequently, she beefed up security on her home.

With so much demand for her services however, she continues to crack cases and has so far solved around 30 crimes. And with the booming popularity of ancestry sites and DNA heraldry services, the process gets increasingly quicker because the dataset has expanded. As a test, Barbara recently reworked the Lisa case using the same methodology. Because there are so many more millions of records uploaded, the process took eight hours, as opposed to 20,000.

“I haven’t been able to get back to tennis yet,” she laughs.

Victims of Terry Rasmussen are remembered, decades after their violent deaths in Bear Brook State Park.

In June last year, after all the DNA tests had been completed, and the names had been confirmed, New Hampshire Police Department convened a press conference to reveal the identities of three known victims in the Bear Brook murder case. There, Ronda met Rebekah met. Poignantly, Ronda asked Rebekah to write the names Marlyse, Sarah and Marie on the stones she’d kept for eight years.

“It was astonishing to finally give those girls their names back,” says Ronda.

Each of the women has been changed by their involvement.

Ronda has forged friendships with many of those involved, including Rasmussen’s children. Rebekah is determined to carry on searching for the identities of nameless victims.

“I didn’t realize how attached I was to the victims,” she says. “They were with me every day. When I did get them identified, it was hard to let them go.”

The answers lead to questions. The identity of the middle child, who Rasmussen fathered, is still a mystery. Attempts to discover who she was and what happened to her mother are ongoing. The fate of Denise Baudin, most likely murdered by Rasmussen, is unknown. Lisa still doesn’t know what happened to her mother. The theory is her body is someplace between N.H. and Texas.

And Rebekah, Ronda and Barbara all agree on one chilling fact. They are sure there are other Chameleon victims buried somewhere, waiting to give up their secrets.