Whacked! America’s Most Gruesome Mob Hits

March 30 2022, Published 4:05 a.m. ET

When a big mob boss falls out of favor, you can be sure of one thing: there will be blood.

Sure, there might be some discussion first, maybe a temporary truce, even a few conciliatory smiles — but in the end, someone ends up in the cemetery. Even some of the most feared characters in organized crime history had their killing careers cut short by a bullet to the head. These “made men” didn’t settle into a peaceful final act in the suburbs with their slippers on, in front of the TV. They died the way they lived — violently. RadarOnline.com profiles some of the most famous hits in history…

Paul Castellano (1985)

“Big Paulie” Castellano was old school. The successor to Carlo Gambino as head of New York’s infamous Gambino family — the biggest Cosa Nostra family in the U.S. at the time — Castellano didn’t believe in dealing drugs, and made it clear that any members of the Gambino family who defied his orders would pay the ultimate price for their disobedience.

But one up-and-coming gangster, John Gotti, wanted in on the narcotics trade. He understood that if he became heavily involved, he’d be demoted at best; more likely, he’d be taken out by his boss’ order, to teach any other potentially rebellious mobsters to toe the line. He also knew that Castellano frowned on his cocky attitude and his $30,000-a-night gambling habit.

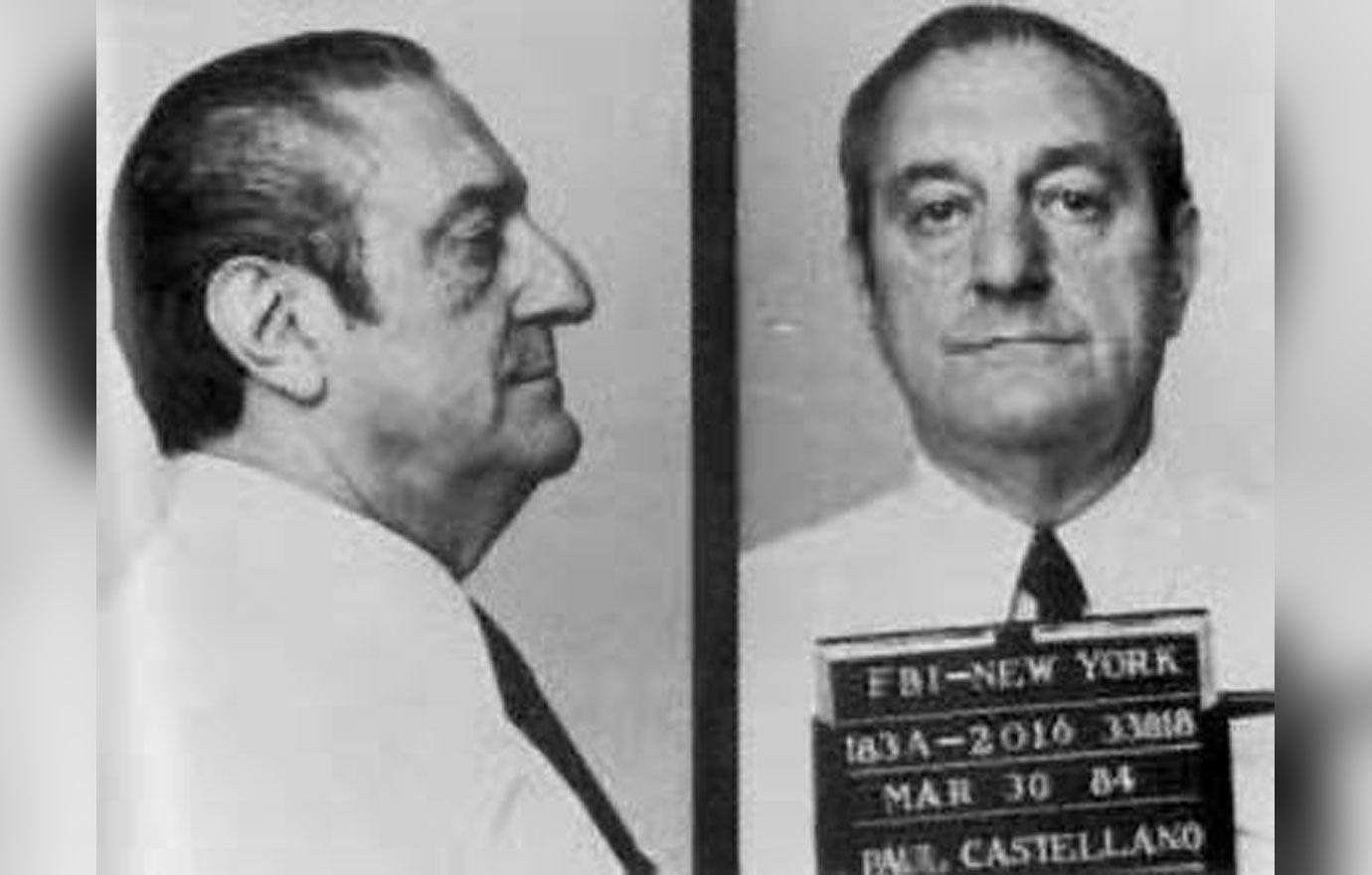

Big Paulie Castellano

So, when Gotti learned that his boss would be meeting with another Gambino leader, Frank DiCicco, at Sparks Steak House in midtown Manhattan on the night of December 16, 1985, he decided to make his move.

As Castellano and his bodyguard, Thomas Bilotti, parked by the restaurant, a team of four shooters hired by Gotti lay in wait. Wearing white trench coats and black Russian hats, they dashed up, guns blazing, as the pair got out of the car.

Castellano was hit in the head, chest and abdomen and died at the scene. Bilotti was also shot dead. Gotti waited in a car just down the street, using a walkie-talkie to communicate with the gunmen. After the execution, he drove up to get a closer look at the blood-spattered bodies. Two weeks later, John Gotti was made boss of the Gambino family.

But the unsanctioned assassination of Castellano sparked years of instability.

Sitting in the car with Gotti on the night of the execution was Sammy “The Bull” Gravano, the murderous enforcer he would make his underboss. During the 1980s, the FBI had tried to convict Gotti on racketeering charges, and each time the mobster had gotten off the hook, earning his “Teflon Don” reputation. But in the early ’90s, Gravano finally gave the government the key to lock John Gotti up.

Facing a slew of charges of his own, Gravano ratted out his old boss, who was finally convicted of murder and a series of other crimes on April 2, 1992. Gotti was sentenced to life behind bars. He died from throat cancer in a prison hospital on June 10, 2002.

Carmine ‘Cigar/Lilo’ Galante (1979)

Bonanno crime family boss Carmine “Cigar” Galante was one of the pioneers of the modern narcotics trafficking business — and it seemed he was intent on keeping the profits for himself.

Coming up on his 70th birthday, he asked the Mafia’s ruling commission for permission to retire; but when they discovered he’d been pocketing most of the drug-dealing proceeds instead of sharing them with the other families, they decided to put him permanently out to pasture.

On July 12, 1979, Galante was having lunch at Joe and Mary’s Italian-American restaurant in Brooklyn when three ski-masked men burst in and opened fire. Galante’s Sicilian bodyguards, Baldassare Amato and Cesare Bonventre, did nothing to protect their boss from the volley of bullets, and were unharmed in the attack that also claimed the lives of the restaurant owner and another Bonanno hoodlum.

Galante, who had an underworld reputation for savagery — he was suspected of being involved in more than 80 murders — was rarely seen without a cigar, or “lilo” in Italian slang. Fittingly, he still had one in his mouth when he died.

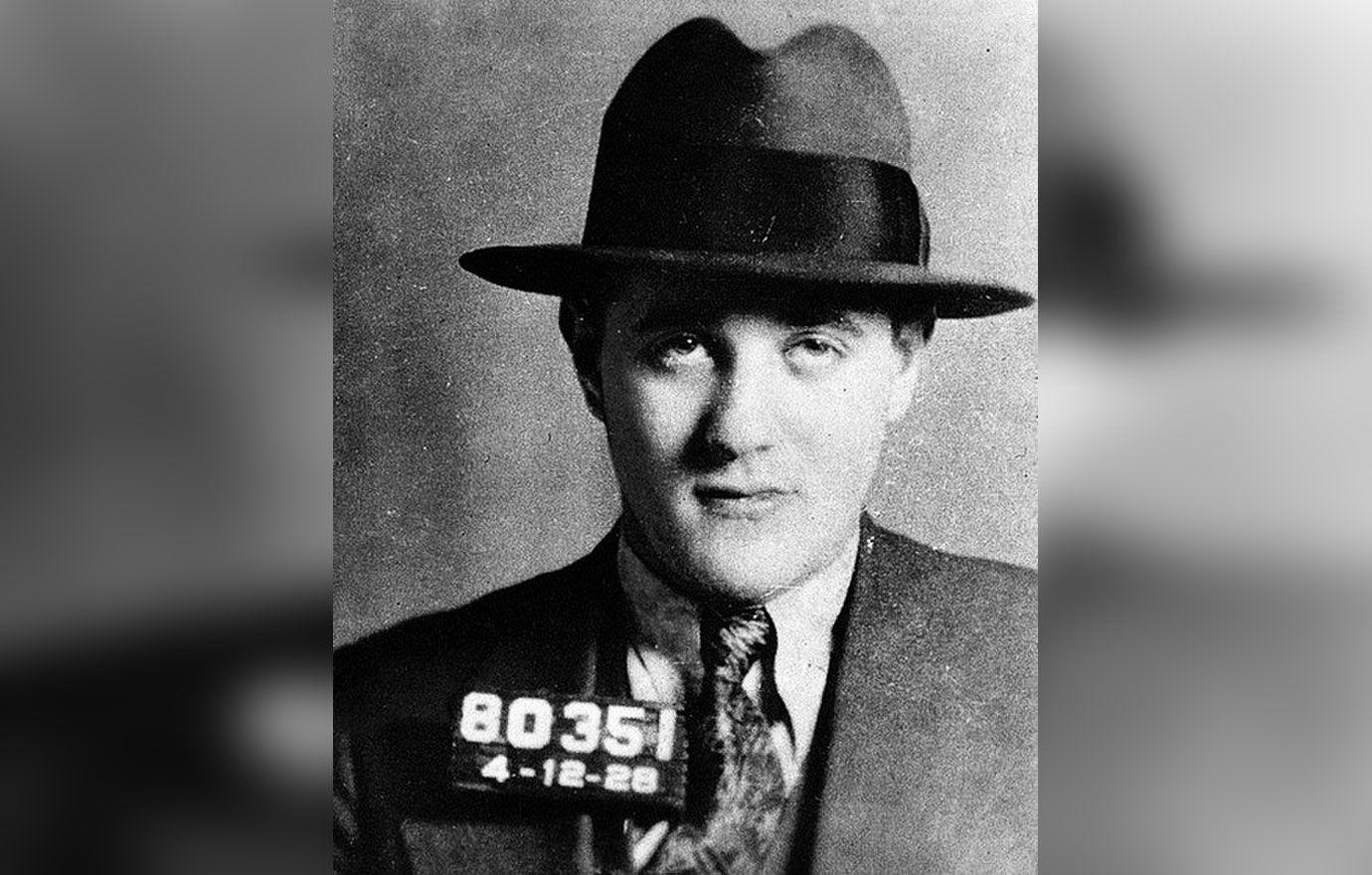

Bugsy Siegel (1947)

Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel wasn’t the kind of shy gangster who pulled strings from a smoky back room. Handsome and charismatic, he was one of the first of the front-page mobsters.

The Jewish-American crime boss was a driving force behind the development of the Las Vegas Strip, and there was little attempt to hide the dealings of the side business he cofounded with mobster Meyer Lansky back in New York: Murder, Incorporated.

From humble roots in crime-ridden Brooklyn, he partied with the rich and famous in Hollywood before meeting a suitably violent and headline-grabbing end in Beverly Hills in 1947.

After Prohibition was repealed in 1933, Siegel redirected his business dealings to gambling and eventually zeroed in on the opportunities of a gaming mecca in the middle of the Nevada desert. The first step was moving to California, where he set up gambling dens and offshore gambling ships while muscling in on the drug, prostitution and bookmaking rackets.

Buying a luxurious Beverly Hills mansion, he lived a flamboyant lifestyle, mingling with movie stars and moguls and dating Virginia Hill, the glamorous former lover of Luciano family capo Joe Adonis.

In 1945, the couple moved to Las Vegas to make Siegel’s gambling dream a reality. When William Wilkerson, the businessman building the Flamingo Hotel on the Vegas Strip, ran short of funds, Siegel seized the opportunity and took over the final stages of construction by using cash from his eastern crime-syndicate connections.

However, when the budget ballooned from $1.5 million to more than $6 million, his fellow gangsters became suspicious, believing — correctly — that Siegel was frittering millions on his extravagant lifestyle.

Among those seething at the betrayal was Siegel’s old partner, Meyer Lansky.

On the night of June 20, 1947, Siegel was sitting reading the Los Angeles Times at his girlfriend’s Beverly Hills home when he was hit by a fusillade of bullets fired through the window.

Nobody was charged with the murder and the crime remains officially unsolved, but Siegel’s theft and mismanagement of the Flamingo is said to have sealed his fate. A meeting of the Mob syndicate that loaned him the funds for the hotel — which included Lansky and Charles “Lucky” Luciano — supposedly agreed on the execution and put a contract on his head.

The day after the hit, three of Lansky’s associates walked into the Flamingo and took control.

Another theory was that Mathew “Moose” Pandza, an associate of Siegel’s Las Vegas partner Moe Sedway, killed him as a preemptive strike. Sedway’s wife, Bee, had reportedly learned that Siegel intended to kill her husband to prevent him from prying into claims he was stealing from the Mob.

The Flamingo may have been the catalyst for Siegel’s demise, but he’ll never be forgotten at the Vegas landmark, which has a plaque honoring him at the casino between the pool and a wedding chapel.

St. Valentine’s Day Massacre (1929)

Al “Scarface” Capone may have been in Florida when seven associates of the rival George “Bugs” Moran’s North Side Mob were machine-gunned in Chicago — but he’ll forever be linked to the most infamous gangland slaying in American history.

Capone himself always managed to stay one step ahead of the law as far as his racketeering was concerned. His downfall, when it came, was because he didn’t pay his taxes.

His swift rise to become the ruthless leader of the Chicago Mafia during the Prohibition era made his name synonymous with organized crime and he amassed a personal fortune estimated at more than $100 million. To cement his status, Capone was always smartly dressed and never armed, but always traveled with two gun-toting body-guards, sitting sandwiched between them in the back when he was in his car.

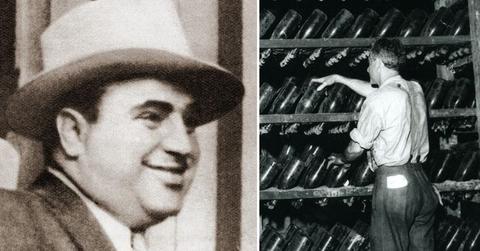

Al Capone

With politicians and the police in his pocket, Capone seemed to be above the law, even after shooting a foe from another gang dead in a Chicago bar.

But if he was able to keep a low profile before the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, his veneer of respectability was tarnished afterward.

At about 10:30 a.m. the morning of February 14, 1929, four of Capone’s henchmen burst into the SMC Cartage Co. garage on the north side of the city, which rival Bugsy Moran used to run his bootlegging operations. Dressed as police officers, the quartet pretended to arrest the seven men, and ordered them to line up against a wall. Then they opened fire. Missing that morning was Capone’s prize, Moran, who’d slept in.

The cold-blooded killings left the public in shock, but with Capone out of town, law enforcement couldn’t prove his involvement and no one was ever tried for the killings.

Still, the authorities went after Capone any way they could. Two years prior, the Supreme Court had ruled that a bootlegger had to pay income tax on his illegal business and the small Special Intelligence Unit of the IRS quickly went after Public Enemy No 1.

In 1931, a federal grand jury returned an indictment against Capone, accusing him of 22 counts of tax evasion totaling about $200,000. Initially, a secret deal was struck with prosecutors to avoid a trial and the risk of witness tampering; in return, Capone’s jail time would be kept to less than five years.

But when the plea deal was revealed there was a public outcry, and it was quickly withdrawn.

A jury found Capone guilty and he was sentenced to 11 years in prison, the maximum term. Three years later, he was moved from prison in Atlanta to the infamous Alcatraz in San Francisco, where his health quickly deteriorated. By the time he was released after nearly seven years, he’d become confused and disorientated from paresis derived from syphilis, and was mentally incapable of rebuilding his gangland empire. He died of a stroke and pneumonia with his loyal wife, Mae, at his side at his Palm Island home on January 25, 1947.