How A Fiat Uno Caused The Crash That Killed Princess Diana 25 Years Ago, According To A New Investigation

Aug. 31 2022, Published 5:30 p.m. ET

The Royals were a House divided even before the fateful events of August 31, 1997; 25 years ago today. A million rumors later, investigative journalist Dylan Howard is calling on Scotland Yard to explore evidence that has led many (including Dodi's father, Mohamed Al Fayed) to suspect the secret that explains their death has been uncovered. Dylan Howard probes the missteps by the French authorities—and uncovers the one man who holds the answer to the greatest conspiracy theory of them all.

Diana, Princess of Wales would have been 61 if she were alive today.

We can only speculate about how that milestone might have been marked or even what the Royal Family would look like today had Diana not tragically died in 1997 – how would she view Charles’ marriage to Camilla? What would her relationship with Meghan be like? Would she have been able to prevent Harry’s split with the rest of the family? – but the fact remains that 25 years after her death, the People’s Princess remains a fascinating figure to millions across the globe.

Most fascinating of all is her death itself. The events leading up to the tragedy, as well as just what caused the speeding car in which she was traveling to fatally lose control and smash into pillar 13 of the Pont de l’Alma tunnel in Paris, remain the subject of fierce debate, conjecture, and conspiracy theories.

In 2019 I conducted a new investigation into her death for my book Diana: Case Solved. Along with a team comprising a former detective, a paparazzo who was in the pack of snappers trailing her every move, journalists, crash scene investigators, forensic experts, and automotive engineers. We pored over every tiny scrap of evidence in a bid to find out what really happened that fateful night.

We retraced all of Diana’s movements while in Paris, we conducted extensive on-the-scene investigations at the Pont de l’Alma, we spoke to scores of people close to the Princess and her team, as well as many eyewitnesses to the accident and aftermath.

We investigated the myriad conspiracy theories – that a chasing paparazzi pack had caused the car to lose control, that she was eliminated by shady international arms dealers, that MI6 killed her after learning she was pregnant with Dodi Fayed’s child, even that Charles had ordered the hit… and ultimately the evidence led us to one inescapable conclusion.

Diana was not killed by international arms dealers, the secret service, or, in fact, by anyone deliberately. Her death was not the direct fault of the paparazzi either. It was rather the end result of a tragic sequence of events nobody could have foreseen, or perhaps even prevented.

My team and I not only proved this – we found the evidence that confirms it.

We also found evidence of another scandal, another conspiracy, entirely… and, most extraordinarily, how a crucial figure in Diana’s death was actually ordered by French police to keep quiet.

So, how did all the myriad Diana conspiracy theories start? And why do they continue to hold traction over 20 years later? The answer lies in two, apparently separate but crucially important, facets of the case.

The first is the sheer incompetence of the French authorities in the immediate aftermath of the crash. The area was not properly sealed off, the scene became contaminated, people were allowed to come and go almost at will, and vital evidence was lost, mislaid, or destroyed – all fuel for those looking to stoke the fires of conspiracy.

In the days and weeks that followed, and perhaps in part due to a kind of panic as the attention of the world focused on the French investigators, things went from bad to grotesque. Witnesses were ignored, or their statements were lost or discounted. We spoke to one American couple whose important eyewitness testimony was taken via a shaky interpreter… and who then were asked to sign their statements in French, which neither of them spoke. Naturally, they refused, and their voices were not heard.

If a police force were deliberately trying to muddle, obfuscate or cover up a crime, this looked very much like how they might go about it.

Unfortunately for the conspiracy theorists, they weren’t trying to do any of those things. The banal truth is the actions of the Parisian authorities were nothing more glamorous or sinister than basic incompetence.

The second important factor in the growth of the Diana conspiracy industry was a little more subtle… and began 21 months before her death.

Diana’s bombshell 1995 interview with Martin Bashir – an interview we now know to have been obtained through deceit – blew her relationship with the royal family apart. Her revelations about Charles’ infidelity, her desperate unhappiness, and – most of all – how the royal household saw her as, in her own words, a “threat of some kind,” was not only sensational television… it instantly and irreversibly made her the biggest news story of the decade.

The Bashir interview created a vicious cycle of paranoia and invaded privacy. It fueled the world’s ravenous obsession with the Princess, which in turn spurred on the paparazzi’s increasingly desperate attempts to satisfy that public lust… which in turn only increased Diana’s belief that someone was out to get her. With every new pap shot, every new headline, the team around Diana became more paranoid… and that paranoia only pushed the voracious snappers to greater lengths in their attempts to get a scoop.

It was all to come to a head in Paris on August 31, 1997.

On the night she died, Diana's fever was at its peak. In the weeks preceding her stay in Paris with boyfriend Dodi Fayed, the press pack had followed her every move, and photographs of the princess were at a premium – get the right shot, at the right time, and you could be looking at a payday worth hundreds of thousands of pounds. The public was desperate for Diana news – and the paparazzi were making a killing giving it to them.

When her Mercedes left the Paris Ritz that night, the shutterbugs were always going to follow – and so they did. But it was not the chasing mopeds that caused the crash. As later inquests revealed, the car’s driver Henri Paul was seriously over the drink-drive limit, with blood tests showing he had a level of 175 milligrams of alcohol per 100 milliliters of blood, compared with the legal limit of 50 milligrams. We confirmed this with witnesses who had seen Paul drinking heavily throughout the night.

Drunk, paranoid, and perhaps keen to impress the most famous woman in the world, Henri Paul floored the accelerator to escape the paparazzi. By the time he reached the tunnel, Paul was speeding so fast that it took the leading photographers on slow-powered motorcycles or mopeds several minutes to catch up to the site of the crash.

Something other than the press pack had played a part in Diana’s death – and the clues lay at the scene of the accident.

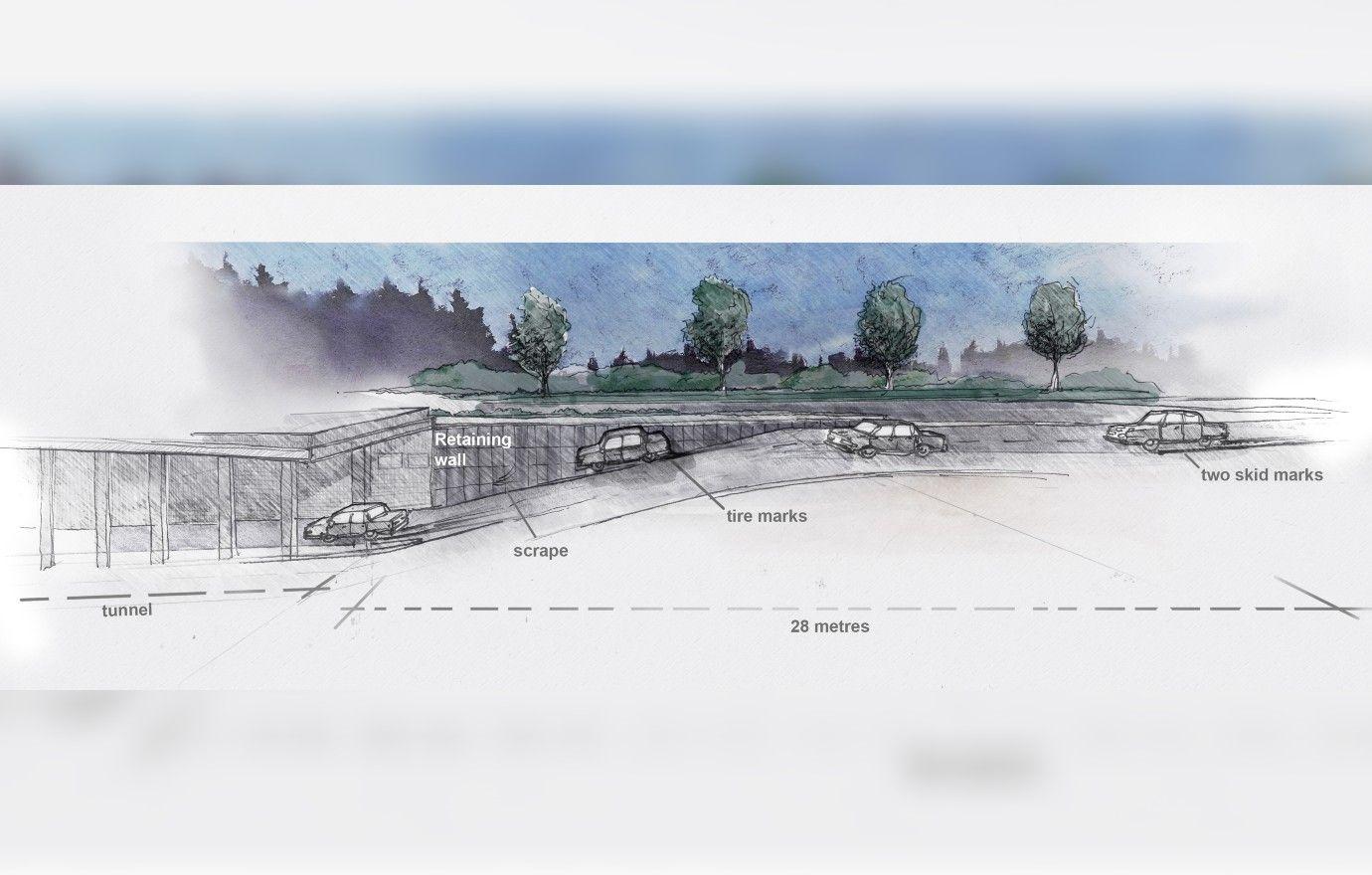

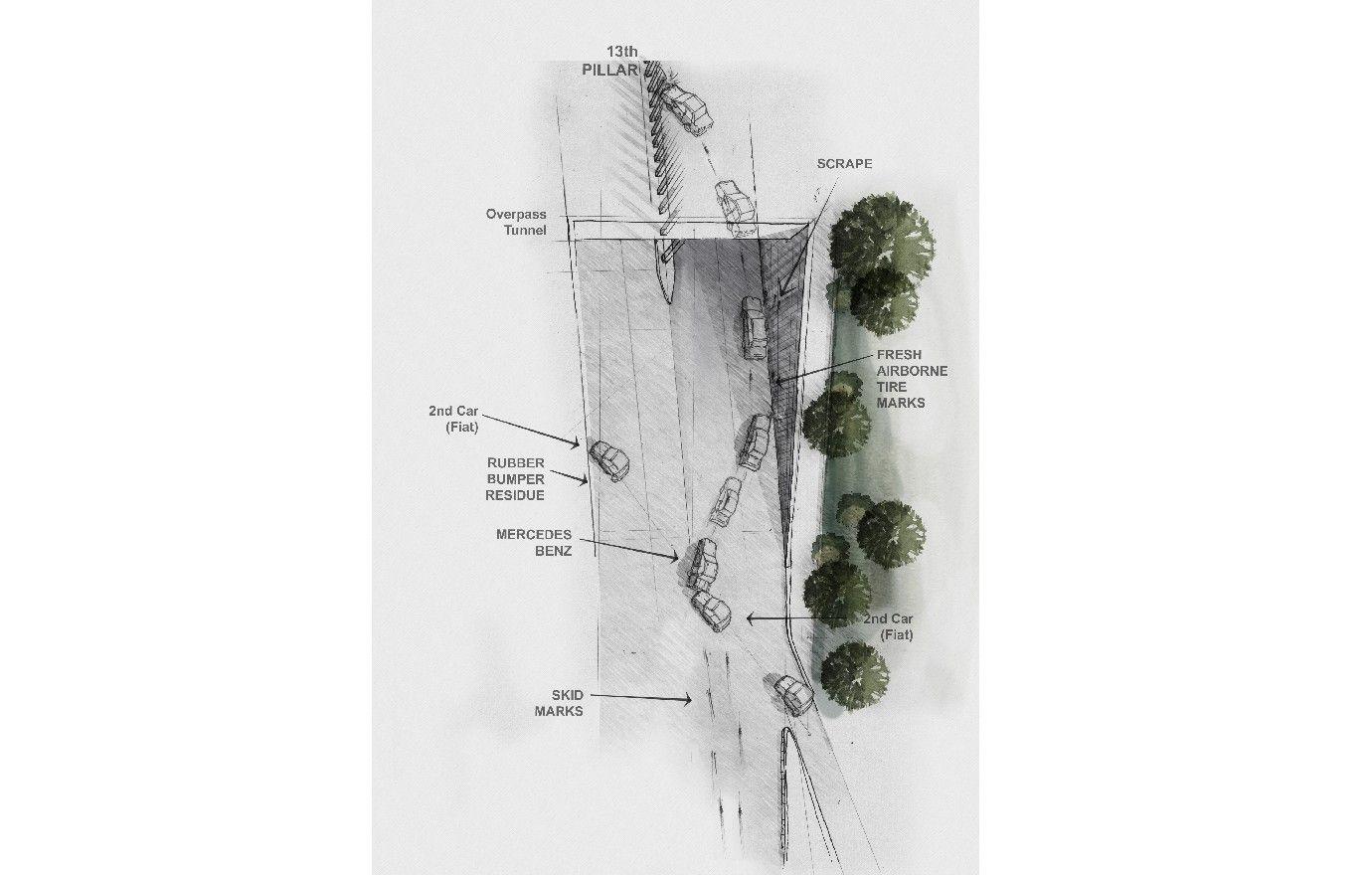

Our investigations at the Pont de l’Alma centered on the old detectives’ mantra: “every contract leaves its trace.” In this instance, it was at several points between the tunnel entrance and the Mercedes’ final resting spot that we found the all-important clues (that still exist today) that would crack the case wide open.

Skid marks where the road dips and veers sharply at the tunnel approach and scrapes and rubber residue — today, they’re still engrained marks — on the retaining wall at the entrance had both been missed by the official investigators – an inexcusable error on their part that could have seen the whole investigation wrapped up within days.

We measured all the markings carefully, took detailed photographs, as well as samples from the residue, and brought all our findings to forensic, automotive, and crash scene experts for analysis. Their inescapable conclusion? Diana’s Mercedes, hurtling along at anything up to 155kph and driven by a man who had consumed the equivalent of a full bottle of wine before getting behind the wheel, had clipped another car coming down the slip road to the tunnel at precisely the point the road veered and dipped.

The impact had sent the car airborne, careering into the retaining wall before smashing into pillar 13 and killing Diana, Dodi, and Henri Paul.

It was nothing more sinister, or more tragically banal, than that. A car traveling too fast, driven by a drunk, receiving a fatal nudge at exactly the wrong moment.

As to who was driving that mysterious second car – and what happened to them… that was another investigation entirely, and one that would see us interview more witnesses the original detectives had overlooked, uncover a hurried respray job conducted in the middle of the night — and end with a confrontation with a man called Le Van Thanh in a quiet Parisian suburb.

What he revealed is perhaps the most extraordinary twist in the whole tragic tale.

An hour outside Paris, I found Le Van Thanh at his home, where his name is on open display at the gate, putting to rest the assumption by Metropolitan Police Commissioner Lord Stevens that the driver would be impossible to find.

The Met was not the only police force that had dismissed Le Van Thanh.

When the initial investigation had looked into reports of a white Fiat Uno seen leaving the tunnel immediately after the crash, the 32-year-old security guard’s name had come up as one of the 4,600 registered owners of such a car in Paris. The most cursory of inquiries into Le Van Thanh was concluded, however, after his Uno was found to be red, not white.

It later turned out that his car had been resprayed, hurriedly (and badly) by his brother, in the hours after Diana’s death.

Le Van Thanh was obviously a major person of interest in the case… but for 25 years he largely has refused to comment. And strangest of all, none of the official investigations seemed to be particularly bothered about this.

I was bothered. My investigation had proved conclusively that the Mercedes had clipped another car at the entrance to the tunnel – and after speaking to more eyewitnesses who not only confirmed the presence of a white Fiat Uno at the scene but positively identified the driver, I was certain Le Van Thanh was our man.

I wanted to find him. I wanted to know why he hadn’t come forward to prove his innocence, and to prove there was nothing he could have done to prevent the Mercedes from clipping his car.

Was there a reason for his reticence, other than not wanting to be known to history? He was not drunk, not speeding, he was just driving home; Diana’s car of course was in the hands of professionals who had made all the errors.

Finally, along with a retired homicide detective, Colin McLaren, we met, in the driveway of Le Van Thanh’s house, shuttered off from the road by huge remote-control-operated steel gates.

If Le Van Thanh was concerned by our presence, he didn’t show it. Friendly, constantly smiling, he told us through our interpreter that he had already spoken to the French police and that they told him “there’s nothing to worry about.” He added that they also knew about his hurried respray job, saying: “The police report, they know why I repainted it. That’s why I let them think what they want.”

As we tried to press him on the details of his movements that night, he became less friendly… but it was after we mentioned the British police that he dropped the bombshell that tied in every aspect of the case.

“You know what the French police told me?” he said. “Don’t go there (to testify in Operation Paget). He said, ‘Not the same law as in France, don’t go there… don’t go there [to England]. It’s the police, which means they don’t agree with each other.'”

It was this comment that floored me. The man whose car had clipped Diana’s speeding Mercedes, leading (albeit accidentally) to the fatal crash, had been explicitly instructed by the French police to not assist the British in their probe into the accident. The French police telling a crucial witness to not assist a lawfully constructed investigation? I was gobsmacked.

And with that Le Van Thanh turned his back, and walked away — never to be heard from since.

Diana’s death was undoubtedly a tragedy, but my investigation has proved it was also an accident. A terrible and freakish combination of factors had come together – her increasing paranoia, the rabid appetite for photographs of her and Dodi, Henri Paul’s drunkenness, and Le Van Thanh’s presence on the slip road to the Pont de l’Alma at precisely the wrong time – to cause her death. There was no conspiracy.

Except perhaps one. The real conspiracy in this tragic tale is the conspiracy of silence. The French authorities have serious questions to answer – about their incompetence, and about their attempts to silence witnesses who might expose the level of that incompetence.

With what we now know, a new inquest should be opened.

Powered by RedCircle