The Best Show Not On TV: Inside The Real-Life 'Succession'—Who Will Take Control Of The Murdoch Media Empire? An Outsider Looms Large.

March 16 2021, Updated 6:09 a.m. ET

The ongoing saga of the Murdoch family empire – unarguably the most far-reaching, influential and powerful media empire in history – has often been more riveting and more outrageous than anything dreamt up in a television writers’ room. From the single-minded ambition of the man who built up a single small Australian newspaper into a continent-spanning corporation, to the swashbuckling, rule-defying, confrontational manner in which he has destroyed any who stood in the way of that ambition, the story of Rupert Murdoch is unique. The closest fictional parallel might be Citizen Kane … though, in typical Murdochian tabloid parlance, that would be “Citizen Kane on acid."

It unfolds like a soap opera. Enormous wealth, vast power, glamorous celebrities, shady politicians, wheeler-dealing, jet-setting … and scandal, intrigue, criminal charges, jealousy, betrayal, backstabbing and bitter feuds.

Rupert Murdoch on the steps of No 1 Aldwych Hotel, in Central London, July 15, 2011. He had been meeting the family of murdered British school girl Milly Dowler inside after the allegations that her phone was hacked for a story in the Murdoch owned News of the World.

Rupert Murdoch has been more than just an extraordinary businessman, he has also been perhaps the single most influential figure in global politics of the last 50 years.

Through newspapers like The Wall Street Journal and the New York Post in the U.S., The Sun, The Times and the Sunday Times in the U.K., and the Daily Telegraph and the Australian in Australia, as well as TV stations including Fox News – and until last year Sky TV, Star TV in Asia, and 21st Century Fox – Murdoch has had a major hand in controlling exactly what news we’re given, how we’re given it … and by extension, what we think of it.

Presidents and Prime Ministers have owed their positions to his endorsement – and their downfalls to his withdrawal of support. Celebrities’ careers have been made and ruined according to his whims. Public opinion on many of the biggest issues around the world, including climate change, the U.K.’s “Brexit” from the European Union, and the scandals faced by Donald Trump, have been directly shaped according to his beliefs and business interests.

He has survived huge scandals, police inquiries, whispers of illegality and accusations by British members of Parliament of running his businesses “like the Mafia,” and not only ridden them out, but come through stronger. As President Trump says, “there’s only one Rupert."

But there remains one fight he cannot win. Now 89 and increasingly frail, the final challenge left for the media magnate is the dilemma common to all emperors: to whom shall he leave the crown?

And so begins the final, and perhaps most enthralling, episode of the Murdoch soap opera – the battle to be named heir. The drama is compounded still further by a new crisis engulfing the empire; a crisis that includes attacks by former heads of state and even open rebellion by one of Rupert’s own children.

That the empire would be passed on to one of his three children, Elisabeth, 52, Lachlan, 48, or James, 47, has always seemed obvious, but the question of which child to favor has become increasingly difficult – and has given rise to tensions, which in recent months have threatened to tear the family apart … not least because of a possible cuckoo in the nest, a pretender to the throne from outside the family altogether.

“Family has always been very important to Rupert Murdoch,” explains media commentator and former editor of the Sunday Times, Andrew Neil. “Particularly from the point of view of forming a dynasty. I remember in the mid-80s having dinner with him one Saturday night after I’d put the Sunday Times to bed and young Lachlan and James were there, I think they were in their early teens and the talk was all then about how he was building a company for them. He used to like to play them off against each other to see how they would survive.”

Rupert Murdoch and his sons Lachlan and James at the Wedding Blessing of Rupert Murdoch and Jerry Hall at St. Brides Church on Fleet Street.

To understand the tension between each of the three pretenders to the crown, you have to understand the history of the Murdoch empire itself. Theirs is a competitiveness which goes beyond sibling rivalry; it is rooted in their separate struggles for identities of their own, outside their father’s long shadow.

“The Murdochs always rally around one other,” says Washington Post investigative reporter Sarah Elllison. “But what divides the children is that they each have their own interest in what they’re all going to get out of this huge inheritance.”

All have worked for the family company in senior positions – in the eyes of some, often parachuted in beyond their experience and abilities – each have faced their own professional, personal and ethical trials, and each have been found – in the eyes of their father at least – wanting.

As he approaches 90 years old, the problem facing Rupert Murdoch is frustratingly simple: none of his children are Rupert Murdoch.

Elisabeth Murdoch attends Red's Hot Women Awards, in London, November 2012.

The Murdoch empire effectively began in 1952, when Rupert’s father, Keith, himself a minor media magnate in Australia, owning a number of regional papers and a radio station, died suddenly of cancer. As the business was broken up to pay creditors and tax bills, 21-year-old Rupert took over the single surviving newspaper, The News, turning it into such a success that he was able to aggressively expand across the country, acquiring a stable of other papers including the popular tabloid the Daily Mirror.

Murdoch’s formula was simple: he increased his papers’ sports and celebrity coverage, he splashed on scandals and high-profile gossip, he pioneered bold, eye-catching headlines in dramatically larger font size than had been used before and he had his editors adopt a tone of witty camaraderie. Reading a Murdoch tabloid was fun – and it made you feel part of a gang.

It worked, too. By the 1970s he had gone international, buying the New York Post, as well as struggling British tabloids The Sun and the News of the World and, by applying the same funny, scandalous, outrageous formula, turned them into the biggest-selling newspapers in the world. He had also branched into “serious” news, snapping up the Daily Telegraph in Australia, and later the Times and Sunday Times in the U.K.

Rupert Murdoch at the auction to bid for the control of the News of the World newspaper group. Murdoch defeated a £34 million offer from Robert Maxwell's Pergamon Press to become the new managing director of his first Fleet Street.

“Mr. Murdoch said that he really didn’t like our European policies, and he wished me to change our European policies,” he said. “And if we couldn’t change our European policies his papers could not and would not support the Conservative government.”

The British premier was clearly astonished by Murdoch’s approach, adding, with typical understatement. “It is not very often someone sits in front of a Prime Minister and says to a Prime Minister, ‘I would like you to change your policy.'"

The aggressive expansion continued – 20th Century Fox and Fox Broadcasting in the U.S., Sky TV in the U.K., the South China Morning Post and Star TV in Asia – as well as numerous regional newspapers, publishing companies and new media startups around the world.

By the turn of the century Rupert Murdoch was indisputably the most successful media magnate the world had ever known, controlling the news agenda across at least three continents. His News Corporation owned over 800 companies in more than 50 countries, with a net worth estimated at anything between $5 billion and $17 billion. In the U.K. alone he published the highest-circulation tabloid and broadsheet newspapers, with The Sun shifting some four million papers a day at its peak and the News of the World the same number on Sundays.

With that success came huge political power. Four million papers sold means some 12 million readers – around a third of the adult British population at that time. Prime Ministers including Tony Blair and David Cameron – both from opposite ends of the political spectrum – queued up to pay homage at the court of King Rupert … and Murdoch himself used that leverage to expand his empire still further.

Another British Prime Minister, John Major, remembered a private meeting with Rupert Murdoch in February 1997, shortly before the General Election.

Major refused to bow to the threat, The Sun duly withdrew its support, declared itself an ally of Major’s opposite number Tony Blair, and three months later the Prime Minister was toast, defeated by a landslide.

Lance Price, a former adviser to Tony Blair during his time as Prime Minister, has said that during Blair’s time at 10 Downing Street, Rupert Murdoch “seemed like the 24th member of the cabinet … His voice was rarely heard (but, then, the same could have been said of many of the other 23), but his presence was always felt. No big decision could ever be made inside No. 10 without taking account of the likely reaction of three men – [Chancellor of the Exchequer] Gordon Brown, [Deputy Prime Minister] John Prescott and Rupert Murdoch. On all the really big decisions, anybody else could safely be ignored.”

It was also during this time that Murdoch began to consider his succession. He had passed the official retirement age of 65 back in 1996, and 2002 marked 50 years since his own father’s death. He was fit and healthy, married to third wife Wendi Deng, 37 years his junior … but he was also under no illusions that he could not work – or live – forever.

Someone was going to have to take over – and with eldest daughter Prudence showing no interest in business, it fell to choosing between the next three: Elisabeth, Lachlan or James.

“Murdoch has always created this sense of ‘family first,' I love my kids, I want all my kids to work with me at the company. That’s always been a dream of his,” says New Yorker journalist Ken Auletta, who profiled the family for the magazine.

“My impressions were that Lachlan has the charming personality that James lacks. James has more bandwidth or brain power than Lachlan … Elisabeth has both charm and brains. I had always heard that she would be the natural person to succeed Rupert Murdoch.”

If Rupert Murdoch’s first love was always newspapers, Elisabeth’s media career has been rooted in television. Rupert first gave her a job as manager of program acquisitions at his California-based cable TV channel FX Networks shortly after she graduated from Vassar College, New York, where she immediately shined. Impressed, he parachuted her into his British satellite network BSkyB in 1996 as general manager, aged just 28. Within a few months, she was promoted again and would take charge of all programming at the station.

“Elisabeth really is such an interesting and smart executive,” says Sarah Ellison. It’s a view shared by Ken Auletta.

“I thought she was the real deal,” he says. “She spotted shows in England and said to her father, ‘You’ve got to put this on in America,' and she made him a lot of money. You could argue in some ways that Elisabeth was the favorite. She would be the natural person to succeed Rupert Murdoch.”

So assured was she at BSkyB, and so promising an heir did she appear, that Murdoch even took her with him to the private meeting with John Major in 1997 in which the Prime Minister’s fate was effectively sealed.

Ironically, it was perhaps this very meeting that sowed the first seed of doubt in Elisabeth’s mind as to whether her father’s empire really was something she wanted to inherit at all. She had seen first hand just how powerful the Murdoch machine could be – and the ethical dilemmas that might follow.

It was a seed that would take root after her marriage to public relations guru Matthew Freud in 2001. Matthew, the son of Liberal MP Sir Clement Freud and great-grandson of psychologist Sigmund Freud, was less than enthusiastic about the political power so freely wielded by his new father-in-law, and often outspoken in his criticism of Murdoch’s motives and means of doing business.

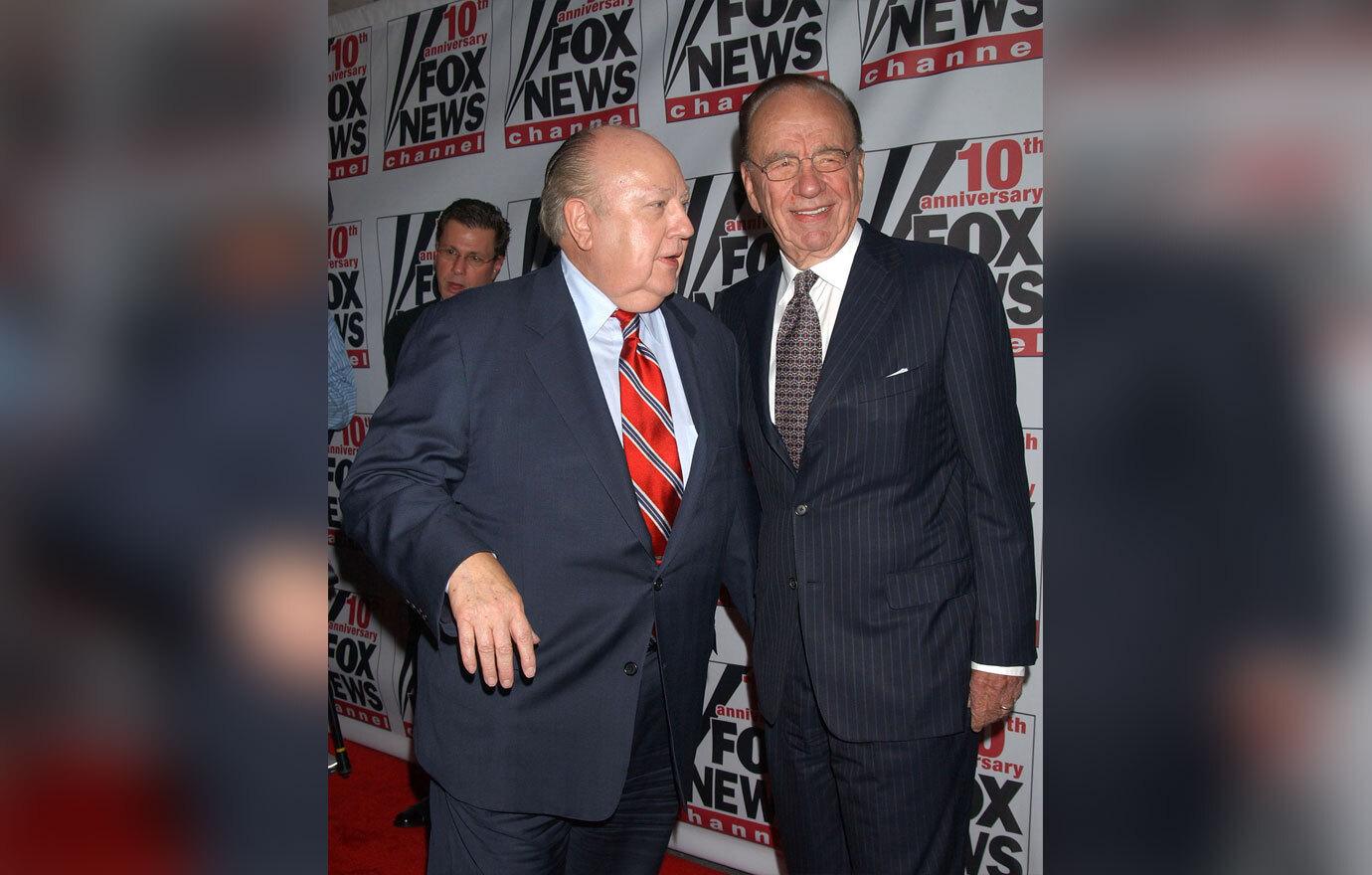

Rupert Murdoch attends the Fox News Channel's 10th Anniversary VIP Party hosted by Rupert Murdoch and Roger Ailes, in New York City 2006.

Gradually, Elisabeth began to distance herself from her birthright. She left BSkyB and formed her own company, Shine TV, in 2001. After selling Shine to her father’s News Corporation in 2011, she is now executive chairman of the critically and commercially acclaimed production company Sister, entirely independent of Murdoch family money or influence. And at 52, divorced from Freud and married to the artist Keith Tyson, she appears to show no desire to return to the family fold.

If, as Sarah Ellison says, “Elisabeth is the child that Rupert has told people is the most like him,” then it’s this very determination to do things her own way would seem to rule her out as successor to her father’s empire.

The same might be true of her brother James – although his succession was never as assured as Elisabeth’s, it was certainly not from want of trying on his father’s part.

After dropping out of Harvard in 1995, James spent the following two decades worked for his father’s companies in a wide range of roles without much in the way of apparent success … and, in some notable instances, abject failure.

His early role as chief of News Corporation’s internet operations included a reported attempt to persuade Murdoch to buy the online news service Pointcast – notable for its pioneering use of “push” technology – for $450 million. Rupert turned down the idea; Pointcast was subsequently sold for just $7 million. He subsequently became chairman and chief executive of Star Television in Asia, at that time losing some $130 million a year, before following his sister to BSkyB, where he was controversially installed as CEO. If Elisabeth had been a clear success at the company, James’ tenure was far shakier.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg of New York, New York, left, and Rupert Murdoch, Chairman and CEO, News Corporation, testify before the United States House of Representatives Subcommittee on Immigration, Citizenship, Refugee, Border Security and International Law hearing on "The Role of Immigration in Strengthening America's Economy" on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C. in 2010.

“Putting James in there when there had to be much better qualified people seemed to me not to send the right signal,” remembers Andrew Neil. “I felt he’d only got it because his name was Murdoch.”

Far worse was to come. In 2011, Murdoch’s British newspaper operation was hit by the worst scandal in media history, when the country’s biggest-selling paper the News of the World was exposed as having illegally hacked into the voicemails of celebrities, politicians, business leaders and even victims of crime – most damningly, including that of murdered schoolgirl Milly Dowler. Not only was the paper forced to close, but a full-scale enquiry into press regulation was launched, and Rupert Murdoch himself summoned to give evidence to the British parliament. For the man who just a decade earlier had so brashly instructed a Prime Minister to change his foreign policy, it was an unprecedented humiliation.

The CEO and Chairman of those newspapers at that time? James Murdoch. Not only had the scandal happened on his watch, but many also felt that he handled the subsequent fallout particularly poorly, with a British Parliamentary report accusing him of “showing wilful ignorance” and “guilty of an astonishing lack of curiosity” over how his businesses were run.

For a man who would be king, it was a near-fatal blow.

“The phone hacking scandal is a real turning point because this is the moment when James loses his footing,” says Sarah Ellison. “Rupert Murdoch sees James’s experience in the U.K. as indicative that James can’t really manage things on his own.”

In recent months James has distanced himself still further, publicly speaking out against his father’s views on climate change, donating to Joe Biden’s presidential campaign, and in July of this year, resigning from the board of directors of News Corp altogether, writing in his resignation letter that the decision was “due to disagreements over certain editorial content published by the Company’s news outlets and certain other strategic decisions.”

In an October 2020 interview in The New York Times, he elaborated still further on the deep divisions between himself and his father.

“I reached the conclusion that you can venerate a contest of ideas, if you will, and we all do and that’s important,” he explained. “But it shouldn’t be in a way that hides agendas. A contest of ideas shouldn’t be used to legitimize disinformation. And I think it’s often taken advantage of. And I think at great news organizations, the mission really should be to introduce fact to disperse doubt – not to sow doubt, to obscure fact, if you will.

Former British Prime Minister Tony Blair (right) and Rupert Murdoch, speak during a news conference held in conjunction with the Atlantic Council's 2008 annual awards dinner in Washington in 2008.

“And I just felt increasingly uncomfortable with my position on the board having some disagreements over how certain decisions are being made. So it was actually not that hard a decision to remove myself and have a kind of cleaner slate.”

Which just leaves Lachlan. Or does it?

Murdoch’s eldest son, the man with “the charming personality,” has at least since the departure of Elisabeth and the failures of James, appeared to be the heir apparent; or as Ken Auletta puts it: “Lachlan is the chosen one. He’s a loyal son.”

Like his father – and uniquely among the siblings – his beginnings at the company were in print: as an 18-year-old he was taken by Rupert to train as a journalist on the Daily Mirror in Australia, and by 23, he was publisher of The Australian.

Although he briefly quit the family firm in 2005 to found his own private investment company, in 2014 – perhaps mindful of the mistakes James had made in his absence – he returned to the fold as non-executive co-chairman of News Corp and 21st Century Fox … and now holds the apparently unequivocally-powerful position of Chairman and CEO of the Fox Corporation.

“Lachlan is someone who wants his father’s approval,” says Sarah Ellison. “He’s spent a lot of time modeling himself after his father.”

So, why the lingering speculation about Rupert Murdoch’s heir? With James out of the picture and Elisabeth apparently keener on building her own empire, surely Lachlan’s succession is unopposed?

That’s certainly how it would seem. But some believe there may be a coup in the works. All of Murdoch’s adult children hold shares in the Family Trust – and with James increasingly vocal about his dissatisfaction with the company’s political stance, and Elisabeth similarly distanced from her father’s views, the theory goes that after Rupert’s death, the siblings could team up against Lachlan to wrest control of the empire from him.

As journalist Maureen Dowd wrote in her October 2020 New York Times interview with James: “Murdoch watchers across media say James is aligned with his sister Elisabeth and his half-sister Prudence, even as he is estranged from his father and brother. When Rupert … finally leaves the stage and his elder children take over, that could make three votes in the family trust against one.”

And as if that wasn’t intriguing enough, there is also a fourth rival for the crown – a woman with all the charm of Lachlan, all the brains of Elisabeth … and all the extraordinary drive and ruthlessness of Rupert himself. Someone who is not even a Murdoch at all.

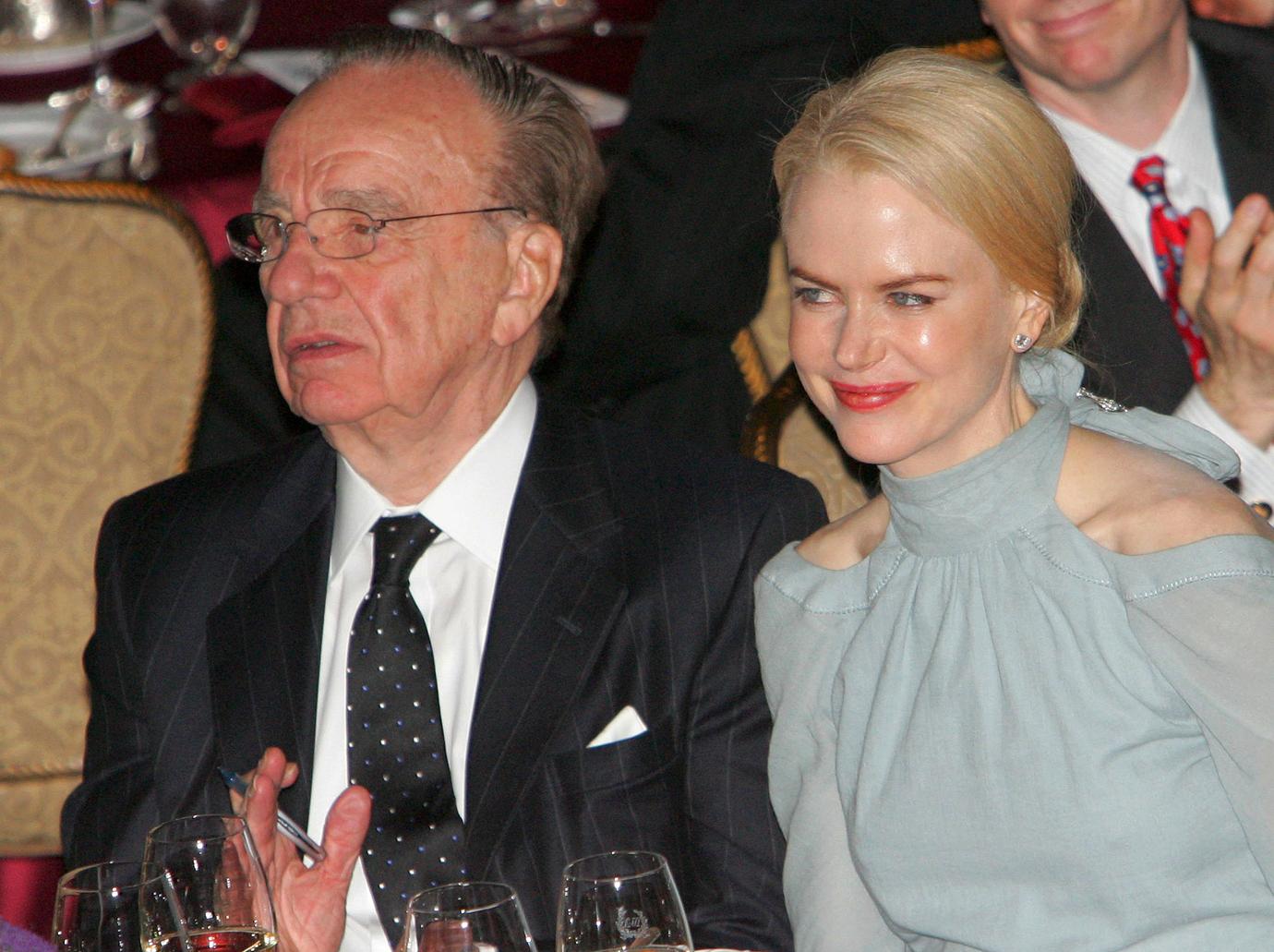

Rupert Murdoch (honoree) and Nicole Kidman attend the Simon Wiesenthal Center's Annual Tribute dinner at the Waldorf Astoria in New York in 2006.

In 2011, as the phone hacking scandal broke, the News of the World folded and the failings of James Murdoch were laid bare, Rupert was asked by a pursuing pack of journalists what his immediate priority was. He gestured to the woman next to him and said simply, “this one."

That woman was Rebekah Brooks, the former chief executive of News International, newly resigned in apparent disgrace, though with a reported $15 million severance package. She had risen through the ranks from secretary at the News of the World to become the paper’s editor aged just 32 – just nine years later Murdoch put her in charge of all his U.K. newspaper operations.

Broadcaster Piers Morgan, who himself edited the News of the World in 1994, describes Brooks as: “a real firebrand. Unbelievably hard working, really ambitious, really driven, and really talented. One of the most talented journalists I’ve ever worked with in my life. And one of the best. But a classic Rupert executive in a way, or the ones that he really likes: funny, sharp, ferociously loyal, very driven and wants to win.”

After Brooks was forced to resign following the phone hacking scandal, Murdoch was as good as his word. Almost immediately following her acquittal of any charges relating to phone hacking in 2014, he reinstalled her as CEO of the company, albeit under its new name, News UK. It was a move that raised eyebrows – and hackles – both in and out of the company … but, typically, Murdoch did not care.

The Australian media mogul at the Commonwealth Jewish Affairs Dinner with Lord Lever.

According to British investigative journalist Nick Davies, whose reports in The Guardian newspaper first exposed the criminality at the News of the World, it is unlikely that remaining as CEO of News U.K. represents the limits of Rebekah Brooks’ ambition.

“Rebekah is an extraordinary person; she is probably the most manipulative person that I’ve come across,” he says. “She’s brilliantly flirtatious with men … and she’s brilliantly flirtatious with women. Everybody thinks that Rebekah is their special friend. Well, that’s everybody who is anybody, everybody who has power.

“I think a lot of people who worked closely with Rebekah say that from an early stage she set out to cultivate Rupert Murdoch.”

Last year, Rupert Murdoch closed what will almost certainly be his final huge business deal, selling a vast proportion of his empire to the Disney Corporation. In a move that was seen as a preparation for his announcing of a successor, it leaves whoever the chosen one might be with a more streamlined operation to manage, comprising mostly of two companies: the Fox Corporation, currently run by Lachlan, for Murdoch’s TV interests, and News Corp, for its newspapers, whose most prominent executive is Rebekah Brooks.

But if this new streamlining was supposed to take a little of the heat off the company in preparation for a smooth transition of power, in Rupert’s homeland at least, the Murdoch empire is once again facing a serious political challenge.

News Corp Australia owns about 70 percent of newspaper circulation in the country, with a total monopoly in some states, as well as TV channel Sky News Australia. And it is drawing increasing criticism for its heavily editorialized stance – on climate change, on the coronavirus pandemic, and on Australian politics.

Influential political magazine Crikey.com.au recently described the corporation as having “evolved into something new, something we don’t have a name for yet, more like a propaganda outlet camouflaged by journalistic practice.” And in October, former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd launched a petition to the federal parliament calling for a royal commission into News Corp’s conduct in Australia and its “overwhelming control” of the print media. Within a few days the petition had gathered more than 280,000 signatures.

“There is a culture of fear in Australia about what happens if you take on the Murdoch monopoly,” Rudd says. “We don’t have press freedom. Murdoch’s journalists are not free journalistic agents. They are tools and a political operation with a fixed ideological and in some cases commercial agenda. We cannot adopt a posture of national learned helplessness and say, well, Australia’s just like that, Australia is just going to have 70 percent Murdoch media domination for ever and a day.”

His views were backed up in November by another former Australian Prime Minister, Malcolm Turnbull, who served until 2018.

“The reality is NewsCorp and Murdoch have done enormous damage to Western democracy,” he said. “In particular to the United States and Australia, and in particular on the subject of global warming. Murdoch media has gone from a news organization that at election times tended to lean more to the right than the left, to become pure propaganda.

“The campaign on climate denial is just staggering. It is so horrifically biased … that Rupert’s own son James can’t stomach it. He is the son of the proprietor and he has walked away and said ‘this is just bias.' James Murdoch was so disgusted he disassociated himself from the family business. Now what does that tell you?”

The Murdoch empire has faced worse setbacks than the wrath of a few former Australian heads of state – but as its supreme leader prepares to step down, it may be that this challenge proves to be the tipping point.

Does Rupert’s oldest son have his father’s powers of intimidation, charm and sheer bloody-mindedness to not only ride out this latest threat to the empire, but, as Rupert has done so many times in the past, emerge on the other side even stronger?

Lachlan may be the obvious choice as heir to the entire Murdoch corporation. But since when has Rupert Murdoch ever done the obvious?

“I’ve always kept in mind very much the legacy of my father and the influence he had on me,” Murdoch told an Australian documentary in 2002. “My father certainly shook up the establishment. And I think I’ve shaken them up over a longer period … and a lot more.”

The Murdochs soap opera is not over just yet. There may still be a twist in the tale, one final unpredictable, buccaneering, establishment-shaking move by the maverick mogul – even from beyond the grave. Stay tuned.