Millionaire Nuns On The Run, Lesbian Trysts & The Wrath Of A Disgraced Bishop

Dec. 6 2021, Published 4:51 p.m. ET

The group of Belgium nuns driving a convoy of luxury cars towards their newly purchased villa in the south of France had broken at least two of the deadly sins, according to the Bishop of Bruges, whose lawyers were in hot pursuit. Their apparent transgressions included greed and envy for the riches their simple life of poverty, austerity and seclusion forbade. Wrath may have also been a factor, as the nuns were angered by the bishop’s decision to starve their convent of new recruits, effectively dooming it to eventual closure. Subsequently, the eight sisters plotted a legal coup and sold the historic 600-year-old building from under the Vatican’s nose.

The Bruges nuns, under the leadership of their Mother Superior, Sister Anna Backx, a spritely 61 at the time, pocketed $1.4m for the building, located in the center of Belgium`s picture-postcard medieval city. With the windfall they purchased a fleet of cars including a $110,000 Mercedes limo, racehorses and a chateau and farm in the foothills of the French Pyrenees near Lourdes. They handed the keys to the convent over to the new buyers and set off for warmer climes in the convoy that also included an ambulance to carry Sister Agnes, 93, who could not see, hear, or walk.

It was 1990, but now, for the first time, using documents and court reports, we can tell the full untold story of the millionaire Belgium nuns and the angry Bishops who tried to stop them. The events play out like a Hollywood movie with subplots that include a forbidden lesbian affair, a tense court drama and a child abuse scandal that rumbles on today.

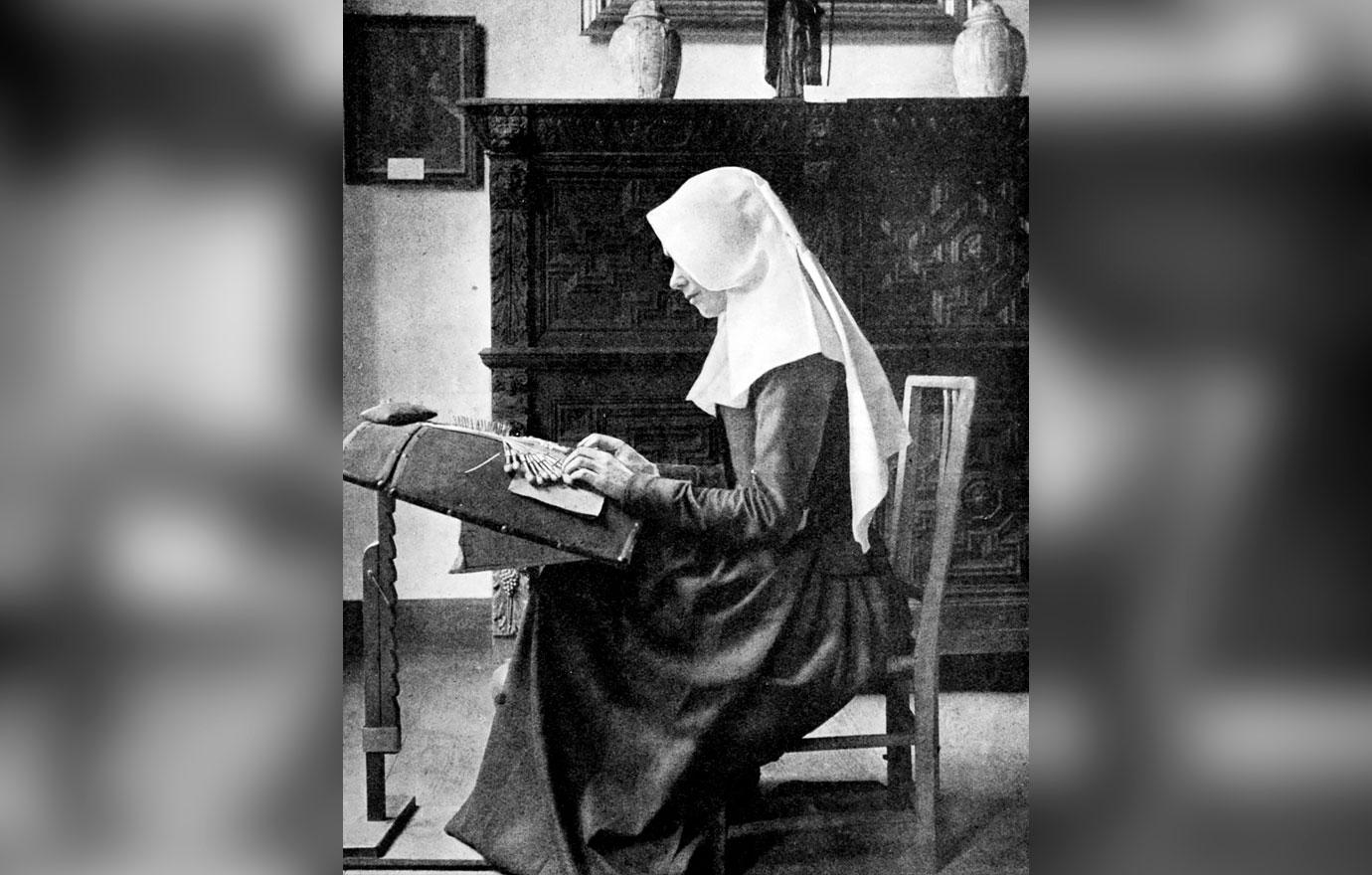

The nuns were from a Catholic order officially called the Order of Saint Clare but generally referred to as the Poor Clares. The order was founded by St Clare of Assisi in 1212. She was the first woman to write a set of monastic guidelines and her house rules were particularly strict, requiring extreme poverty, no property ownership, and total reliance on handouts from the local communities in which her convents were situated.

The Poor Clares

Despite the severe lifestyle required to become a Poor Clare, communities spread quickly throughout Europe. By 1300 there were 47 convents in Spain alone. The Reformation halted the spread of the Order for a time in Northwest Europe but by the 19th Century Poor Clares were in the ascendent again, particularly in Belgium where the nuns based in Bruges and Ghent established another 26 new convents in the country along with a dozen in England, the Netherlands, Germany and France.

But by 1990 the Belgium nun explosion had slowed to a trickle and the once burgeoning Poor Clares of Bruges convent appeared to be in terminal decline. Only eight sisters remained, ranging in age from 61 to 93. According to reports, the catalyst for their actions was the realization that the bishop’s office had placed their home on a list of convents closed to new recruits. With no fresh blood and ageing residents, the designation was effectively a ‘do not resuscitate’ order. When the last nun died, the convent died with her and the property and everything in it returned to the diocese. Church authorities later argued that there were simply not enough young women joining the sisterhood to maintain the convent and that although the inhabitants of the convent were old, they could have lived there for ‘many more years’. The nuns saw it differently. In later testimony, Sister Josephine, described by lawyers as ‘very clear of mind, not senile’ explained the rationale behind what happened next. “Why should we just let it bleed to death and let the diocese get all the goods back?”

A Poor Clares Convent in Belgium

The wily nuns spotted a solution in the arcane statutes that controlled the running of the convent. Under the existing by-laws, the diocese of Bruges stood to receive the property and any goods within it after the death of the sisters. But as the convent was classed as a non-profit organization, the nuns were able to change the by-laws without permission from the Diocese and became its legal owners. They were then free to sell it. They found buyers, a partnership of textile firms, and enlisted the help of a financial advisor named Ronny Crab.

In the subsequent spending spree, with Crab’s help, they bought a chateau in the south of France and a farm, 11 racehorses and six luxury cars including three Mercedes-Benz models equipped with telephones and televisions. As none of them could drive they travelled to their new home in a $110,000 Mercedes limousine. The remaining money was put in accounts.

When news of the scandal reached the Bishop of Bruges, Rev. Roger Vangheluwe, who started legal proceedings to recover the property and any artifacts within it. Reports state that several paintings had also disappeared from the convent, along with the nuns.

Incredibly it wasn’t the only convent controversy the bishop was dealing with at the time. In the coastal town of Nieuwport, 40kms away, another superfluity of Poor Clares, led by their cigar chomping Mercedes-driving Mother Superior, had purchased a disused wing of their convent and turned it into a $100-a-night luxury hotel complete with Persian rugs, antiques, marble bathrooms, a conference center, restaurant and leisure center.

Vangheluwe claimed the sale of the Bruge convent was null and void because the Vatican did not approve it, but legal opinion was divided. At the behest of the church, police launched an investigation, and a complaint was made against Crab, who was accused of assaulting a novice nun, forgery, fraud and breach of confidence. He was arrested on February 27, 1990, while investigators were dispatched to France to question the nuns. In Bruges cops seized historic artifacts from the convent that the nuns had left behind.

Rev. Roger Vangheluwe

Despite testimony from the nuns that they were aware of what they were doing, Crab was thrown to the wolves and stood trial in March 1990 accused of swindling the nuns through abuse of trust to gain control of their financial affairs. He was found guilty and jailed for 39 days before an appeals court released him. Outside the jail in Ghent, his lawyer, Clive Van Aerden, explained to reporters that it was a ‘trumped up case all along’ and that the church had leant on the police to launch a criminal case to justify a civil claim to recover the goods.

A spokesman for the bishop denied the accusation.

“The church has never wanted the goods of that convent,” he said. “The bishop was only interested in the welfare of the sisters.”

Van Aerden explained to reporters that the nuns wanted the proceeds from the convent to go to their families rather than the church after they all died, so they changed the statutes of the convent. He told reporters that he’d read a deposition given in the south of France by Sister Josephine in which she told the police that she knew her convent ‘was on a list where the bishop didn't allow any new nuns to come in’ and didn’t want it to go back to the diocese after the sisters had died.

The lawyer added that as the convent's old bylaws prohibited all luxuries, Crab was happy to teach the nuns how to live a new luxury lifestyle.

When asked why they’d bought six flashy cars when none of them could drive he shrugged and replied: “They wanted them, so they bought them. It's as simple as that. That's why this whole inquiry is so silly.”

But that wasn’t the end of the story for both Crab and his religious clients. Legal claims continued. The nun’s bank accounts were frozen by court order and without funds they were forced to sell their French villa less than a year after moving there. They returned to Belgium in November 1990, where they purchased a villa in Kappellen, near Antwerp. Meanwhile the criminal courts continued to pursue Crab. In May 1993 he was summoned on charges of breach of trust for a sum of 46.000 francs (around $1350) and assault and battery. A month later the charges were increased to forgery and use of forgery, fraud for 10M francs (around $294,000), assault and battery and breach of trust. His trial started in February 1995 when the prosecution claimed that Crab had got rich at the expense of the nuns and assaulted a sister. The court heard that in the intervening years Crab had written a book about his life in the convent and sold the rights to shoot a movie.

In April, Bruges Criminal Court, chaired by Ms. Sabine Ongenae, acquitted Crab on the charge of breach of trust and accepted that the extravagant purchases were made with the full consent of the nuns. The court ruled that Crab had no power of attorney and threw out the accusations of forgery and use of forgery.

Crab’s vindication was only partial however, as the assault and battery charge was upheld and he was sentenced to a suspended six months jail sentence and fined 12,000 francs.

Determined to clear his name Crab fought on, protesting his innocence. He claimed that he’d been made a scapegoat for the nuns and that he was being victimised by the church. He appealed against the conviction and over a year later, in June 1996, Ghent Court of Appeal acquitted him of all charges. In what must have seemed like divine justice to the man who had, by then, spent six years being pursued by the courts and who had apparently been hung out to dry by the sisters he helped, the nuns were ordered to pay his legal costs of 700,000 francs (approx. $20,500).

Crab was jubilant and announced that he would be seeking compensation from the state for false imprisonment and from the Bruge nuns for money he claimed they owed him.

“I don't want revenge, that's a bad word,” he said. “But that won't stop me from claiming damages from the state for my 40 days of unjust preventive detention.”

In an emotional interview he attacked the church and the Bishop of Bruges in particular.

“From the outset, the case against me was based on a string of lies,” he explained. “Everywhere else in Belgium, the Church wanted to bleed the community, in order to grab its goods, a tactic that did not work with the nuns. It was then that the clergy attacked me.

“It was the sisters who wanted a flotilla of luxury cars, it was they who wanted a farmhouse and it was again they who decided to sell the convent of Bruges and buy a castle in Pessan, in the Pyrenees. All of this was in line with their ambition as liberated women from the grip of the Bishop of Bruges. When the business turned sour for the sisters, and the Bruges prosecutor's office, influenced by the bishop, decided to block the nuns' money, they simply wanted to crucify me.”

He then made sensational claims about a lesbian love triangle within the convent. Crab told stunned reporters that the fraud allegations had been cooked up by a nun, Sister Clara, who had been jilted by the Mother Superior, Sister Anna Backx. According to Crab, jealous Clara had gone to the Bishop, and accused her former lover of mismanagement of the convent.

He said: “Anna left Clara for another friend. Seeing her dreams fade away, Sister Clara insinuated that Abbess Anna Backx had mismanaged the convent and that there was even a question of fraud.”

Crab’s dramatic absolution after years of legal wrangling, was equal to the divine justice that appears to have been meted out to his adversaries; Rev. Roger Vangheluwe and the Poor Clares of Bruges.

In their new home, and with their living expenses under control of the church again, the nuns were effectively prisoners, according to Crab. Worse still, they had to accept a representative of the bishop on the board of trustees of their new home, who Crab implied was a spy for the authorities placed there to keep them in line.

“It is their Trojan horse,” he explained.

The nuns appear to have lived out their lives peacefully but the same could not be said for their nemesis, the Bishop of Bruges.

In 2010, then aged 73, Roger Vangheluwe became the first European bishop to resign due to child abuse allegations. In a scandal that rocked the Catholic church in Europe, it transpired that Belgium’s longest-serving prelate had abused his own nephew over a period of 13 years. He was forced to resign when a friend of the victim threatened to make the abuse public. Vangheluwe acknowledged molesting “a boy in my close entourage.”

As the case unfolded it became evident that church officials had been warned about Vangheluwe’s abuse 25 years previously but had taken no action and attempted to cover up the scandal. One retired priest, Rev. Rik Devillé, said he had tried to warn Belgium’s cardinal, Godfried Danneels, about the abuse in 1996, the year Crab was cleared, but was berated for doing so.

Godfried Danneels

The Archbishop of Brussels made a public statement that Vangheluwe’s resignation marked an end to cover-ups. Within two months more than 500 people, mostly men, claimed they had been abused.

Shortly after Danneels retired in 2010 a secretly taped conversation was leaked in which he was heard urging Vangheluwe’s victim to say nothing about the abuse until after his uncle could retire. Danneels told the victim: “The bishop will resign next year, so actually it would be better for you to wait. I don’t think you’d do yourself or him a favor by shouting this from the rooftops.”

The cardinal was then heard warning the man against trying to blackmail the church and suggested that he accept a private apology from the bishop and not drag ‘his name through the mud’.

The victim responded, “He has dragged my whole life through the mud, from five until 18 years old. Why do you feel sorry for him and not for me?”

Cops raided the church’s Belgian headquarters and drilled into a cardinal’s crypt and confiscated computers and documents, searching for proof that the church had concealed evidence. Pope Benedict XVI called the police action ‘deplorable’.

Vangheluwe, meanwhile, retreated to a Trappist monastery. Under Belgian law at the time, a sexual abuse victim could only lodge a criminal complaint up to 10 years after turning 18. The victim in the Vangheluwe case was 40. Vangheluwe escaped prosecution because the case was too old.

In a sickening TV interview in 2011, Vangheluwe denied being a paedophile and called his crime “a little bit of intimacy’. He then admitted to molesting a second nephew.

“As in all families when they came to visit, my nephews would stay over. It began as a kind of game with this boy. It was never a question of rape, or physical violence. He never saw me naked and there was no penetration. I don’t in the slightest have any sense I am a pedophile. I don’t get the impression my nephew was opposed, quite the contrary. I knew it wasn’t good. I confessed it several times,” he explained.

Meanwhile, 24 Belgian, French and Dutch nationals who alleged to have been sexually abused by Catholic priests when they were children filed a class action demanded €10,000 in compensation from the Holy See and several leaders of the Belgian Catholic Church and various Catholic associations.

In October 2013 the Ghent Court of First Instance ruled that the Church could not be sued as it had the same immunity as any recognized state. In February 2016 the Ghent Court of Appeal upheld the judgment.

Following the ruling the victims lodged an application with the European Court of Human Rights in February 2017. They argued that by applying the immunity principle, they had been prevented from pursuing their civil claims, in violation of the European Convention on Human Rights.

In October this year the European Court of Human Rights upheld the Belgium court’s decision.

The catholic church, it appears, is legally untouchable.