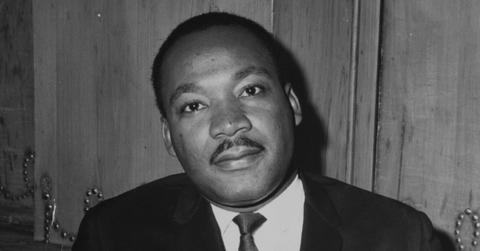

The Killing Of Martin Luther King: The Civil Rights Leader’s Last Days, James Earl Ray & The Conspiracy Exposed!

A 1999 civil jury concluded MLK's death was the result of government involvement and several others.

Jan. 17 2022, Published 8:21 p.m. ET

Martin Luther King Jr. had an eerie premonition about his death. After the Nov. 22, 1963, assassination of President John F. Kennedy, a worried King told his wife, Coretta, “This is what is going to happen to me also.” He’d had that same ominous feeling many times over the years.

As the leader of the civil rights movement, King received death threats almost daily. His powerful oratory carried by television and radio airwaves galvanized the nation, inspiring both Blacks and whites. But there were many who hated him and everything he stood for — primarily white supremacists violently determined to prevent integration.

Radical Black activists who wanted “change by any means necessary” also condemned King’s nonviolent approach as “criminal.” They strongly believed that his policies would prove futile and that the answer to injustice was revolution — in the vernacular of the time, “Burn, baby, burn!”

When he publicly condemned the Vietnam War, King also lost supporters who feared he’d alienate the very politicians whose help the movement needed, especially President Lyndon Johnson.

Despite the threats to his life, Dr. King refused to carry a gun for protection, asking, “How could I have claimed to be the leader of a nonviolence movement then?”

On April 3, 1968, King was headed to Memphis to help settle a strike by garbage workers. When a bomb threat — not the first — delayed his flight, the shaken leader seemed to sense his own mortality.

After telling the congregation at the Mason Temple Church about the bomb scare, King said, “I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight that we, as a people, will get to the promised land. And I’m happy tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.”

Nearly 24 hours later, his words turned to grim reality. It was as if King’s sixth sense and multiple sources of hate had converged in a single, fateful moment.

At 6:05 PM on April 4, as King stood on the second-floor balcony outside his room at the Lorraine Motel, a shot pierced the still evening. King was hit. He was rushed to the hospital but it was too late — the 39-year-old husband and father was pronounced dead an hour later.

Memphis lawmen undertook an intensive manhunt for the killer. Newsman Dan Rather, whose CBS network broke the news to a shocked world, later said, “He had died as many, including Dr. King, had expected he would.”

The world was in shock, but his loss hit African-Americans the hardest. Stevie Wonder, then a teenage singing sensation, remembers, “I asked, ‘Why don’t they like colored people? What’s the difference?’ I still can’t see the difference.”

As the news of King’s assassination spread, riots broke out. Presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy, whose own brother, John, had also been slain by an assassin’s bullet, was devastated when he heard the tragic news.

“Oh, God. When is this violence ever going to stop?” he said.

That night, Kennedy gave an impassioned speech in Indianapolis, honoring his late friend’s legacy.

“What we need in the United States is… love and wisdom, and compassion toward one another, and a feeling of justice toward those who still suffer within our country, whether they be white or whether they be Black.”

As the world mourned, funeral arrangements were made. On April 5, King’s widow arrived in Memphis on a flight arranged by Kennedy. Hundreds streamed into the funeral home to pay their last respects.

“Many of those who filed past could not control their tears,” Time magazine reported. “Some kissed King’s lips; others reverently touched his face… Mrs. King was a dry-eyed frieze of heartbreak.”

After the service, police and National Guardsmen escorted the procession to the airport, where King’s body was flown to Atlanta for his funeral.

Three months later, on June 5, 1968, the nation was rocked by the shooting of Robert F. Kennedy in Los Angeles. In the wake of these tragedies, Americans of all colors sought to understand what was happening to their great land — and what might happen next.

Charlton Heston, who knew Dr. King, said, “I don’t think Robert Kennedy’s death reveals a hidden core of violence in the American spirit.” He added that while dissent was essential to a healthy and free society, “disorder breeds violence, and violence breeds murder. We must somehow break this chain.”

African-American TV star Diahann Carroll, then starring in the trailblazing TV series Julia, lamented, “In the face of this kind of national tragedy, could anyone really care about Julia and her humorous little racial and personal difficulties?”

The answer was yes. What had to come next was a return to normalcy — and a return to the mission Dr. King had set for the nation.

Yet it was a goal that had actually been set in motion years earlier by another pair of Kings — Martin’s father and mother.

Martin Luther King Jr.’s journey came to an abrupt end the night of April 4, 1968, on a hotel balcony in Memphis. The chain of events that placed him in that exact time and place appeared to be inconsequential at the time. But though he didn’t know it, his final moment had begun months earlier, with the stench of garbage.

On Feb. 1, 1968, two Memphis trash collectors, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, were crushed to death by a malfunctioning garbage truck. Frustrated by the city’s lack of response to this deadly accident, 1,300 Black employees from the Department of Public Works went on strike. Black sanitation workers, unlike white workers, received no pay if they stayed home during bad weather, and they were paid significantly less with no overtime.

At a union meeting on Feb. 11, the African-American sanitation workers unanimously walked out with the full support of the local NAACP.

When police used tear gas to break up a nonviolent march by the strikers, a minister, James Lawson, enlisted King’s help. The civil rights champion traveled to Memphis on March 18 to encourage a crowd of 25,000 labor activists to support the strike.

“You are demonstrating that we can stick together,” he told them. “If one Black person is down, we are all down.”

King promised to return, and on March 28 he led a march through the city. On that day, 22,000 students skipped school to join in. King, who’d arrived late due to a snowstorm, found himself leading a surging, out-of-control protest that turned violent. He was hurried to safety at a nearby hotel.

The scene he left behind was chaos. Shops were looted; police shot and killed a 16-year-old marcher, and protestors who sought sanctuary in a church were tear-gassed and clubbed. The mayor brought in the National Guard to restore order. Discouraged and disappointed — but refusing to give up — King left for Atlanta. But on April 3 he returned to Memphis, where he addressed a crowd of sanitation workers who had braved a snowstorm to join him at the Mason Temple. There, the powerful orator delivered his inspirational “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech.

“Something is happening in Memphis; something is happening in our world,” he told them. Later in the speech he uttered the fateful words, “Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will.”

It was the last address King would ever make.

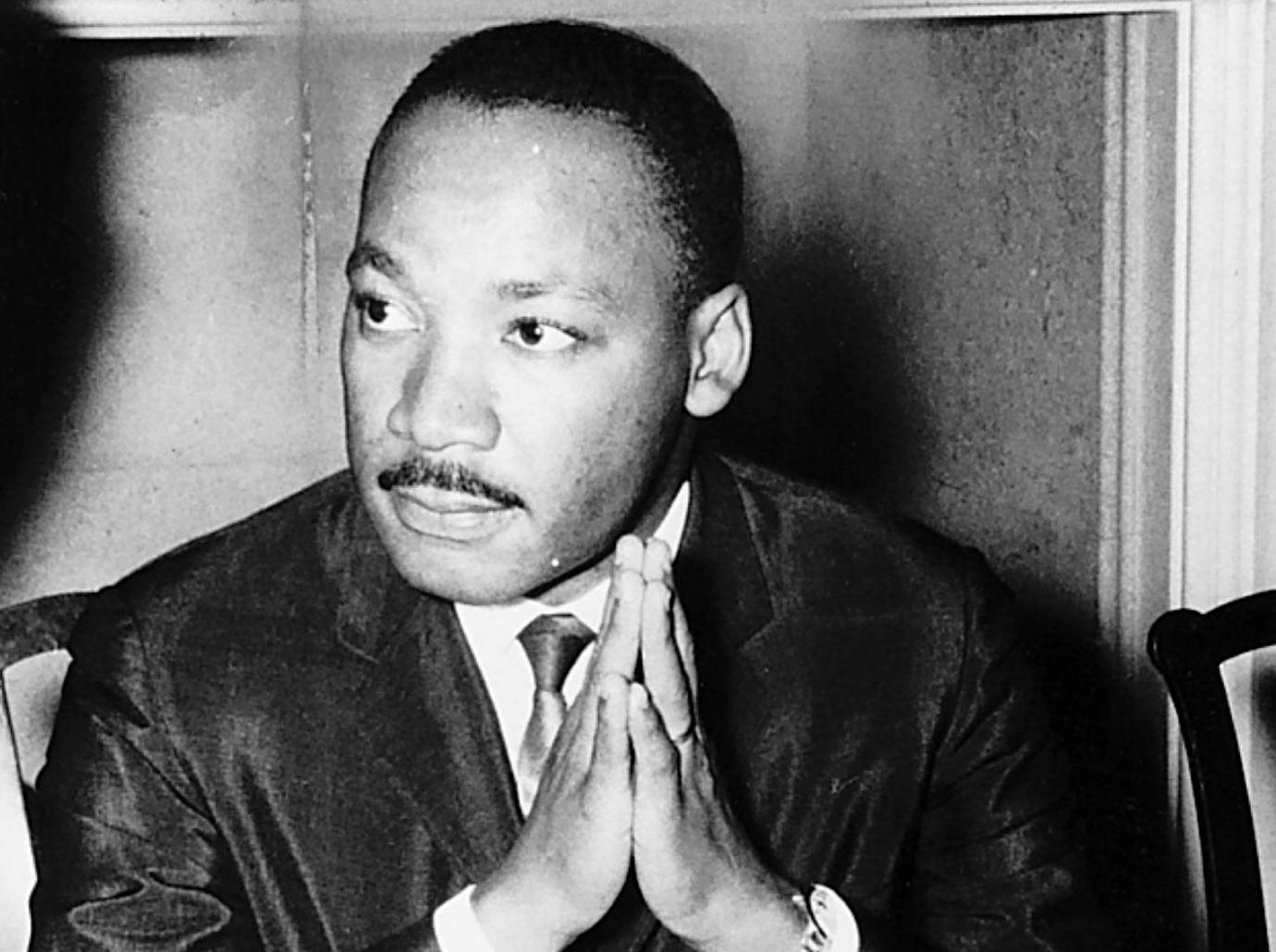

On Thursday, April 4, King was lodged at the Lorraine Motel in room 306 with close associates Rev. Ralph Abernathy, Jesse Jackson, Andrew Young, Hosea Williams, and several others, including a Life magazine photographer.

The weary civil rights leader stepped out onto the balcony outside his room and stood quietly, breathing in the fresh air. At 6:05 PM, the sharp report of a rifle shattered the silence. King fell violently backward onto the balcony, mortally wounded.

“There was this ringing shot that hit him in the neck and went down and apparently blew his heart out,” Jackson said later. “He never knew he was hit.”

Witnesses cried out and pointed to a flophouse across the street where the shot had come from, hoping someone would apprehend the gunman. When police arrived, other eyewitnesses reported that they had seen a man flee the rooming house after the shot was fired. A package recovered close to the site contained a Remington rifle and binoculars — both with fingerprints.

The FBI identified the suspect as a two-bit criminal named James Earl Ray, 40, who had been eluding capture.

Meanwhile, at St. Joseph’s Hospital, doctors attempted cardiopulmonary resuscitation on King, but the 39-year-old civil rights icon never regained consciousness. The time of death was recorded as 7:05 PM.

As news of King’s death spread on TV and radio, riots broke out in Washington, D.C., Baltimore, Chicago, and Kansas City. In New York City, after a disturbance began in Harlem, Mayor John Lindsay traveled to the predominantly Black neighborhood to express his sorrow. His calming presence helped avert riots throughout the city. Los Angeles community activists worked hand in hand with the LAPD to cool the mounting rage. Together they avoided a repeat of the devastating 1965 Watts riots.

Washington, D.C., was another story. A peaceful protest led by activist Stokely Carmichael erupted in violence. When the angry crowd of 20,000 overwhelmed a 100-member police force, President Lyndon Johnson dispatched 13,600 federal troops to the beleaguered city to restore order. The following day, rioters reached within two blocks of the White House. By the time the city was calmed on April 8, 1,200 buildings had been torched, including 900 stores. Damages were estimated at $27 million.

In Chicago, riots persisted throughout the weekend. Despite the widespread violence, the South Side was largely spared due to the effort of two street gangs, the Blackstone Rangers and the East Side Disciples, who cooperated with the city to help maintain order.

On April 7, the nation’s flags flew at half-staff for a national day of mourning. The following day, April 8, a stoic Coretta Scott King, accompanied by her four children and a crowd of 40,000, led a silent march through the streets of Memphis to both honor her husband and — lest they be forgotten — to support the city’s striking Black sanitation workers, as King had promised. Soon after, the city conceded to the strikers’ demands. Though King would not have been pleased with the violence, he would have been gratified by this victory.

Two days later, at 10:30 AM, funeral services were held in Atlanta at King’s beloved Ebenezer Baptist Church. Some 1,300 mourners listened to Rev. Ralph Abernathy’s sermon about “one of the darkest hours of mankind.”

At his widow’s request, King eulogized himself, as a recording of his last sermon at the church was played. In it, he requested that at his funeral no mention be made of his honors. Rather, he wanted to be remembered for his efforts to “feed the hungry… clothe the naked… love and serve humanity.”

Following the televised service, a funeral procession of 100,000 mourners walked to an open air memorial held at Morehouse College. The Southern Christian Leadership Conference provided security, while Atlanta police kept cars and dignitaries moving. Regrettably, a state funeral had been denied by Georgia’s Democratic Governor, Lester Maddox. Instead, the segregationist stationed 64 riot-helmeted troopers at the steps of the state capitol as the procession passed.

President Johnson, who was under pressure for his policies in Vietnam, feared his presence at King’s funeral might draw protestors, so he sent in his place Vice President Hubert Humphrey. Ironically, no modern president had done more to advance the cause of civil rights than LBJ.

Among the most honored and distraught of mourners were King’s parents, Martin Luther King Sr. and Alberta King. Also in attendance were Dr. King’s close aides Jesse Jackson and future Atlanta mayor Andrew Young. Friends and admirers also gathered to pay their final respects, including entertainers Harry Belafonte, Sidney Poitier, Ossie Davis, Marlon Brando, Sammy Davis Jr., Diana Ross, Bill Cosby, Paul Newman and Mahalia Jackson.

National and world leaders in attendance included Ted Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, Jackie Kennedy, Richard Nixon and Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie. Among the other luminaries present were author James Baldwin, jazz trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie and baseball legend Jackie Robinson.

After the memorial, a farm wagon drawn by mules carried King’s casket to South View Cemetery. In 1977, his grave was moved from South View to the plaza between the King Center and the Ebenezer Baptist Church.

King’s suspected killer, James Earl Ray, was captured on June 8, 1968, at London’s Heathrow Airport while attempting to travel to the United Kingdom with a fake Canadian passport. He was extradited to the United States and sent to Memphis to face murder charges.

On March 10, 1969, to avoid the state’s death penalty, Ray confessed to the murder of Martin Luther King Jr. He was sentenced to 99 years behind bars. Three days later, he unexpectedly recanted his confession and demanded a new trial, claiming that he was the victim of a vast conspiracy and had been framed by a mystery man known only as “Raoul.”

Ray (who died in 1998 at age 70 from complications related to kidney disease and liver failure) spent the rest of his life declaring his innocence and attempting to secure a new trial.

He had some very surprising supporters in his corner...

After Dr. King was ruthlessly slain by a single gunshot, the FBI was quick to pronounce career criminal and fugitive from prison James Earl Ray, 40, as their prime suspect. Eluding the feds, Ray was the target of an international manhunt that lasted for two months. Captured in London on June 8, Ray was extradited to the U.S. to face justice.

The evidence the FBI had in its possession was meager: a Remington rifle with Ray’s fingerprints on it. The gun was his, but was it the actual weapon used in the shooting? Ballistics said that the bullet removed from the slain leader was too mutilated to be analyzed. But experts, including Judge Joe Brown, who presided over Ray’s failed appeals, disagreed.

“The FBI never conducted any meaningful tests on the weapon,” Judge Brown said. In 1997, he ordered new tests on the rifle that had been found near the crime scene. The most advanced scientific tests of the time failed to prove it was the murder weapon. Witnesses had told police they had seen a man fleeing the crime scene, but no one could state definitively that it was Ray.

Unfortunately for justice, the facts in the case remained mere hearsay because James Earl Ray had no trial. On the advice of then-lawyer Percy Forman, Ray entered a guilty plea on March 10, 1969. Instead of the death penalty — which in Tennessee was carried out by way of the electric chair — he received a 99-year sentence. Three days later, Ray recanted his confession, but it was too late.

And without a trial, no evidence was ever presented, no witnesses testified under oath, and no jury of Ray’s peers had the opportunity to reach a verdict — the very foundation of our justice system. As in the case of JFK’s assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald, there had been no due process. Dead men tell no tales… and men in prison have no one to tell.

Effectively confined for life, Ray had plenty of time to reflect on the events that had delivered him to his fate.

The eldest of nine children, Ray was born to George and Lucille Ray in Alton, Ill., on March 10, 1928. His father was far from a model citizen. After a brush with the law for passing bad checks, George took his family on the run. Settling briefly in Ewing, Mo., the family suffered a terrible loss when their daughter Marjorie, playing with matches, suffered a fiery death.

Striking out on his own, Ray was a drifter who couldn’t hold a steady job. In 1945, he joined the Army and was stationed in West Germany. A habitual drunk who escaped from a federal stockade, Ray was dishonorably discharged three years later.

“The brother I knew as a boy who went into the Army never came home,” sibling John Ray recalled.

Returning to the U.S., Ray immediately ran afoul of the law. His first burglary conviction came in 1949. Subsequently arrested for armed robbery, Ray spent another two years in jail. After he was convicted of mail fraud in 1955, Ray was sentenced to four years at Leavenworth. Paroled, Ray was busted again for armed robbery. This time, there would be no judicial revolving door. Ray received a 20-year sentence.

In April 1967, Ray broke out of Missouri State Penitentiary by hiding in a bread truck and made his way to Mexico. There, under the alias “Eric Starvo Galt,” he made cheap mail order porno films.

A lifelong racist, Ray returned to the U.S., settled in Hollywood, and was drawn to the presidential run of segregationist Alabama Governor George Wallace. After a quick nose job to alter his appearance, the fugitive drove cross-country to Atlanta and checked into a rooming house. It’s here that the FBI later said they found a map with Martin Luther King Jr.’s church and home circled.

Ray then traveled to Alabama loaded up on guns and ammo for a purported hunting trip with his brother John. Instead, on April 2, 1968, Ray packed his bags and drove to Memphis. What followed has been etched in history as irrefutable fact. John Ray calls it something else: a lie.

“Just before King’s assassination,” John recalled, “I met Jimmy in a bar. He was scared. He felt like he might be getting set up in some kind of operation. He didn’t know it involved Dr. King. As the evening wore on, he convinced himself he was being paranoid. That was the biggest mistake of his life.”

According to the official FBI story, Ray stalked Dr. King for months, and finally tracked him to Memphis, where he killed the civil rights leader.

From prison, Ray persisted in his claim that he was not the shooter but a patsy. As he repeated the story, more and more people began to listen. Trapped behind bars, Ray began to fear that he might be silenced permanently.

In 1971, leaving a dummy in his cell bunk, he sawed through the bars with a smuggled hacksaw, squeezed through the fan blades of the ventilation system and crawled up an air shaft. When he reached the prison yard, the only way to freedom was though a steam tunnel. It was 400 degrees inside. Ray was forced to surrender.

On June 10, 1977, Ray busted out of prison again, along with five other convicts. He disappeared into the dark backwoods of Tennessee and, recaptured three days later, had another year added to his sentence, making it an even 100.

Ironically, it was the government that finally gave Ray the chance to be heard. In August 1978, he met with investigators from the House Select Committee on Assassinations. In a series of detailed interviews, Ray told them he did not kill Dr. King. He contended that a mystery man named “Raoul” had manipulated him through every detail of an elaborate gun-running scheme. The Remington rifle that Ray had bought earlier was a “sample” to show prospective buyers. The arms deal was set to go down in the Memphis rooming house across the street from the Lorraine Motel. Raoul was to keep watch in the room while Ray chilled until the buyers showed. Ray went to the movies and learned of the assassination over the car radio. He told investigators he never saw Raoul again.

After further analysis, the House Committee agreed that there was circumstantial evidence of a conspiracy to kill Dr. King.

Walter Fauntroy, who served on the committee, noted, “I find it difficult to believe that James Earl Ray, acting alone, pulled off the crime of the century, was able to get out of Memphis… and go all the way to Europe without help.”

The testimony did not sit well with someone. In 1981, Ray’s greatest fear was realized when he was stabbed 22 times by three fellow inmates. The convict received 77 stitches during an hour-long surgery. Pulling through, he soon found some rather unlikely allies in his corner.

The first was Jesse Jackson.

After meeting with Ray, Jackson believed he was innocent — so much so that he wrote the foreword to Ray’s 1993 book, Who Killed Martin Luther King? The True Story by the Alleged Assassin.

“I have never accepted the ‘one crazy man’ of political assassinations,” Jackson wrote. “I have always believed there was a conspiracy involved in Dr. King’s assassination.” He added that if his beloved friend and mentor had survived the shooting, he would have been the first one to demand a fair trial for the alleged assassin.

Ray’s other ally was Martin’s son Dexter Scott King. In 1997, King met with Ray and asked him directly: “Did you kill my father?”

“No, I didn’t,” Ray replied. “I ain’t had nothing to do with shooting your father.’’

“I believe you,” Dexter said, adding, “My family believes you, and we are going to do everything in our power to make sure that justice will prevail.”

Despite numerous attempts by Ray’s lawyer, William Pepper, and a televised mock trial in which Ray was found not guilty, no real trial was ever granted. On April 23, 1998, Ray died from liver disease in a maximum-security hospital at age 70.

Yet, the King family was able to exact some measure of redemption for Ray.

In 1993, Memphis restaurateur Loyd Jowers appeared on ABC’s Prime Time Live. According to Jowers, the martyred leader’s death had been orchestrated by government officials and the Mafia in a hush-hush conspiracy. On the air, Jowers not only named the killer as deceased police Lt. Earl Clark, he even admitted hiring him!

Representing the King family, attorney Pepper successfully sued Jowers and “other unknown coconspirators” in a wrongful death civil suit. After four weeks of testimony from 70 witnesses and thousands of pages of evidence, a Memphis jury found that King had been the victim of a “conspiracy to do harm.”

The King family had only requested, and received, a $100 settlement, to prove that their interest was justice, not profit.

Following the 1999 verdict, Coretta Scott King said, “The jury was clearly convinced by the extensive evidence that was presented during the trial, that in addition to Mr. Jowers, the conspiracy of Mafia, local, state and federal government agencies were deeply involved in the assassination of my husband.

“The jury also affirmed overwhelming evidence… that James Earl Ray was set up to take the blame.”

As to how high the conspiracy went, some fingers pointed at FBI kingpin J. Edgar Hoover, who resented the power and influence of the African-American icon. Others pointed even higher.

Former Nixon White House aide Roger Stone said, “It would be very difficult for something of that magnitude to occur on LBJ’s watch and he not be privy to it.”

In 2000, the Department of Justice completed its own investigation, releasing a 150-page report that said there had been no conspiracy, that the assassin was Ray, and that he had acted alone.

James Bevel, King’s longtime colleague and assassination eyewitness, responded bluntly to that report: “There is no way a 10-cent white boy could develop a plan to kill a million-dollar Black man.”

Two years later, in 2002, a Florida pastor, Rev. Ronald Denton Wilson, said that his late father, Henry Clay Wilson, was the assassin. The elder Wilson, who was a Ku Klux Klan member, purportedly confessed on his deathbed. But his son provided no evidence to back his startling claim. “[My father] left no trail,” Ronald said.

Meanwhile, the top-secret FBI files on the assassination remain sealed until 2027 — a date eagerly awaited by Jesse Jackson.

“I will never believe that James Earl Ray had the motive, the money and the mobility to have done it himself,” Jackson said. “Our government was very involved.”