High Lives of NYPD’s Cocaine Cops – How New York’s Dirtiest Officers Ruled The Mean Streets

March 18 2022, Published 5:07 a.m. ET

In the 80s and 90s, crooked crews were running wild in the Big Apple, slinging cocaine, committing armed robberies, collecting “protection” cash and shaking down drug dealers. And that was just the police!

And nowhere was the corruption more ingrained than in “The Seven Five,” New York’s 75th Precinct.

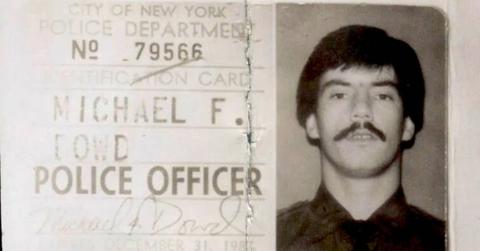

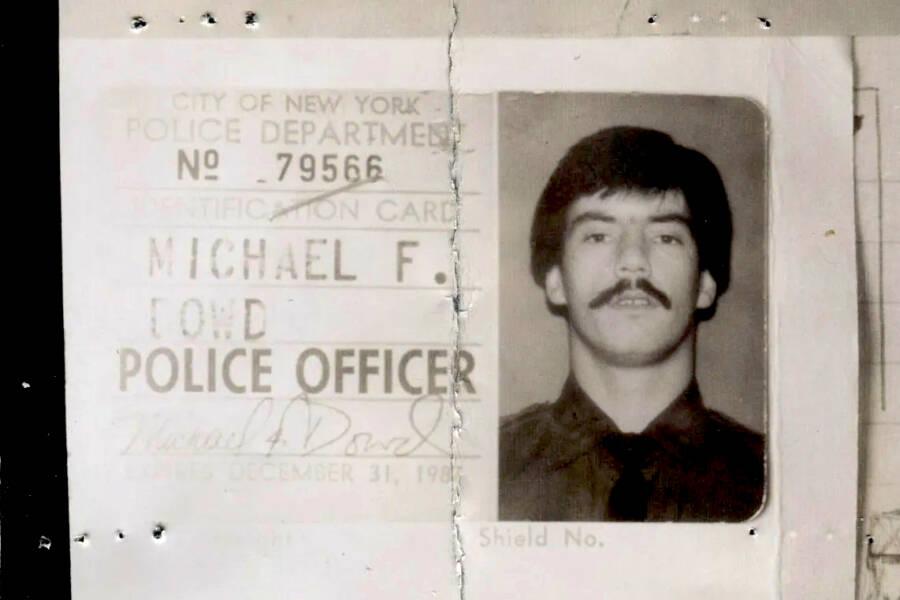

Bent cops like Michael Dowd and Kenneth Eurell — patrol partners condemned in the New York newspapers as the most crooked officers on the city’s thin blue line — thought they were above the law, wielding their badges as the ultimate cover for their own illicit activities.

“It was like going outside your body, doing the things we did,” Eurell would later say. “I knew it was crazy. I knew it was going to have to have to come to an end.”

It was his partner in crime, Dowd, who made the front page of the New York Daily News on September 28, 1993, as “the dirtiest cop in N.Y.”

Eurell wore a wire and ratted on Dowd after the out-of-control cop plotted to rob and murder a drug dealer’s wife and run away to Nicaragua with the money. Eurell was rewarded with a mere three-month sentence, while his partner went down for 12 years. It was a long time for Dowd to think about just where he’d crossed the line from ambitious young cop battling for justice to outlaw in a blue uniform who’d sold his soul for dirty money.

In an interview given after he was released from prison, Dowd remembered as the turning point taking a bribe from a teenager to look the other way at a traffic stop. With $200 in tainted cash burning a hole in his pocket, the 23-year-old — whose paltry NYPD wage left him feeling “unappreciated,” he said — never looked back.

It was the ’80s, and cocaine was flooding into New York City, bringing with it an unprecedented crime wave. In 1988, there were 100 murders in Dowd’s five-square-mile Brooklyn precinct alone, second in homicides only to the infamous 48th Precinct in the Bronx.

Drugs were so prevalent that Dowd claims cops were dissuaded from making arrests because it was too expensive for the city to process them all.

From stealing cash — and stash — from the dealers, Dowd progressed to working for the drug lords, protecting them and tipping them off to any police raids. Eventually he moved into trafficking and dealing drugs himself.

He later explained how easy it became to pocket the dirty cash he seized on drug raids. He recalled, not long after taking the motorist’s bribe, being the first to arrive at the scene after a shooting at a drug house.

“I show up and I can’t get in the building because the guy’s head is blocking the door,” he said. “I’m literally walking over his body to get in. Inside you can see his partner — they were young kids — wiping the blood of his best friend off his hands.

“So as it turns out, there’s money and drugs there — a lot. I see a separate stash of about $800. This guy’s not paying attention. So I take it.

“It was weird. I just put it in my pocket. Then the investigators show up. There’s about five pounds of reefer, $500 of cash. The sergeant goes, ‘Is that it?’ And he looks at me and I felt like he knew. So I took the $800 out of my pocket and I gave it back.

“I was still at that point of feeling uncomfortable about taking anything.”

Later that night, Dowd saw the sergeant at a local bar and approached him. “I said to him, ‘Sarge, when I handed you that money today, I took it out of my pocket. What do you think?’ He said, ‘I don’t give a f*** what you do before I get there... and if I happen to get there and you’ve already got something, I didn’t see it.’

“Bingo! A light went on. Like, people do this, you ain’t the only one. It was like I had permission now.”

From then on, Dowd said, “I made sure I was first on a crime scene.”

He took bags of money from drug houses, as well as guns and cocaine. At the time, a kilo of cocaine went for $34,000. When he found a stash, he said, his first thought was, “Pay dirt!”

“I did something wrong,” he explained. “We all knew it was wrong, myself especially, but it was an addictive excitement.”

As a result, Dowd lived like a king for almost a decade, buying a string of properties and brazenly driving a brand-new red Corvette to work, immune to the gossip circulating among his $600-a-week colleagues on the force.

Dowd’s corrupt methods were the precinct’s most poorly kept secret — but in those days, the aversion to snitches was so strong, nobody spoke up. Not even a corruption crackdown in 1986, which resulted in 13 officers from the 77th Precinct being arrested, deterred him.

The next year he got a new partner, Kenneth Eurell, and, if anything, the criminal activity stepped up. Dowd struck a deal with a local drug baron, Adam Diaz, to protect his activities in return for a $24,000 down payment and a weekly $8,000 retainer.

“My wife [Bonnie] kept telling me to stop,” Dowd recalled. “But I couldn’t stop. I loved the extra money so much, and I spent it very openly. I thought about getting caught, and then I’d dismiss it because I was getting away with it for so long right in front of everybody, and I thought none of the cops would give me up.”

In the end, it took Eurell, Dowd’s partner — both on patrol and on the take — to bring him down. By 1990, the team had their own drug dealers working the streets of Long Island — one of whom became the target of a local police drug-squad sting.

As the drug cops kept surveillance on the dealer, it slowly dawned on them that he was being run by their fellow officers.

Even after being arrested, Dowd still thought he could ride it out and keep his job. What he didn’t know was that the FBI was also on his case — and had enlisted the help of his partner, Eurell, in return for a lenient sentence.

The wire evidence from Eurell was enough to convict Dowd in 1994 of racketeering and conspiracy to distribute narcotics.

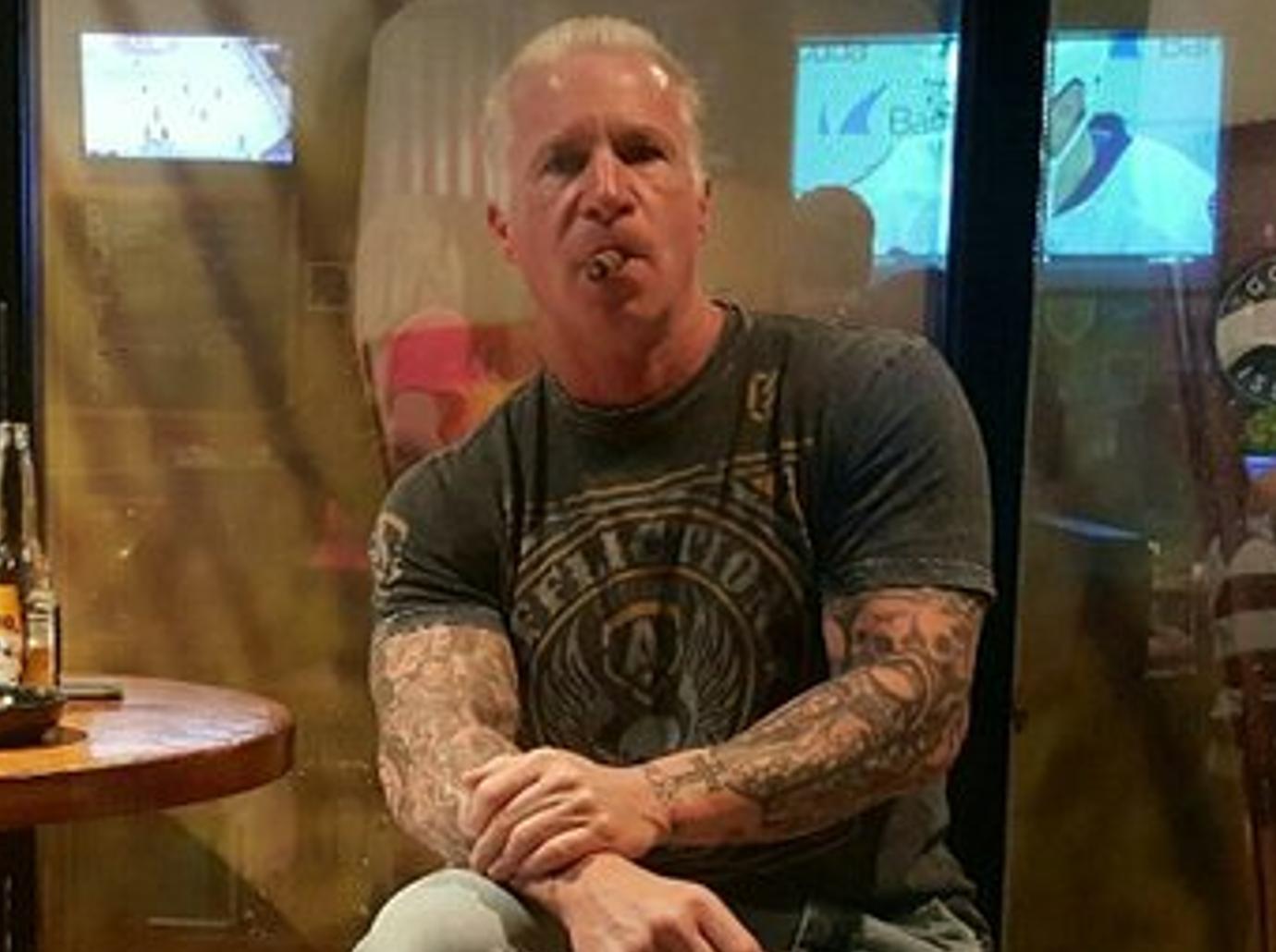

Eurell now says that he regrets ever having met Dowd. “I wasn’t evil; I was young and dumb,” he told an interviewer in Tampa Bay, Florida, where he now resides.

Dowd, who’s still living on Long Island, also wishes his life had turned out very differently.

“I never went in planning to be a bad cop,” he said.“I wanted to be a good cop. I have a dream all the time [where] I’m wearing a uniform and I’m being a good cop. “That good cop’s still in me. He just chose the wrong path.”

Ken Eurell