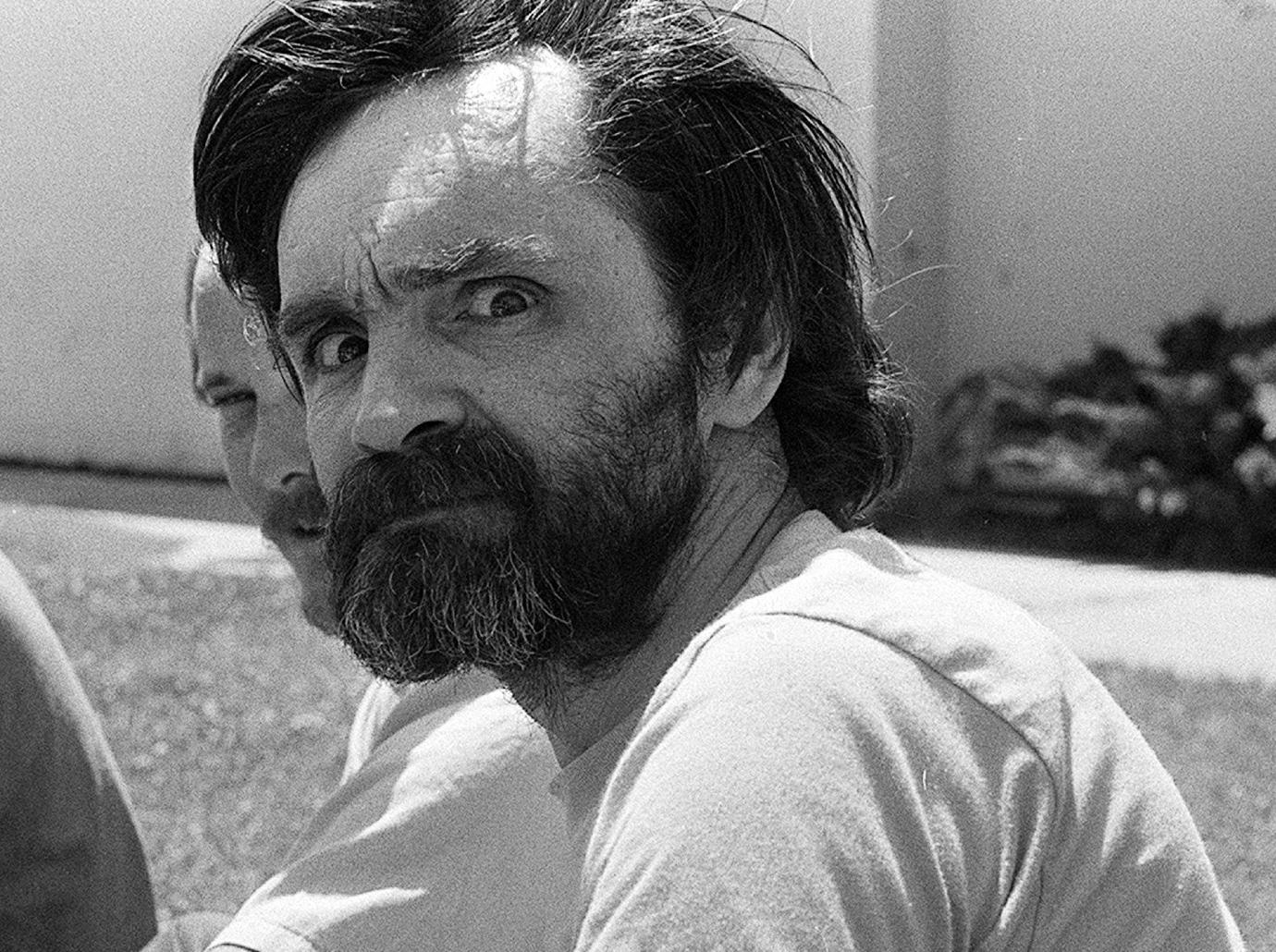

A Week After The Tate-La Bianca Murders, Charles Manson & 26 Members Of His Gang Were Arrested Then Released – Here’s Why

July 11 2021, Published 12:08 p.m. ET

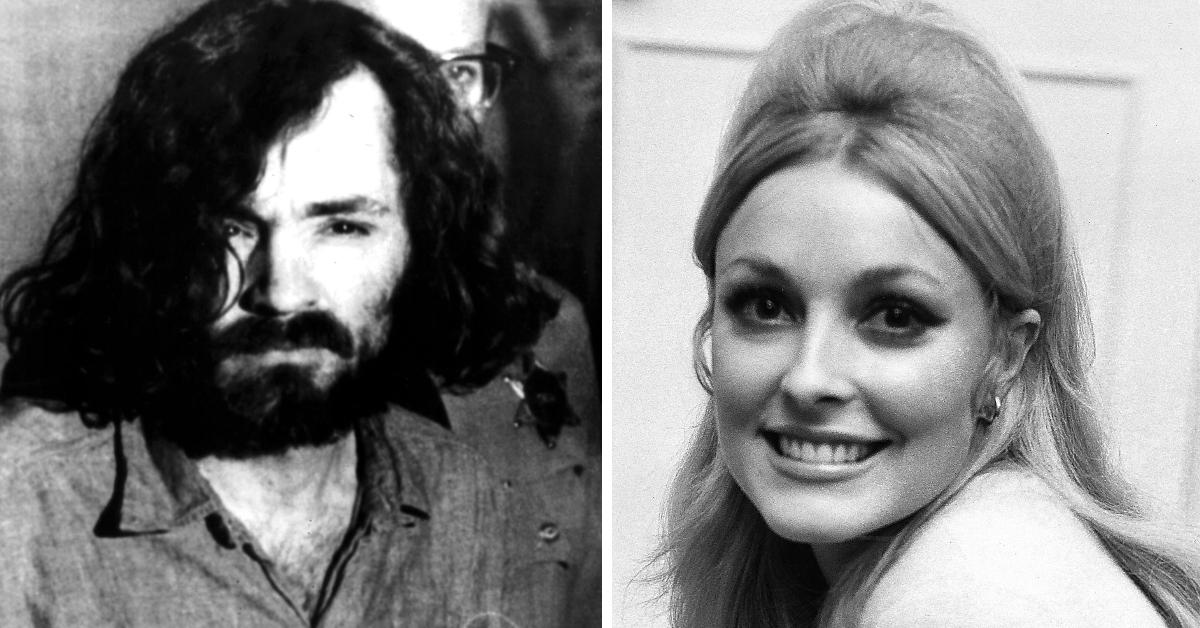

On August 8, 1969, Charles Manson and his “Family” cult butchered their way into history. Four members of the gang broke into Sharon Tate’s house in Beverly Hills and slaughtered the 8-months-pregnant actress, along with four of her friends. The following night they repeated the horror when they murdered Rosemary and Leno LaBianca in L.A.’s Los Feliz area.

In both cases, the gang did not content themselves with merely killing their victims – they tortured them and then desecrated their bodies, writing slogans on the wall in their blood in an attempt to incriminate the Black Panthers.

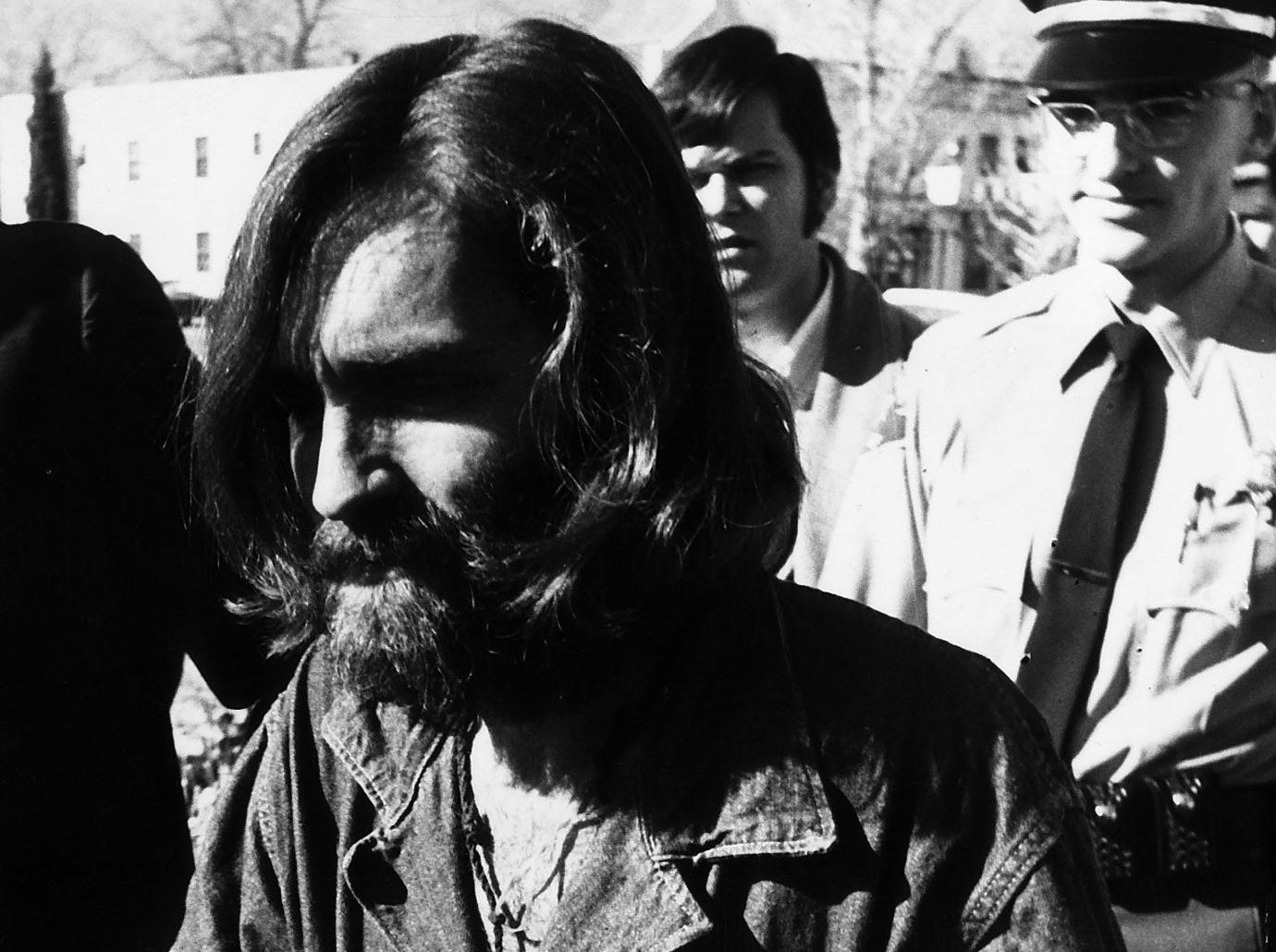

The killings made headlines the world over and horrified an America still in thrall to the “peace and love” vibe of the hippie era, but shockingly remained unsolved until October that year when Manson was finally taken into police custody, only later being charged with the murders in December, some four months after committing them.

But according to the book The Last Charles Manson Tapes: Evil Lives Beyond the Grave, by investigative journalists Dylan Howard and Andy Tillett, just one week after the murders, the police had Manson and the core of his cult in their hands -- and let them go again. “Two days later, all charges against him and his Family were dropped,” they write, and the crazed killer would even go on to claim one more victim.

The Tate-LaBianca murders, as they came to be known, were not random slayings but part of a carefully thought-out plan that Manson dubbed “Helter Skelter.” They were intended to be the catalyst for an apocalyptic race war that the Family would see out from a fortress in the desert, emerging afterward as leaders of a white master race.

As Howard and Tillett explain, the plan was for the cult to abandon their base at Spahn Ranch on the outskirts of L.A. for a hideaway in Death Valley called Barker Ranch.

“Manson knew he needed to go to Barker Ranch, deeper into the desert, to avoid the worst of the anticipated uprisings,” they write. “And that meant he had to spur Family members to work harder than they ever had.”

They also quote Family member Catherine Share. “We never had newspapers at the Spahn Ranch, but Charlie got an LA Times with headlines about the Tate/LaBianca killings," she said. “He held it up and said, ‘It’s started.’ He said we had to get out of town because it was now dangerous. We were up day and night putting food into barrels and getting our last clothes together, the leather outfits we’d been working on. We had three dune buggies with roll bars and machine gun mounts. It was apocalyptic."

“[W]e’d learn to live off the land. We’d live in the desert and come in on dune buggies and rescue the orphaned white babies. We’d be the saviors. I believed that the cities were going to burn. I believed my only safety was to stay with the Family. I believed Charlie knew best.”

The cars were a crucial part of Manson’s Helter Skelter plan. Not only would they have to transport his entire cult – at that time several dozen strong – deep into the desert, but once there, the reconfigured vehicles would act as a fast, mobile defense against any attack.

And then, seven days after the slaughter at Sharon Tate’s mansion, all of Manson’s grand plans seemed to come undone.

“At dawn on Saturday, August 16, more than one hundred law-enforcement officials swarmed over the ranch, rousting sleepers, scaring animals, and seizing weapons and vehicles,” write Howard and Tillett. The police had come for Manson – and they had come in force.

“As helicopters buzzed overhead, ranch hands and Family members alike were rounded up like herds of cattle. In all, twenty-six people were arrested," the book states.

"Manson was dragged out from under one of the buildings and cuffed; he must have been terrified the raid was in response to the Tate and LaBianca killings.”

Incredibly, however, the police were not looking for America’s most notorious killers but investigating reports that members of Manson’s cult had been stealing cars, and the ranch was being used to hoard unlicensed firearms.

“When the arrest warrant indicated authorities were looking for automobiles, auto parts, and guns, it must have been a relief,” they continue.

If that seems staggeringly incompetent now, worse was to come.

“Manson would have been even more relieved when, two days later, all charges again him and his Family were dropped,” explain Howard and Tillett. “The search warrant had the wrong date on it — the raid was originally scheduled three days earlier than it had occurred — and every one of the arrests was invalid.”

As well as failing to pin a single charge on the man who, at that point, had ordered and overseen the killing of at least seven people, the police raid also had another fatal consequence.

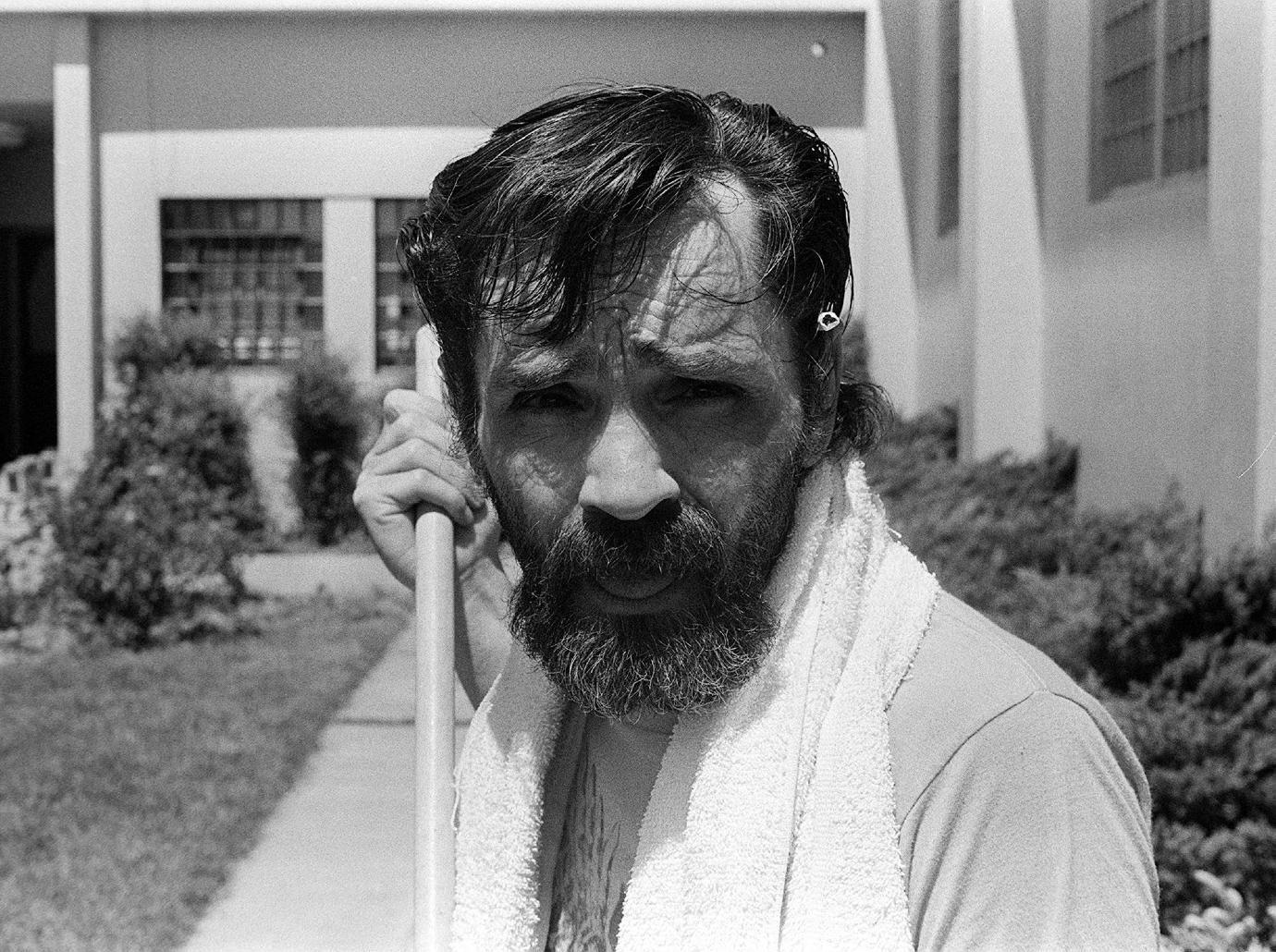

Charles Manson was convinced there was an informant in the gang and pinned the blame on Donald “Shorty” Shea, a ranch hand with whom he had previously fought.

Less than two weeks later, on August 26, he ordered Shea’s death. Manson would not be arrested again until October.