Chasing a fugitive for 45 years: How a cop solved the cold-case of what happened to the suspect who left him for dead

Dec. 14 2021, Published 10:35 a.m. ET

EDITOR'S NOTE: This is Part 2 of an exclusive look at a Colorado cop decade-long hunt to find the suspect who shot him. To read Part 1 click here.

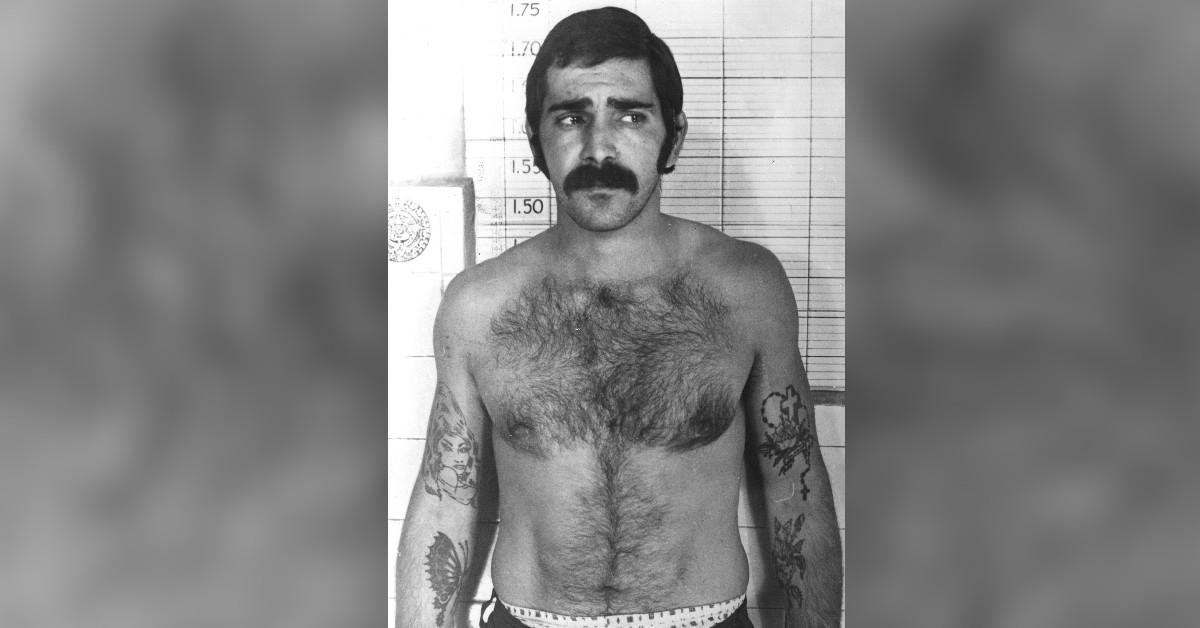

Lawrence Pusateri, fresh off the second prison break of his life, vanished into the foothills of New Mexico’s Sangre de Cristo Mountains in 1974. He was 31 years old, cunning and handsome, and looking for a fresh start with his newly created alias: “Ramon Montoya.”

Behind him, some 350 miles north, lived the angry cop he shot in Denver back in 1971. Then he was using the name Luis Archuleta. The city paid officer Daril Cinquanta $15,000 for his injuries, which he used to buy a house in the suburbs – command central for his pursuit of Pusateri.

By spring 1975, Cinquanta was out of leads and began to suffer debilitating fatigue. The hunt for the man who left him dead had gone gold.

Doctors diagnosed him with Lupus, an autoimmune disease. Cinquanta worried that his superiors would find out about the illness and take him off the streets, which would torpedo his career and blunt his chances of ever finding Pusateri. So he hid his illness from the police department.

That September, Cinquanta’s best informant dropped the biggest case of his career in his lap. Joseph “Joey” Cordova Jr. told him that key figures in the Crusade for Justice planned to bomb Denver police headquarters, four substations and a convention center that would host an annual gathering of the International Association of Chiefs of Police. The attacks were set to coincide with Mexican Independence Day on Sept. 16.

Cordova was a career criminal who had recently shot a crime associate in the face (not fatally) for refusing to hide stolen merchandise. But Cordova could not abide by the Crusade’s plans to murder innocent cops and civilians. When Cinquanta asked him to wriggle deeper into the orbit of the Crusade’s leaders, Cordova came up big. He told Cinquanta that a Crusade founder, Juan Haro, planned to bomb a police substation.

On the night of Sept. 17, 1975, investigators watched Haro walk out of his home, drop a plastic garbage bag in the back seat of a stolen car and climb behind the wheel. As he began to motor away, police zoomed up in cars to block him in.

One officer ran to Haro’s door, clubbing him in the head with a shotgun and dragging him out of the vehicle through an open window, recalled Cinquanta, who ran to the other side of the car and leaned in to open the trash bag. What he saw nearly stopped his heart — 27 sticks of dynamite rigged to a blasting cap with a stopwatch timer, and the bomb was ticking.

Members of the bomb squad seized the explosive and Cinquanta pulled Haro to a safe spot for a conversation he later recalled in his autobiography, “The Blue Chameleon.” Cinquanta warned Haro that if the bomb detonated and killed anyone, he faced murder charges.

“I built it,” Haro told him. “Let me disarm it. You just have to cut a wire.”

The bomb squad did it for him.

Cinquanta later credited Cordova for the bust, saying his informant was a dangerous criminal who also happened to possess the moral fortitude to prevent a bombing that would have killed an estimated 50 people. Cordova then quietly slipped into the Witness Protection Program.

A federal judge later sentenced Haro to six years in prison for possessing hand grenades.

UNFINISHED BUSINESS

By the late 1970s, Cinquanta worked so many long days in Denver’s four police districts that he had turned his home into “District 5.” He stocked his office with blank search warrants and affidavits for his late-late work. That way, if he got a midnight tip on a major case, he had time to type out a search warrant, wake up a judge to get it signed, assemble a team and kick down the suspect’s door before the ink dried.

Cinquanta was promoted to detective in 1977, and his “Harry Callahan” swagger ultimately made him a local media favorite. But some of his colleagues weren’t fans. One supervisor blew a gasket after learning Cinquanta carried business cards that read, “Detective Daril Cinquanta, Crimefighter.”

Six years later he joined the Career Criminal Unit, an all-star team that targeted more than 700 lawbreakers with multiple felony convictions. The unit estimated 10 percent of those criminals – some feeding staggering drug habits – created 80 percent of Denver’s crime. A local TV reporter talked Cinquanta and other detectives into letting him ride along, cameras rolling, for a series called “Super Cops.”

Much like the fictional Callahan, Cinquanta was targeted by internal affairs probes and ran afoul of a special prosecutor, who charged him with a slew of felonies for allegedly entrapping burglars and robbers he had tailed.

Luis Archuleta

Cinquanta recently said the charges disgusted him not just because he wasn’t guilty, but because entrapping crooks would have taken the sport out of making the collars. He eventually pleaded guilty to official misconduct, a misdemeanor, to make the whole thing go away.

He took a medical retirement in 1989, having drawn his service weapon countless times. But he never shot a soul.

But the man who attacked him remain free. The cold case of where he vanished, unsolved.

Cinquanta soon resumed his unfinished business, hanging out his shingle as a private eye and making the hunt for Pusateri his number one priority. He placed regular calls to his informants, rattled the cages of Pusateri’s former associates in the Crusade for Justice, and sometimes prayed to God for help.

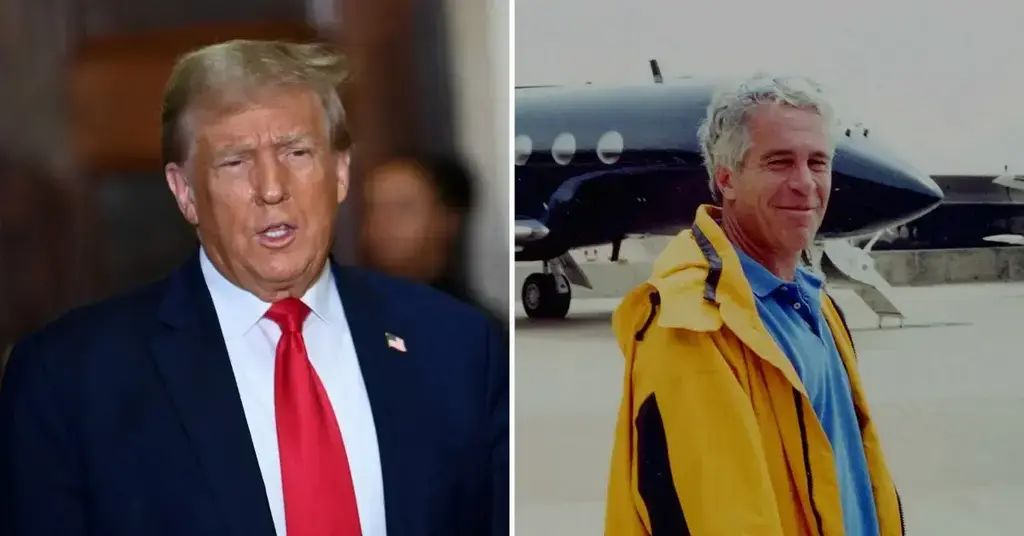

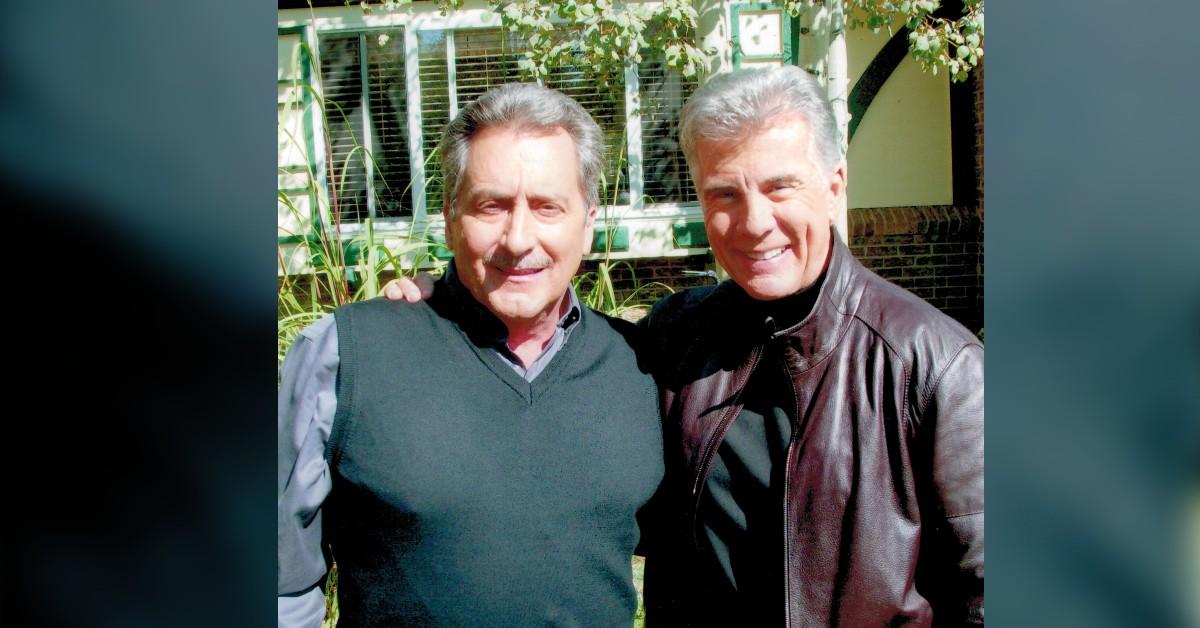

Then he appealed to perhaps a higher power: He wrote letters to “America’s Most Wanted,” hoping the gods of the popular TV show would air a segment on Pusateri – and it worked. Host John Walsh interviewed Cinquanta in Denver and “America’s Most Wanted” aired a segment on the Pusateri case in November 2009. The 11-minute piece opened with a recreation of the Juan Haro attempted bombing case.

“It’s just one of the stories that has made Daril a legend right here in Denver,” Walsh told viewers, noting that Cinquanta was writing a book about his career. “But there’s one chapter in Daril’s book that he’d really like your help on. You see, right now he’s not real happy with what he’s got to work with for an ending. The bad guy in this chapter is the only man who ever got the drop on Daril.”

The segment later cut to a recreation of Cinquanta’s 1971 shooting, then back to Walsh as he shook the former cop’s hand. “You know,” Walsh said, “I wouldn’t be surprised, once we put this white-hot spotlight on this creep, Pusateri’s gonna go down.”

Didn’t happen.

Then, nine years later, the U.S. government quietly canceled its warrant for Pusateri’s unlawful flight to avoid prosecution. The cold case seemingly over.

THE CALL

Cinquanta wasn’t done with the case. He continued to plug away on the hunt for Pusateri from the windowless confines of Professional Investigators Inc., which still occupies the basement of his ranch-style home in the burbs.

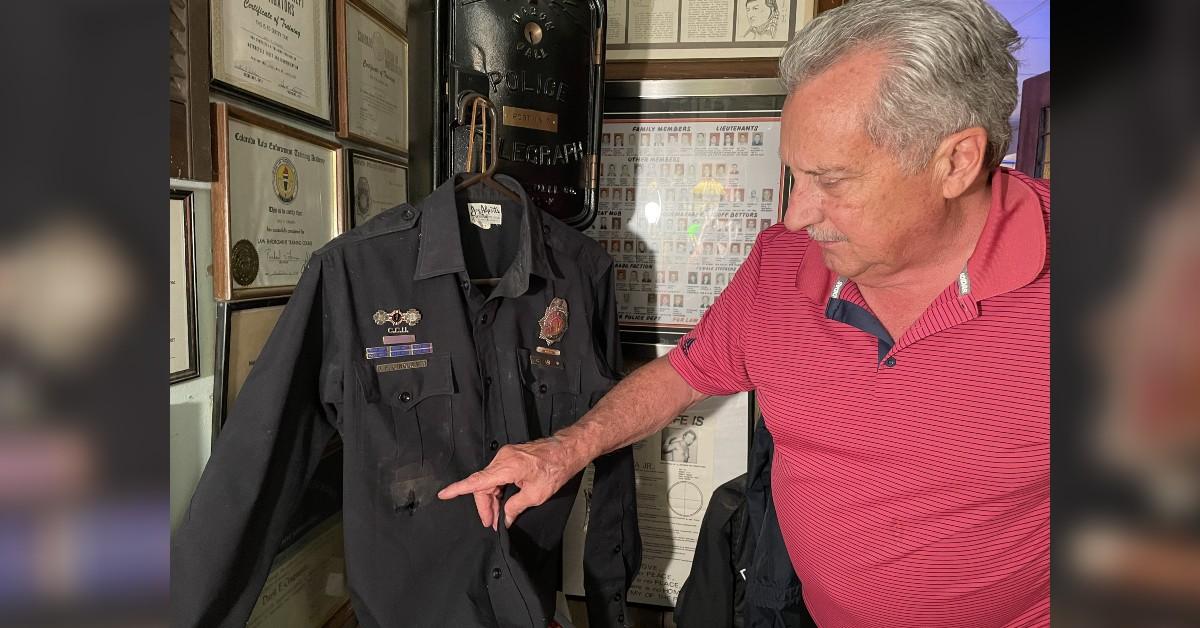

It’s a combination private-eye business, man cave and police museum, complete with stacks of file folders and I-love-me walls plastered with police medals and commendations and framed news clips from his biggest cases. A flip book of black-and-white mugshots rests atop a glass case. A full-length skeleton hangs in one corner and the police shirt he was shot in – still sporting bullet holes and an evidence tag – hangs in another.

On the morning of June 24, 2020, Cinquanta’s 72nd birthday, he was upstairs eating in the kitchenwhen his personal cell phone rang.

“Is this Daril Cinquanta?”

He didn’t recognize the voice.

“I’ve decided,” he said, “to tell you where the guy is who shot you.”

Cinquanta was skeptical but scribbled notes.

The tipster, whom he recalled calling from an anonymous line, told him his assailant lived in Española, New Mexico, with his common-law wife Esther Chacon. He provided the address, then hung up. The assailants name Roman Montoya.

Cinquanta hurried downstairs and searched his databases, quickly finding a “Ramon C. Montoya,” whose listed date of birth was in January 1944. Curiously, Montoya obtained a Social Security number in 1975, not long after Pusateri’s escape from the state hospital in Colorado.

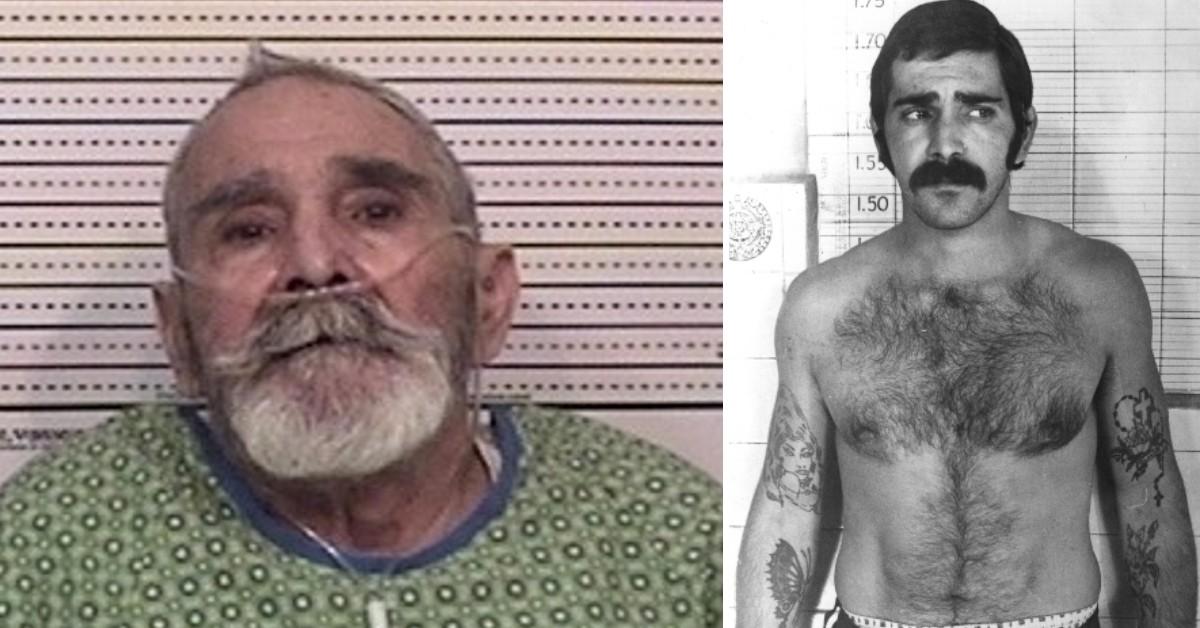

Montoya, he discovered, had been arrested in 2011 for suspected impaired driving in Hernandez, New Mexico. (Those charges were later dropped.) Cinquanta now turned to mugshots.com to see if he could find a booking photo from that arrest. And there he was, an aging version of the man who shot him in 1971.

The man known as Luis Archuleta in 1971 and the man who seemingly vanished for decades.

Luis Archuleta in a booking photo and in the 1970s.

Cinquanta phoned the Española Police Department and told Lt. Abraham Baca the story. Baca hung up and contacted FBI Special Agent Kyle Marcum, in Albuquerque, and together they sought to confirm Cinquanta’s story. But there was trouble. The fingerprints from Montoya’s 2011 drunk driving arrest had never been submitted to the FBI’s automated fingerprint system.

Agent Marcum and Española detective Byron Abeyta paid a visit on Montoya’s ex-wife in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

The investigators showed Darlene Montoya photos of Lawrence Pusateri and asked if she recognized him. At first, she told them she did not. But later in the interview, she admitted she misled them out of fear, according to an FBI affidavit. The man in the photos, she told them, was indeed her ex-husband, Ramon Montoya, the father of their three adult children.

At Marcum’s behest, she phoned her son Mario Montoya.

Mario, now 44, recalled the conversation. His mom’s voice had quavered as she made small talk and then told him that a man there wanted to speak with him. Mario then found himself speaking to an FBI agent.

“I knew instantly what it was,” he said.

Five or six years earlier, Mario explained, his dad had revealed his true name to him so that he might go online to help him find his mother. Mario picked up his phone and Googled the name of the grandmother he had neither met nor heard of, discovering she died years earlier.

His father also shared a darker secret — He was a long-sought fugitive who had once shot a police officer and might hold some sort of record for his time on the run. Mario recalled how terrified his father appeared as he described the immediate aftermath of shooting Cinquanta, he feared that he had killed him, and he was profoundly grateful to learn later that the officer survived.

As his dad spoke, Mario remembered, tears welled in his eyes.

Those revelations about his father and the Montoya name – an alias, a fabrication – had not left Mario angry, but bewildered. The news, he recalled, forced him to ask himself hard questions: “Who am I? What am I?”

Mario met with investigators on the very afternoon he first spoke to the FBI agent, identifying the man in their photos as his dad. They told him that they were going to arrest his father and sought his help. Mario told them his father posed no physical threat, owing to his age and infirmities.

“I didn’t want them to be kicking down doors assuming he was this violent, evil threat,” he recalled. “I just didn’t want it to be this whole commando thing.”

A few weeks after Cinquanta first got his tip about Ramon Montoya, the former cop – not an especially patient man – dusted off some of that Callahan swagger and phoned agent Marcum. Cinquanta recalled telling the agent that he and some of his former cop pals were heading to Española.

“You can’t just come down here and kick in his door,” Cinquanta recalled the agent saying. (Marcum and another agent declined through an FBI spokesman to comment for this story.) Cinquanta agreed to stand down as the bureau sought a new warrant to apprehend Pusateri for unlawful flight to avoid prosecution.

BEHIND BARS

Pusateri enjoyed a lovely morning visit from Mario on Aug. 5, 2020. The sun was out and the world was shiny, he would later recall. And when Mario left, he headed for the bedroom.

Mario climbed into his car and drove away, then dialed the FBI agent awaiting his call.

A short time later, Pusateri heard a loud banging on his front door.

“What the hell is that?” he recalled shouting.

Now he saw them, men in tactical gear bursting into his home.

“They got their rifles,” he said. “They got everything out, and (they’re) ready to blast me.”

Agents separated Pusateri from Esther Chacon, the love of his life.

“I was a wreck,” Pusateri recalled. “I just told myself, ‘This is it. They finally got me.’”

Daril Cinquanta shows where he was shot.

But his old instincts kicked in. He denied that he was this Archuleta person, this Pusateri. But agents matched his faded tattoos with decades-old photos and also took his fingerprints.

Game over.

The FBI trumpeted Pusateri’s arrest in a 477-word press release in which Colorado’s top law enforcement officials applauded each other for what the Denver police chief described as their “tireless commitment” to bring him to justice. The case that was decades old, sometimes cold, now solved.

Cinquanta couldn’t help but notice that the release didn’t mention his name or his role in resolving the case. But he and his vivacious wife Chris, the hairstylist he married in 1999, toasted the news anyway as reporters from around the world rang Cinquanta’s phone seeking interviews. He was happy to tell them how he helped to end Pusateri’s run after 45 years, 11 months, and some change.

To this day, Cinquanta says he has not learned the identity of the man who phoned him with the best tip of his life, although he strongly suspects the tipster is connected to his old stable of informants. Perhaps, he said, the tip was repayment for an old favor.

If so, they’re all square.

Pusateri lays his head these days in the infirmary of a state prison on the north side of Denver. But don’t look for him under that name. Corrections officials still list him as Luis R. Archuleta.

“I know it’s not legal,” Pusateri said. “I know I have a Social Security (number) and a birth certificate that says I’m someone else, you know? Not Luis Archuleta. But one day, if I can, I’ll have all that changed.”

Pusateri is closing in on 79 years old and says he has colon cancer and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. He wears a nasal cannula, which sends him oxygen 24/7, but he was sometimes left breathless and hacking during interviews for this story.

Few American fugitives rounded up by the authorities stayed on the run longer than Pusateri. The record holder appears to be Frank Freshwaters of Akron, Ohio, imprisoned for manslaughter after a 1957 auto accident. Freshwaters walked away from a prison farm and stayed on the run 56 years. But Pusateri’s decades as a fugitive, combined with his dramatic escapes and Cinquanta’s never-ending pursuit, puts him in a league of his own.

He expressed disappointment in his son for betraying to federal agents the secret he had confided in him. But as Mario pointed out, he had merely confirmed what the FBI learned from Cinquanta and said he was not the anonymous tipster who phoned the retired cop.

But this was little solace to his dad.

“I’m kinda angry at him,” Pusateri said. “I still love him.”

Pusateri offered some context for his extraordinary run as a fugitive. For one thing, he said, creating aliases back in the 1970s was much easier than it is today because driver’s licenses were made of card paper and easily altered with a typewriter. He lived so long as “Ramon Montoya” that when record keeping went digital, the man he created on paper simply endured.

He stayed out of serious trouble for decades, working honest jobs. Pusateri said he stinted as a short order cook, construction worker, carpet layer, scrap metal collector and yard worker, and for years earned money by slipping advertising inserts into copies of the Rio Grande Sun weekly newspaper.

Two of Pusateri’s children -- Mario and his 39-year-old sister Victoria Cisneros – described him as a smart, loving dad who taught them simple pleasures like fishing and cooking. Mario said he was just a kid when his father was paid a settlement from a construction accident that severely injured his back. His dad bought some property, a horse and a three-wheel ATV that delighted his kids. But he kept his life simple, and under the radar.

“He just lived life to get by,” Cisneros said. “He used his two hands to get by, his mind to get by, his cleverness to get by. And he met my mom, he had us kids, and we are who changed his life.”

Daril Cinquanta

What people fail to see, Cisneros said, is that her father self-rehabilitated on the run. She’s thinking about telling Cinquanta that in a letter, hoping that perhaps he can forgive her father and let go of what she described as the former cop’s obsession and anger. She also believes her dad’s capture came with a benefit.

“Honestly, it’s a weight off his shoulders,” she said. “After all these years, he does not have to live in fear. He does not have to lie anymore. He doesn’t have to pretend anymore.”

Pusateri can still envision that reckless hothead who once shot a cop. He described himself then as a gangster who gave off a just-keep-walking vibe to folks who glanced his way, a look he describes as a shadow.

“The shadow follows me,” he said.

Pusateri proffered his version of the crime that defined both his life and Cinquanta’s: The gun went off entirely by accident and he never meant to shoot anyone. That story has been rejected by judge and jury, and Pusateri still offers no conciliatory words for Cinquanta, whom he described – with a mix of hindsight and conjecture – as a cop who tore people down to build himself up.

The collision of these two men 50 years ago begs a question — Was Cinquanta’s decision to stop and frisk Pusateri a form of harassment or simply prescient police work? He could have driven past that Chevy II, picked up that Rocky Mountain News and gone home. But something told him there was evil in that car.

One day on the phone from prison, Pusateri described the moment he fired that bullet in 1971, Cinquanta laid out on the pavement and him sprinting out of that housing project.

“And there I am running away,” he said. “I went under a house and I stayed down there until it was dark, and all day I could hear dogs and cops walking around and, well, I just didn’t get caught, man. I got away with it. And ever since I just managed to keep on running away and running away.

“So, 40-some years later, here I am again.”