Chasing A Fugitive For 45 years: A Dirty Harry-Era Cop, A Career Criminal And A Quest For Justice

Dec. 13 2021, Published 2:33 p.m. ET

Denver police officer Daril Cinquanta closed out a quiet graveyard shift on the morning of Oct. 3, 1971, with a trip to Winchell’s Donuts, where he picked up a carton of chocolate milk and a couple of glazed twists. On the way home, he drove through the Quigg Newton housing project to snag a copy of the Rocky Mountain News at nearby Sunnyside Drug.

He never made it.

On a tree-lined street in the projects, Cinquanta spied a tough-looking guy accompanied by two women in the front seat of a black Chevy II at the curb. The dark-haired man, wearing a goatee, sunglasses and an olive-colored Fidel Castro cap, stared straight ahead, suspiciously avoiding eye contact.

Something smelled wrong to the 23-year-old cop. He parked behind the Chevy and walked over to the passenger door, where he asked the man for his ID. But his subject offered little more than a few Spanish words as he handed over his wallet.

The billfold held photos of children and a Social Security card in the name of Luis R. Archuleta. Cinquanta plucked the jacket off the man’s lap, squeezed it for signs of a weapon and asked him to step outside. But as Archuleta stood, the officer caught an eerie look from the woman behind the wheel – as if she were about to say something but held her tongue.

Cinquanta walked Archuleta to the back of the car and asked him to put his hands on the trunk for a pat-down.

Archuleta began to comply before suddenly pivoting to one side, sliding across the rear of the car and smoothly pulling a .38-caliber revolver. Cinquanta saw a flash of the chrome barrel and threw a hard punch to Archuleta’s temple, knocking off his shades and cap. He lunged for his assailant’s wrist to get control of the gun. But Archuleta was too quick, too strong and squeezed the trigger.

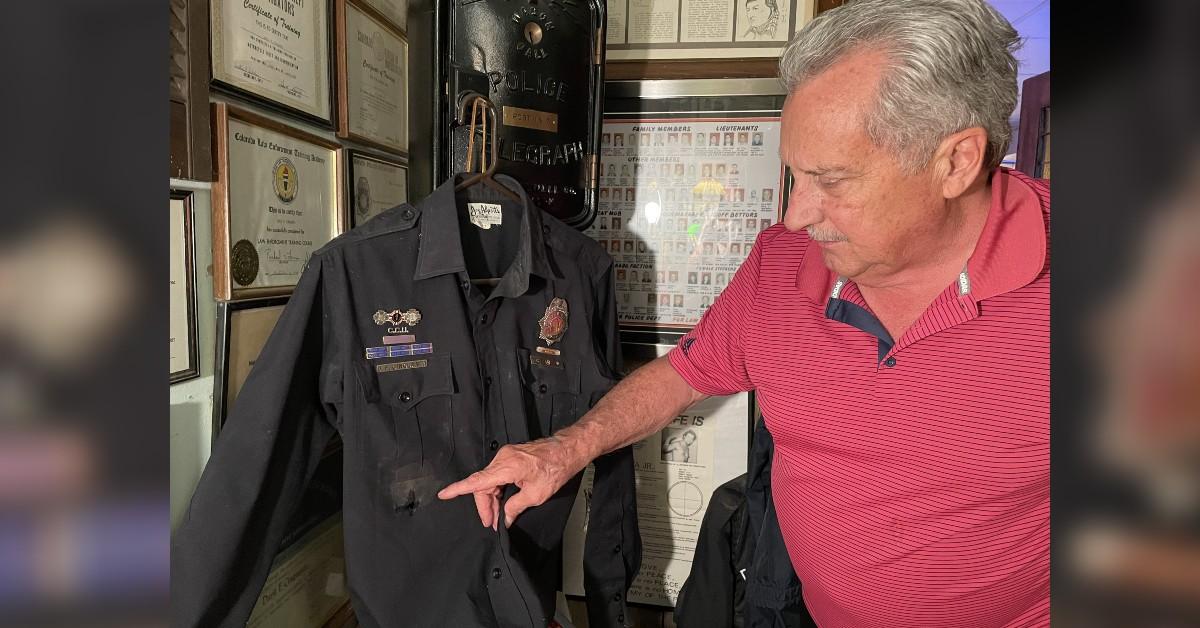

A hot slug drilled through the officer’s chest, clipped the bottom of his right lung, passed through his liver and exited through the back of his uniform shirt. Cinquanta found himself on the ground, uselessly clutching his own .357 Smith & Wesson Combat Magnum.

He lay there for a confused instant sucking air and feeling no pain, his world gone eerily silent as Archuleta sprinted away.

Cinquna tried to stand, but his legs failed to cooperate, so he crawled to his patrol car, leaving a slick of warm blood on the cool street. Cinquanta heaved himself inside the car, grabbed his radio mic and bleated an animal cry for help. Sirens soon filled the neighborhood.

That shooting came at the front end of America’s first major war on drugs, a President Richard Nixon administration campaign that pushed cops and dope peddlers across the nation into daily and often deadly collisions. Indeed, Cinquanta was one of three Denver cops shot in the line of duty in less than 24 hours, one of whom was murdered with his own revolver.

The attack on Cinquanta set in motion one of America’s longest fugitive manhunts, a nearly half-century pursuit — sometimes going cold — abandoned by everyone but Cinquanta himself, a crusty gray-headed retiree too ticked off to let it go. It was a hunt for a man named Archuleta, but that was only an alias. Where was the man behind the name? Cinquanta found his motivation to keep hunting in the shower each morning as he soaped the surgical scar that ran from his sternum to his navel.

The wound offered him a daily pep talk that Cinquanta recently reduced to two words: “Unfinished business.”

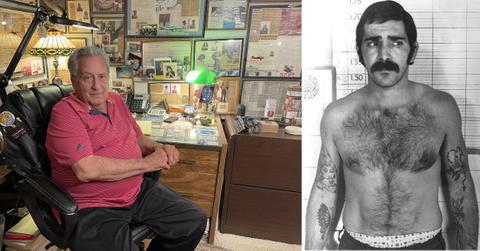

Daril Cinquanta shows a bullet hole

A DIFFERENT AGE OF POLICING

On the day he was shot, Cinquanta’s wallet held the St. Michael prayer card his Italian-American dad had placed in his hand as he left for the police academy in 1970. His dad told him to carry it always as protection against evil.

Maybe it worked. Surgeons at Denver General Hospital miraculously repaired Cinquanta’s fiendishly wounded liver, an operation one doctor later likened to sewing up Jell-O. Meanwhile, police investigators found the cap the officer had knocked off his assailant’s head. It held a pin for the Crusade for Justice, a militant Chicano organization that operated much like the Weather Underground.

There was no sign of the shooter himself.

Cinquanta recovered from his wounds and found himself reassigned to a painfully boring desk job in January 1972, a maddening time for a gung-ho cop to find himself pushing pencils.

“Dirty Harry” had premiered weeks earlier and now showed on movie screens across America. Clint Eastwood starred as Harry Callahan, a maverick detective who routinely trampled the 4th Amendment rights of crooks in his path as he pursued a serial killer. Protesters later decried Harry as a “fascist pig,” but the film was a box-office smash and Cinquanta positively dug Callahan.

Policing was a wildly different business in those days. The Denver Police Department did not equip its officers with body armor or portable radios, there were no body cams or cell phones, and DNA had never solved a crime. Cops like Cinquanta frequently stopped and frisked people with little interference from the Supreme Court. And when it came to the use of deadly force, many officers held to the adage that it’s better to be tried by 12 than carried by six.

Ten months after taking a bullet, Cinquanta returned to street work. Finally free of the desk, he threw himself into it with Callahan swagger, turning himself into an ardent student of crime fighting with big plans.

“All I wanted to do was be a detective,” he said recently.

Cinquanta learned at the knees of hardened veterans of the police force, who coached him to study mugshots. He examined hundreds of them – learning how the perps walked, talked and dressed – so he would know them if he saw them on the street.

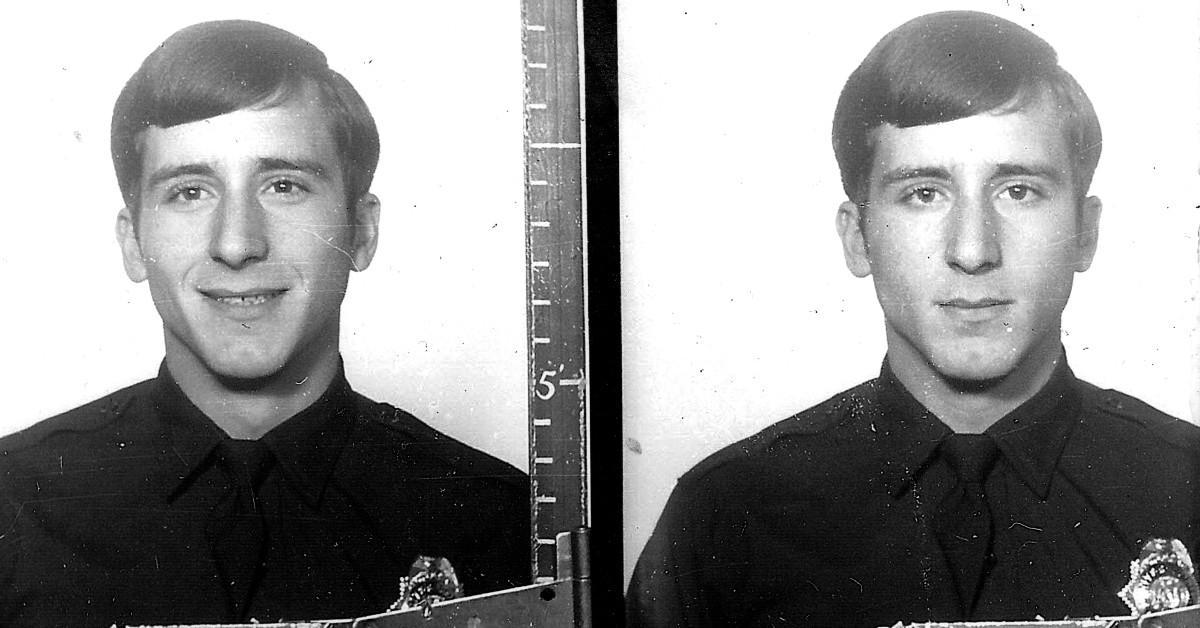

Daril Cinquanta in the police academy

The young officer discovered he had a knack for recruiting informants, mostly Chicanos jammed up on criminal charges and happy to take his get-out-of-jail-free cards. He built a stable of snitches, developed their trust and sometimes dug into his own pocket to buy diapers for their kids. They paid him back with names, most of them Chicano.

Cinquanta busted an impressive number of crooks, chain-smoking Marlboros and often working without pay after his shifts ended. Much of his drive, he would later discover, came from a dark place. He was trying to live down the errors he made on the day he was shot, a scene that played and replayed in his mind.

“I should have backed up and pulled my gun,” he said recently. “It was a stupid rookie mistake, but I was so close to him, you know? What was I thinking?”

AN ESCAPE FROM POLICE

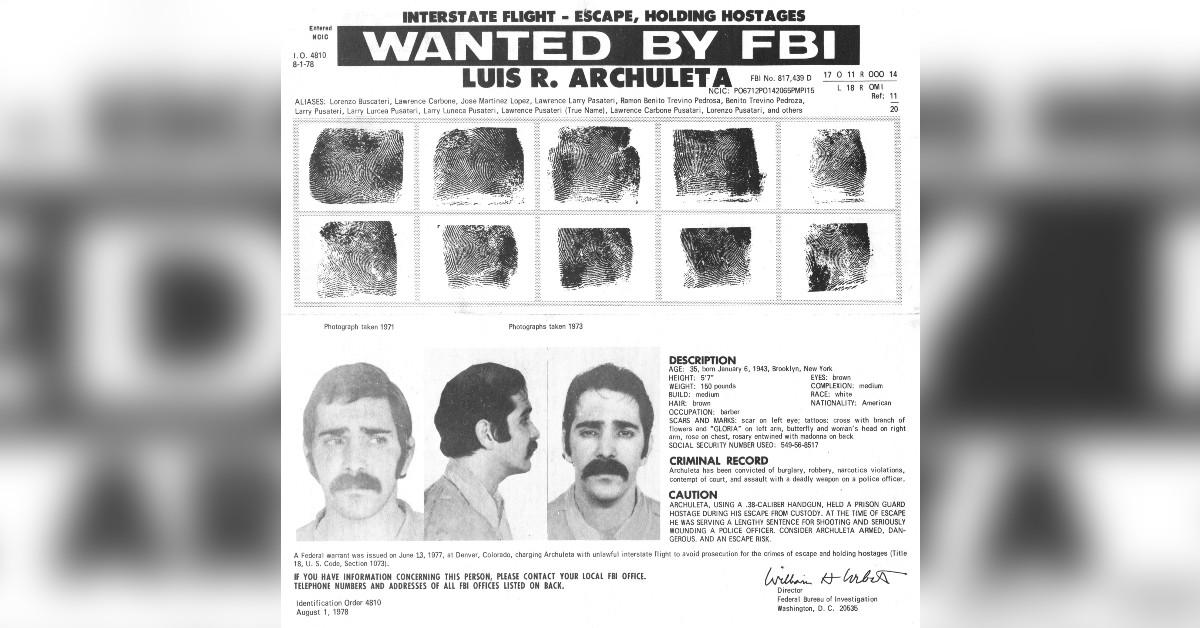

The man who shot Cinquanta was a small-time heroin dealer rounded up in 1972 by police in Mexico after he and a cadre of armed men reportedly got into a shootout with the federales. They first identified him only as “Tingo,” but his fingerprints came back to Lawrence Pusateri.

That was the name the Italian-American was born under in Brooklyn in 1943, but he eventually learned to hate the name during his childhood in East Los Angeles. There he grew up among Chicanos and fully assimilated into their culture.

Mexico turned Pusateri over to Denver police at the Laredo,Texas, border on June 20, 1972, to face charges in the shooting of Cinquanta. Pusateri figured that he was probably headed to prison. But he pointed out in a series of exclusive interviews that he always felt confident he would find a way to escape.

He had done it before.

Six months before the Cinquanta shooting, the State of California sent Pusateri to a prison camp in the Gold Rush town of Vallecito to serve an indeterminate term of up to 15 years for burglary and possession of narcotics.

Pusateri had it good in the camp, fighting wildfires on inmate crews by day and bunking in a low-security lockup at night. But he hated confinement, having given much of his childhood to reform schools.

“I was mad,” Pusateri said, “and I was stupid.”

In the early hours of May 11, 1971, he and a fellow inmate stuffed their beds with pillows and blankets, crept out of the dorm, and ran nearly two miles down a winding road, where an accomplice with a car picked them up at a pre-arranged spot.

A poster looking for Luis Archuleta

Pusateri soon turned up in Denver as “Luis Archuleta,” the alias he was using when he shot Cinquanta. He fell in with the Crusade for Justice, which had given him the “Tingo” nickname. The organization served as a powerful voice for Chicanos as they protested police brutality and pushed for justice reforms in much the way Black Lives Matter would later stand up against racial injustice.

The group informally gave the city’s Columbus Park a new name, “La Raza Park,” although the city waited until 2020 before making it official.

A Denver judge in 1973 sentenced Pusateri to a prison term of between nine-and-a-half and 14 years for his assault on Cinquanta. He soon landed at the Colorado State Penitentiary.

On Aug. 15, 1974, corrections officers shackled Pusateri’s wrists and ankles and loaded him into a white station wagon bound for a state hospital in Pueblo. He had previously complained about a bump on his finger, which he thought a doctor should see. Accompanying him were several other prisoners, including his buddy Sidney Riley.

“He was a crazy little dude,” Pusateri later recalled of Riley, “a happy-go-lucky kind of guy. He had a lot of time to do; he had shot and killed a cab driver. … Talking to him, you wouldn’t have thought he was a bad guy at all. But that’s what he did. We all have a story, you know?”

Once the prisoners reached the hospital waiting room, one of the two corrections officers who accompanied them permitted Riley to use the restroom, before peeling away to make deliveries to inmates in the medical ward. This left 31-year-old corrections officer Stanley Thomas to guard the inmates.

Thomas gave Pusateri permission to use the lavatory. But after hearing him call for help, Thomas hurried to the doorway and found himself staring into the barrel of a .38-caliber snub-nosed revolver, one of two handguns smuggled into the restroom and hidden in a trash can by one of Pusateri’s contacts on the outside.

Pusateri had removed his shackles inside the restroom, having also obtained a key for the restraints, and now ordered Thomas to join him there. As Thomas later pointed out, he complied without a word.

“I’m not arguing with a .38,” he said.

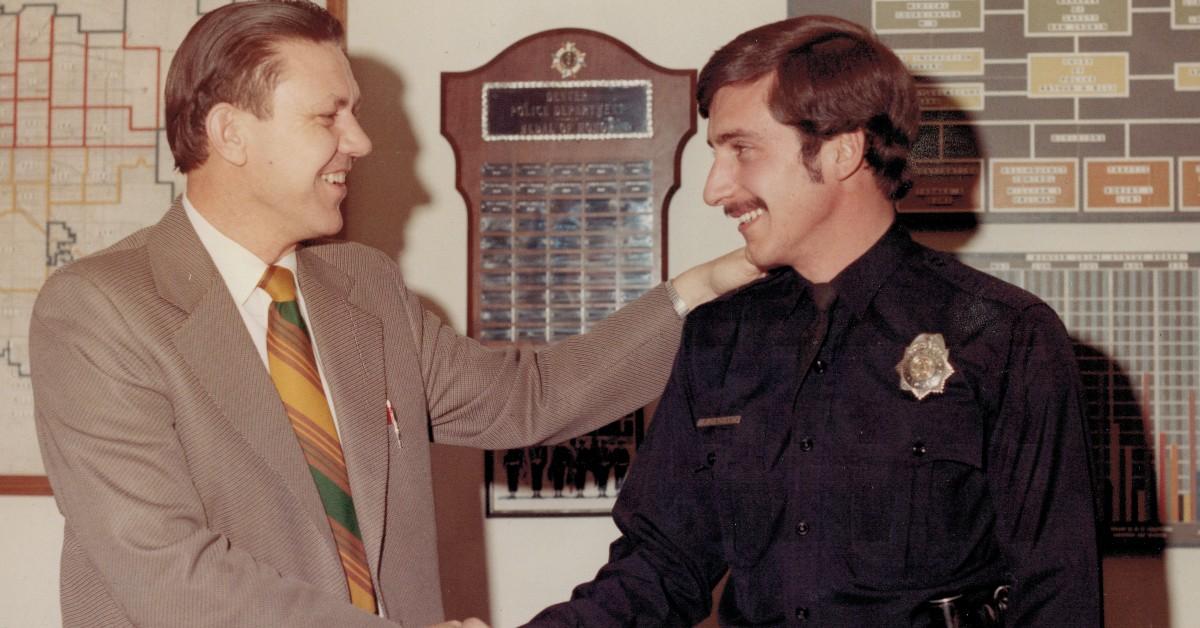

Daril Cinquanta receiving a medal

Pusateri used his wrist irons to shackle Thomas to the frame of the toilet stall, stuffed a prison-issue handkerchief in his mouth and slipped out of the restroom with the revolver tucked in his waistband.

Thomas’s partner, officer Henry Schulze, returning from his trip to the medical ward, spotted Riley moving for the hospital’s front door and confronted him. Riley whipped around and pointed his revolver at the guard, forcing him to walk in front of him. Pusateri then stepped out of an exam room and helped Riley march Schulze to the restroom. They pushed the officer inside and broke into a dead run for the parking lot.

A brown sedan, freshly stolen and conveniently marked with a red tag on the antenna, sat waiting for them. The car was later recovered, but there was no sign of the two inmates.

A Colorado prison official phoned Cinquanta to notify him of Pusateri’s escape, an affront that the officer took personally.

“He owed me nine-and-a half to 14,” he said in a recent interview.

Cinquanta quickly obtained a list of Pusateri’s visitors, unsurprised that some of them were members of the Crusade for Justice. Then, four days after the escape, Denver police caught Riley and returned him to prison.

But Pusateri was nowhere to be found. Vanished while on the lam.

Later that year, a tipster told Cinquanta that Pusateri was living in San Jose, California, and gave him an address. Cinquanta persuaded police there to stop by and see if they could find the fugitive. Police found no signs of Pusateri, but they did show Pusateri’s photo to neighbors, who said the man had moved out a week or so earlier.

Police got it wrong, Pusateri said recently, because he traveled to Denver after his escape from the state hospital and laid low in a safe house.

Then he vanished again.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Check back on Dec. 14 for Part 2 and to see how the decades-long investigation came to an end.